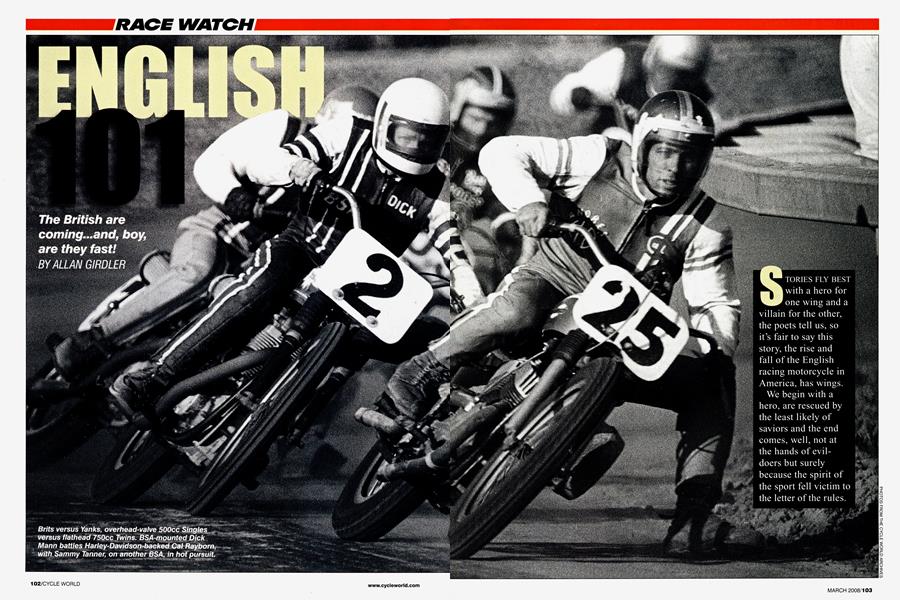

ENGLISH 101

RACE WATCH

The British are coming...and, boy, are they fast!

ALLAN GIRDLER

STORIES FLY BEST with a hero for one wing and a villain for the other, the poets tell us, so it’s fair to say this story, the rise and fall of the English racing motorcycle in America, has wings.

We begin with a hero, are rescued by the least likely of saviors and the end comes, well, not at the hands of evildoers but surely because the spirit of the sport fell victim to the letter of the rules.

Begin with the hero, one Reggie Pink. Born in the Bronx, New York, he was a professional racer, on board-tracks and in hillclimbs, in the Teens and early Twenties. He rode for Reading-Standard and Cleveland and then, for reasons lost to time, he discovered English motorcycles. Pink visited them at home, so to speak, and won a hillclimb there and-emphasize this part-did three fast laps of the Isle of Man TT course.

Keep that in mind. In 1927, Pink became, according to family and museum records, the first importer of English motorcycles to America, representing AJS, Ariel, BSA, Douglas, Norton and Velocette. That was Pink’s first historic and heroic act.

The second came in 1931, at a low and dismal stage of the world’s economies. The Depression was everywhere and the world’s governments were doing all they could to boost exports and ban imports.

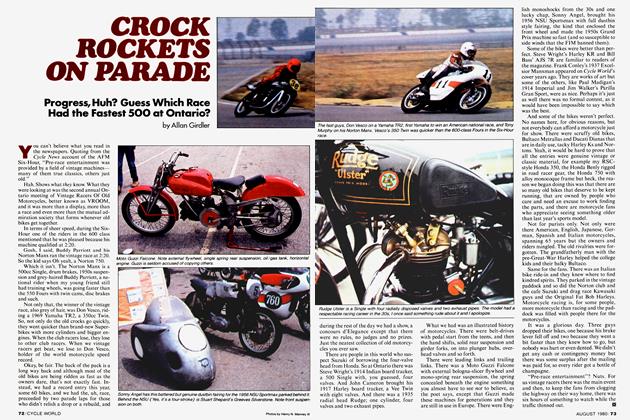

Pink was a member of the local club, the Crotona MC; in fact, the club’s headquarters was at the dealership. Pink knew the most important thing a dealer can offer is something for riders to do with their machines, so one day he and other club guys laid out a course in an apple orchard in Somers, New York. It was up and down, left and right, between the trees, on dirt. On a Sunday afternoon, the club and guests rode to the orchard, raced around the course and rode home. Presumably because the irregular nature of the track reminded Pink of the Isle of Man, he called the event a TT, as in Tourist Trophy.

An AMA official visited Pink’s shop, went to a TT and liked what he saw. So with Pink’s permission, the AMA magazine printed the format and rules of the TT; that’s why this purely American venue, on dirt with turns left and right, plus a hill or a jump if possible, to this day carries an English designation.

Back with history: The Depression nearly killed the sport and the business of motorcycling. There were tariffs and duties and rules. Pink hung on, selling tiny numbers of examples of that large list of imported brands.

