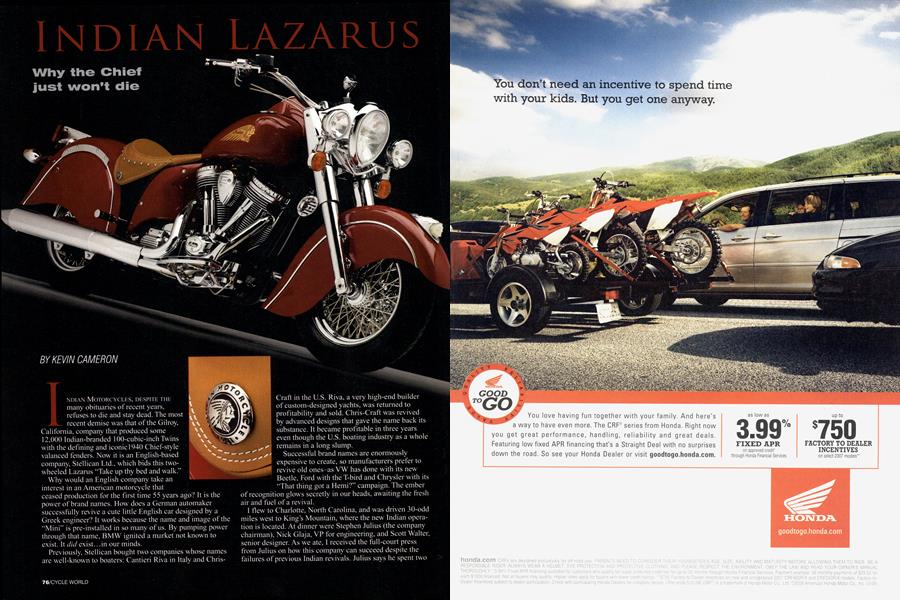

INDIAN LAZARUS

Why the Chief just won't die

KEVIN CAMERON

INDIAN MOTORCYCLES, DESPITE THE many obituaries of recent years, refuses to die and stay dead. The most recent demise was that of the Gilroy, California, company that produced some 12,000 Indian-branded 100-cubic-inch Twins with the defining and iconic 1940 Chief-style valanced fenders. Now it is an English-based company, Stellican Ltd., which bids this two-wheeled Lazarus Take up thy bed and walk."

Why would an English company take an interest in an American motorcycle that ceased production for the first time 55 years ago? It is the power of brand names. How does a German automaker successfully revive a cute little English car designed by a Greek engineer? It works because the name and image of the “Mini” is pre-installed in so many of us. By pumping power through that name, BMW ignited a market not known to exist. It did exist... in our minds.

Previously, Stellican bought tw'o companies whose names are well-known to boaters: Cantieri Riva in Italy and ChrisCraft in the U.S. Riva, a very high-end builder of custom-designed yachts, w'as returned to profitability and sold. Chris-Craft was revived by advanced designs that gave the name back its substance. It became profitable in three years even though the U.S. boating industry as a whole remains in a long slump.

Successful brand names are enormously expensive to create, so manufacturers prefer to revive old ones-as VW has done with its new Beetle, Ford with the T-bird and Chrysler with its “That thing got a Hemi?” campaign. The ember

of recognition glow's secretly in our heads, awaiting the fresh air and fuel of a revival.

I flew to Charlotte, North Carolina, and was driven 30-odd miles west to King’s Mountain, where the new Indian operation is located. At dinner were Stephen Julius (the company chairman), Nick Glaja, VP for engineering, and Scott Walter, senior designer. As we ate, I received the full-court press from Julius on how this company can succeed despite the failures of previous Indian revivals. Julius says he spent two years reading motorcycle business case histories at Harvard Business School (of which he and partner Steve Heese, Indian’s president, are graduates). He was seeking the reasons for failures of motorcycle businesses, both British and American. He knew that operation on borrowed money-the usual way to start enterprises-contained fatal risks. With outside investors, managers must promise to hit certain numbers, and profitability, on a schedule. He saw that ExcelsiorHenderson had “burned through $150 million and built an unnecessary palace of a factory,” while Gilroy “burned through $200 million” and then ceased operations when the principal investor pulled out.

INDIAN LAZARUS

Therefore the central concept of the King’s Mountain enterprise is that it operates on its officers’ own money. I was told there is no debt. There is no plan to operate on a grand scale, so there are no unlikely numbers that must be hit.

The idea is to reach profitability on small production numbers by starting modestly. Bikes will be built by assembly teams-one team of two builds a bike, start-to-finish, just as certain European car engines are built. There is no complex sink-or-swim assembly line that becomes a cement overcoat if production drops below 60 percent of capacity. As was noted in an analysis in The Economist magazine a couple of years ago, automotive startups have in recent times become easier to make successful, not more difficult. This is because such a company can now find experienced specialist suppliers for its parts and subassemblies. These are shipped to a central point for assembly into complete machines. This is a “virtual company,” not a traditional smokestack industry. Another step in the process of understanding this market came with acquisition of 2500 addresses of people who had bought the Gilroy bikes. There were surprises here. A detailed questionnaire was sent to these people, including large spaces in which to write detailed answers. A remarkable 1000 replies-a 40 percent return-was received (in direct

mail such as this, a 5 percent return is normally considered excellent). Of these 1000 owners, 90 percent said they loved their bikes. This indicated that Gilroy, far from having muddied the waters, had actually created loyal customers. And this suggested that resuming production of a further-refined Indian could succeed, under correctly executed management. American employment demographics have changed. Gone are most of the good industrial

jobs that made young men aged 16-24 the core of motorcycling. Manufacturing as a percentage of total employment peaked a long time ago, in 1961. Money has moved upstairs in a rapid concentration of wealth at the top, causing specialist motorcycle brands to aim expensive products at older persons who have money but seek especially interesting ways in which to spend it. This is therefore a luxury-goods business, not simply manufacturing. This has been the real basis of the Riva and Chris-Craft successes-even though the U.S. economy as a whole is down, people at the top have money to spend and a continuing interest in spending it on particularly attractive goods. These are people who have all the “basic kit” of being well-off-multiple houses, in-ground pools, the predictable import autos with

blacked-out windows, Gucci, Armani. Then it gets tough. What if you’re well-off but the basic kit no longer lights your burners? Specialist firms are ready with rare and distinguished treats. Ducati with the 1098R, Chris-Craft with the Roamer 40 Express Cruiser and Indian Motorcycles with a tasteful counterpoint to your executive Harley collection. So goes the argument.

Cycle World's Editor David Edwards has noted that when you glide through busy streets on an Indian, the response from the multitude is many times what it would be for other brands. Brand recognition-and consumer curiosity-remains high for the Indian name and opulent Duesenberg look, even after 55 years.

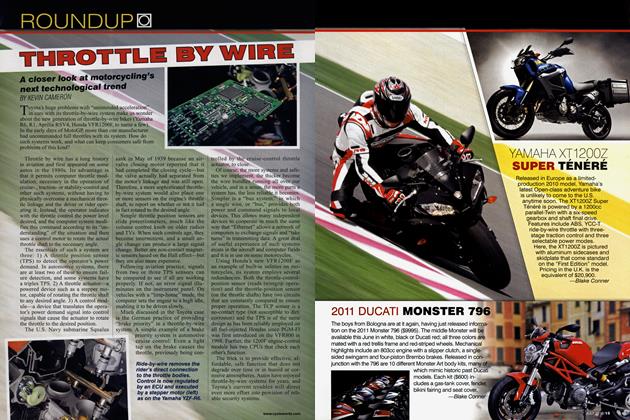

The Indian motorcycle now being prepared for release is a refinement of the Gilroy Chief. Design and validation of that engine were carried out originally by Thunder Heart Performance, Lotus Engineering and VePro, Ltd. Particular points have been changed. Flywheels are now heat-treated to elevated tensile strength to more strongly support the nutsand-tapers crankpin and its fork-and-blade connecting-rod set (Velocette did the very same for its race engines in the 1930s). These new crank assemblies were tested on a threestation cycle of so many seconds at full-throttle/peak power, so many at full-throttle/peak torque, then back to idle for a time and repeat-hour after hour.

In the interest of improved piston cooling, cylinder roundness and long-term sealing, direct-on-aluminum Nikasil bores have replaced the previous iron liners. A slight bore increase brings displacement to 105 cubic inches, or 1720cc.

Mahle three-ring forged pistons are of the boxed, slipperskirt type. The top ring is chromium-plated for wear/temperature resistance, the second ring has a black Parkerized finish, and the two-rail oil scraper is spring-expanded. Cylinder-head alloy and heat-treat have been upgraded.

A single cam with four lobes operates the valves through hydraulic tappets and pushrods. Exhaust valves are critical in air-cooled engines because their temperature can spike very high on summer days towing a trailer up the Rocky Mountains. They are made of Inconel 751, which features “improved rupture strength in the 1600-degree Fahrenheit range.” Good stuff. Combustion-chamber shape is a trench with the two inclined valves within it, its sides filled to form dual squish areas to speed combustion. Faster combustion reduces the time that metal parts are exposed to high temperature. Heads and cylinders are retained by long through-studs.

The single-throttle-body electronic fuel-injection feeds into the expected Y-manifold (located on the left side, a la Indians of yore), and on either side are large lugs which join to a head-steady on the top chassis tube. Exhaust ports in these heads are very short, an important feature in air-cooled engines because so much heat can flow into heads through exhaust port walls.

The extensively shielded stainless exhaust system is on the right. The two headpipes join into the large “torpedo” you see in the photos, which carries a three-way emissionscontrol catalyst in its front section. Each cylinder has its own oxygen sensor, by which the engine ECU can keep overall mixture strength at the “sweet spot” that three-way cat operation requires.

The chassis is massive, a single steel backbone tube boxed for omni-directional stiffness at the steering-head area, splitting below to form a mighty twin-tube base for the separate engine and gearbox. This is a substantial, heavy machine. Final drive is by toothed belt.

Front suspension is a Paioli telescopic fork, rear is a Fox gas-pressurized unit directly attached to a vertical extension of the short swingarm. Arm stiffness is enhanced by formed box sections, welded atop the forward half of each beam.

In order to provide the low seat height demanded by customers of such large machines, the rider’s saddle dips low in front of the rear fender. A seat height of 26 inches was mentioned in this discussion. The classic problem is that of combining such a low seat with enough rear-suspension travel to provide a comfortable ride.

While the Gilroy bike’s fuel tank was in two separate sections, each having to be filled through its own cap, the new tank fills from a single point. The central podium that carries the tank-mounted instruments is now cast-aluminum, replacing what apologists like to call “polymer,” but which we know as plain old plastic.

While I was at the decidedly modest plant (formerly an International Paper Company warehouse, bought very

cheaply), a suspension-test bike was coming and going, downloading its data to a laptop. The rider (one of the 23 who are engineers, out of the present 33 employees) was working on the tough one: achieving good chassis isolation on sharp bumps without losing vertical control over suspension movement. The engineering staff spoke of the need to do all such work themselves rather than farm it out to specialists because only in this way can the necessary knowledge remain the property of the company.

The single front and rear discs, their calipers and master cylinders are from Brembo, the Italian firm that has equipped so many of the most successful roadracing machines of the past 20 years.

As you’d expect, many visual aspects are optional. Textures and colors of leather for the

seat, a variety of creamy paint choices, hard and soft bags. There are Michelin tires for the blackwall look, Metzelers for that 1930s Cary Grant whitewall style.

The production area I was shown was simple and wellilluminated. A fixture holds a completed crank-and-rods assembly, and one case half is slid over it and pulled up against the bearing. The whole build is flipped over, the second case

(provided with sealant from an automated station) slid into place and bolted-up. All of this takes place in a small area.

A completed engine is placed in a pneumatic positioning device so it can be angled and aligned for bolting into a

chassis. The Baker six-speed gearbox bolts to its pads behind the engine.

All these parts come from suppliers.

Although there is a well-equipped R&D machine shop and test-article build area in the building, there are no machining lines here. Parts arrive from suppliers, are inspected and gauged, and await assembly.

The concept behind such small-scale methods is “slow, organic growth,” the idea being to build at a scale that allows profitability at low production numbers. If the machines find an expanding market, production can be scaled up by adding build teams, as the former paper warehouse is roomy. If demand is

steady but modest, Stellican would have what’s known as “a nice little business,” and that would be fine, too.

Selling price will be over $30,000, so durability of function and appearance is essential. Because I could see only basic facilities for testing, I must assume that much of the durability program was undertaken at Gilroy previously and with suppliers now, with the addition and retest of the abovedescribed changes. My guide on the factory tour, General Manager Chris Bernauer, is an engineer with 11 years at Harley-Davidson. He told me that he has the greatest confidence in the engine and gearbox, which is as it should be. This “Bottlecap engine”-so-called because of the distinctive fluting of the edges of its valve covers-has a 45-degree cylinder angle, not coincidentally the same as the Harley Evo motor that was its basis. Purists may carp that original Indians were built with a 42-degree angle, but the smaller the Vee angle the tighter the size limit on piston diameter (their skirts would otherwise clash near bottom center). If the aim were to re-create Indian 100 percent as it was, this Chief could not have modern overhead valves and the high torque and fuel efficiency of high compression. It would be a flathead like the bikes I saw on Colorado highways in the summer of 1963, making a pedestrian 40 hp or less. Few potential buyers would happily accept that.

Much thought has gone into finding suitable dealers. The nation’s markets have been broken down by size and location, and the initial presentation will emphasize the major urban areas. Where possible, dealers will be urged to build a specified building, which will guarantee a “luxurious and agreeable retail experience” for customers. There will be no Indian motorcycles tucked into the corners of auto dealerships; the aim is to create mainly single-brand dealers.

I found myself fascinated by the studiousness of this team’s approach. This is quite different from the public image of businessmen as a group of portly Throckmortons, ponderously adding up

columns of figures on 1930s Gestetner desk calculators. In fact, this approach began to remind me of high-level motor racing, in which preparation and detailed chassis setup constitute what is really a complex, many-dimensional bet-with all the internal excitement and suspense that placing such a bet creates. We can all see such excitement and suspense in race paddocks, but the notion that these things could also drive active minds in business is attractive. When study and practice reveal the correct choices, the machine is rolled to the start line. The days spent with case histories in the B-School library, the analysis of previous owners’ product evaluations and the intense process of building up the operation in King’s Mountain are the analogs of tire choice, suspension settings and fuel-injection scheduling. The “race” begins at the moment these machines go on sale. □