This is Your Brain on Motorcycles

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

AFTER SPENDING A SUNNY AFTERNOON out in our yard yesterday-raking up the leaves I should have raked last fall—I was too tired to make anything but popcorn for dinner, so I made a big batch and kicked back to read for the evening.

Casting about for something deeper and more intellectually stimulating than the usual pile of old motorcycle traders that dominate my “reading,” I sifted down and discovered an actual book-yes, a thing with hardly any pictures-that my sister, Barbara, gave me last Christmas. It was called This is Your Brain on Music: The Science of a Human Obsession by Daniel J. Levitin.

Only right that she should have given me this book. My sister ruined my life in 1956, when I was 8 years old, by letting me listen to her 45-rpm copy of “Hound Dog” by Elvis Presley.

I played it on a record player that looked like a small suitcase and listened to it about 8000 times, mesmerized by the beat and sound, trying to imagine where in the world this atmospheric magic could have come from. Certainly not my small hometown in Wisconsin, where bands with names like The Jolly Drunken Swiss Boys were playing at the Legion Hall.

Thus began a lifetime addiction to rock-n-roll, blues, etc.-or any music without tubas in it...

So naturally I dug into Levitin’s book with anticipation, spurred on by one of the thematic bullet points printed on the back cover: “Why we emotionally attach to the music we listen to as teenagers.”

Hmmm...interesting subject. Maybe if Levitin could explain why I still crank up the radio for the Stones or Mitch Ryder, he could also unravel the mysterious attraction to bikes from my own formative years-if you call this “formed.”

It can’t be an accident, after all, that I now own two modern Triumph Twins that (almost) look like they could have been made while I was in high school, or that I still get all weak in the knees when I go to a swapmeet and stand next to a Honda 305 Scrambler, a Harley Panhead or a Bultaco Metralla. Or that I currently have the hots for another Road King, which is nothing but a modem iteration of the first motorcycle I ever rode upon.

Was I mentally ill, or was this normal? Perhaps the book would tell me.

So, I picked it up and started to read. I won’t attempt to summarize the whole volume, because I could barely understand it, but the gist of it seems to be this: Our brains are rapidly developing during our teen years, filling with new information and forming thousands of new circuits, like a spontaneously selfgenerating wiring harness in a BSA 441 Victor, or-in the case of our more intelligent ffiends-a car with too many seatbelt buzzers and Check Engine lights. This process slows down sometime in our 20s, and we are stuck with a relatively hard-wired set of ideas and preferences. Levitin refers to this framework of personal tastes as your “schema.”

Okay, this makes sense. But it doesn’t explain everything.

For instance, I grew up in the Fifties and Sixties, and hit the Seventies in my early 20s, and I admit to being heavily influenced by the sights and sounds of that era. Yet I’ve never really felt “stuck” there. I like Sixties motorcycles, Triumphs especially, but I’m grateful I don’t have to depend on them for transportation these days. And there have been lots of favorites since then.

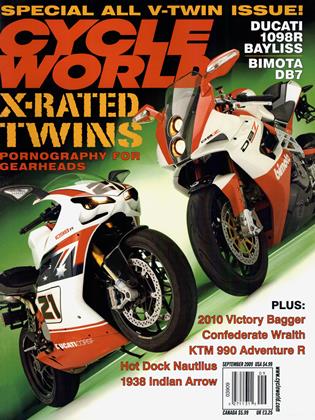

The Ducati 916, for example, a bike to which I was instantly attracted when it came out in 1994. That thing no more resembled my first Honda 160 or Bonneville than the Space Shuttle looks like a Piper Cub. Yet I took one look at the 916 when it was introduced and said, “Oh yes, someday it shall be mine.” By the time I got my money together, it had become a 996, but never mind that. It looked the same.

And then there’s the KTM 950 Adventure. A less likely and more daring set of shapes has seldom appeared on two wheels-there seems to be no styling precedent at all-yet I took an instant liking to the bike and even bought a second one after a friend crashed my first.

I once described my black 950 as looking like a chess knight carved from ebony. I suppose this could have come from watching too many “Paladin” episodes on TV when I was 12. But, re-

gardless of these brain-damaging psychological roots, the shape still looks timeless to me. Flipping back to the other end of the time-space continuum, we also have to ponder the eternal appeal of the Harley Knuckleheads of the Thirties, or the beauty of the Hen derson Fours of the Teens and Twen ties. These are machines made long before I was a gleam in anyone's eye, yet I'd love to own either bike-in a just world, where I was fabulously wealthy.

So I think Levitin was partly right. We obviously do connect with sights and sounds from our own developing years. And yet nearly all of us can easily escape that nostalgic box when the right object appears. Some designs are so good that they easily break through the artificial time barrier constructed by our youthful brains.

Years ago, I was sitting around with a bunch of guys having a deep garagequality discussion on car and motorcycle design, and someone inevitably concluded, “Well, I guess beauty is in the eye of the beholder.”

There was a long silence, and then my buddy John Jaeger said, “No, it isn’t.”

We all looked at him, and he said, “That might be true with people, but I don’t think it is with machines. I don’t think an AMC Pacer ever looked as good as an E-type Jag, and a Ducati Indiana will always be less beautiful than a 750 Super Sport. There are real standards in this world. Some things are just better than others.”

I’d have to say I agree with John, for the most part. When good stuff comes along, it’s just plain good. Doesn’t matter when we grew up.

Although it’s quite clear that Triumphs looked especially excellent when I was in high school... □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Lost Von Dutch

September 2009 By David Edwards -

TDC

TDCOld World Craftsman

September 2009 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2009 -

Roundup

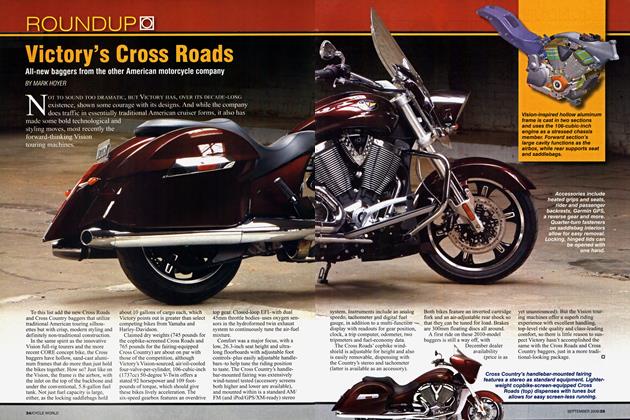

RoundupVictory's Cross Roads

September 2009 By Mark Hoyer -

Roundup

Roundup25 Years Ago September 1984

September 2009 By Blake Conner -

Roundup

RoundupFuzzy Spy Shots!

September 2009 By Blake Conner