In the early 1930s, American national titles were for professional classes, limited only by displacements, as in 21. 30.5,45 or 61 cubic inches-350,

500,750 and lOOOcc.The classes were designated A, for full-race Pros in speedway or flat-track, and B, for larger modifieds in hillclimbs. Note here that in 1931, all the AMA titles worth having went to American machinesHarley, Indian or Excelsior, native sons every one.

The real low point came in 1935. Harley had the only factory racing team, which consisted of one man, Joe Petrali, and Petrali won all the 1935 nationals. Yes, every one, and what fun could that have been? But help was on the way, in the form of Pink’s third heroic act.

In an attempt to make racing affordable and keep riders in the sport, the AMA’s competition committee drafted a new set of rules for what’s technically still known as Class C. Remember the original TT, the Yank version, I mean? You rode your bike there, stripped the road stuff, raced, refitted and rode home. That, in essence, was the new Class C, on stock production motorcycles minus lights and so forth.

And who was a member of the competition committee? Who else? Reggie Pink.

Because this was sport, open to all, the displacement limits were replaced by an equivalency formula. Indian and HarleyDavidson offered sidevalve 750s-the sporting 101 Scout and tuned DL-while the English crowd rode a variety of 500cc overheadvalve models. Thus, by no coincidence at all, Class C was open to 750cc sidevalves and 500cc ohvs-for the same reason modern Superbikes have been 750cc Fours or lOOOcc Twins, and 250cc two-strokes now race with 450cc four-strokes in motocross.

Why this much detail here? Because later critics will say mean ol’ Harley ruled the AMA and the rules were devised to keep the imports out. No sir, that’s what the English call codswallop or horsepucky or worse. To say Reggie Pink voted against his interests, his customers and his sport is to deny the moon landings and even the Holocaust-nonsense. The point here is that the two engine choices were given not to keep people out or give one side an advantage, but to let people in, with a fair shot at winning.

And it worked. Pink was joined by a Velocette importer in 1935, and in 1937 Johnson Motors began selling Ariel and Triumph in Pasadena, California.

The real breakthrough, though, came after World War II. Oh, and let’s forget all that guff about discharged soldiers looking for excitement and how they brought home English sports cars and motorcycles. They weren’t and they didn’t. We’ve been racing since the first two guys on horses met on the trail, and the returning servicemen came home to prosperity. Better still, the G.I. Bill gave them a college education and/or a low-interest home loan, just for the asking.

Prosperity is the key here. We are a flawed species, always looking to stand out or score, to be different. As another motivator, the English economy was nearly destroyed by the war, while English voters ousted the winning team, to be replaced by socialismAusterity for All. “Export or Die” was the charge, which meant that manufacturers who were sending their products overseas could get more and better raw materials. Not only that, the pound sterling was devalued in relation to the dollar, making English bikes and cars real bargains. There were folks here with money to spend, after 15 years in the doldrums, and they spent it.

BSA and Triumph and Norton and Matchless Singles and Twins were lighter and more agile than the Harleys and Indians. And if the English bikes were more trouble, not built for sustained high speeds as the Yankee Twins were, the imports were quicker in the corners.

There was also a social, not to say snob, factor. The Hollywood crowd that drove Duesenbergs pre-war had Jaguar XK120s post-war. The movie stars who sported Harley Knuckleheads in the 1930s replaced them with Triumphs in the Forties and Fifties. Britbikes were cool.

The first import to win a national race was a Norton International ridden by Robert Sparks, a Canadian, in the 1939 100miler at Langhome, Pennsylvania. Another Norton won the Daytona 200, the roadrace at that time, in 1941 and again in 1949.

Perhaps a better way to chart the arrival of the English was that in 1939, the Daytona field was 50 percent Harley, 36 percent Indian and the rest Brits, 14 percent. In 1948, the shares were Harley, 50 percent; Indian, 25 percent; and English, 25 percent. As historian Jerry Hatfield wrote, “Harley was holding its share, but Indian was losing to Norton, BSA and Triumph.”

This brings us to that unlikely benefactor. All the makers had learned a lot doing war work. Harley-Davidson was still a family-held corporation, and the founders’ children knew the public would buy anything in the store, so post-war Harleys were the old designs-sidevalve, rigid rear ends, hand-shift, etc.

Back at the Wigwam, as the Indian guys called the Springfield plant, Indian had been taken over by visionaries, executives with no motorcycle experience but lots of plans. They dropped the sporting Scouts and high-dollar Fours and put all their money into a completely new line: lightweight ohv Singles and Twins in the English mode.

The designs were flawed, the testing minimal, the introduction premature and the result disastrous. Indian went out of production in 1953.

But wait, there’s the bright side.

The executives who wrecked Indian at home had become involved with imports from the U.K., and when the factory shut down, the dealer and distribution networks were ready. So, presto, the Indian Sales Corp. was selling AJS, Douglas, Royal Enfield, Matchless, Norton and Vincent. (Ironically, