TDC

Tradition updated

Kevin Cameron

WHAT IS THE “RIGHT” ARCHITECTURE FOR a motorcycle engine? At the moment, majority opinion backs the V-Twin and the transverse inline-Four.

Yet many other arrangements have been proven workable. Honda has had a long affair with V-Fours, beginning with the oval-piston NR500 racer and continuing with a flood of VFRs. The potentially very nice feature of a V-Four is that it needs only a little more than half the crankshaft and crankcase weight of an inline. The ultimate in economy of crank and case is the radial engine, which joins as many as nine cylinders—arranged like flower petals—to a single crankpin. Crank and case are no longer than for a Single. Ah, but where would we put all those cylinders on a motorcycle?

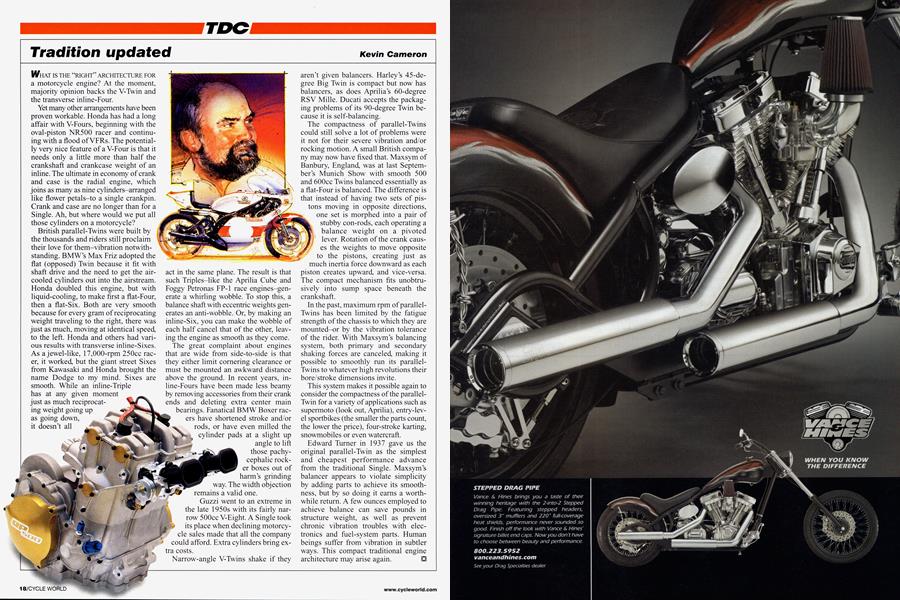

British parallel-Twins were built by the thousands and riders still proclaim their love for them-vibration notwithstanding. BMW’s Max Friz adopted the flat (opposed) Twin because it fit with shaft drive and the need to get the aircooled cylinders out into the airstream. Honda doubled this engine, but with liquid-cooling, to make first a flat-Four, then a flat-Six. Both are very smooth because for every gram of reciprocating weight traveling to the right, there was just as much, moving at identical speed, to the left. Honda and others had various results with transverse inline-Sixes. As a jewel-like, 17,000-rpm 250cc racer, it worked, but the giant street Sixes from Kawasaki and Honda brought the name Dodge to my mind. Sixes are smooth. While an inline-Triple has at any given moment just as much reciprocating weight going up as going down, it doesn’t all] act in the same plane. The result is that such Triples-like the Aprilia Cube and Foggy Petronas FP-1 race engines-generate a whirling wobble. To stop this, a balance shaft with eccentric weights generates an anti-wobble. Or, by making an inline-Six, you can make the wobble of each half cancel that of the other, leaving the engine as smooth as they come.

The great complaint about engines that are wide from side-to-side is that they either limit cornering clearance or must be mounted an awkward distance above the ground. In recent years, inline-Fours have been made less beamy by removing accessories from their crank ends and deleting extra center main bearings. Fanatical BMW Boxer racers have shortened stroke and/or rods, or have even milled the cylinder pads at a slight up angle to lift those pachycephalic rocker boxes out of harm’s grinding way. The width objection remains a valid one.

Guzzi went to an extreme in the late 1950s with its fairly narrow 5()()cc V-Eight. A Single took its place when declining motorcycle sales made that all the company could afford. Extra cylinders bring extra costs.

Narrow-angle V-Twins shake if they aren’t given balancers. Harley’s 45-degree Big Twin is compact but now has balancers, as does Aprilia’s 60-degree RSV Mille. Ducati accepts the packaging problems of its 90-degree Twin because it is self-balancing.

The compactness of parallel-Twins could still solve a lot of problems were it not for their severe vibration and/or rocking motion. A small British company may now have fixed that. Maxsym of Banbury, England, was at last September’s Munich Show with smooth 500 and 600cc Twins balanced essentially as a flat-Four is balanced. The difference is that instead of having two sets of pistons moving in opposite directions, one set is morphed into a pair of stubby con-rods, each operating a balance weight on a pivoted lever. Rotation of the crank causes the weights to move opposite to the pistons, creating just as much inertia force downward as each piston creates upward, and vice-versa. The compact mechanism fits unobtrusively into sump space beneath the crankshaft.

In the past, maximum rpm of parallelTwins has been limited by the fatigue strength of the chassis to which they are mounted-or by the vibration tolerance of the rider. With Maxsym’s balancing system, both primary and secondary shaking forces are canceled, making it possible to smoothly run its parallelTwins to whatever high revolutions their bore/stroke dimensions invite.

This system makes it possible again to consider the compactness of the parallelTwin for a variety of applications such as supermoto (look out, Aprilia), entry-level sportbikes (the smaller the parts count, the lower the price), four-stroke karting, snowmobiles or even watercraft.

Edward Turner in 1937 gave us the original parallel-Twin as the simplest and cheapest performance advance from the traditional Single. Maxsym’s balancer appears to violate simplicity by adding parts to achieve its smoothness, but by so doing it earns a worthwhile return. A few ounces employed to achieve balance can save pounds in structure weight, as well as prevent chronic vibration troubles with electronics and fuel-system parts. Human beings suffer from vibration in subtler ways. This compact traditional engine architecture may arise again. □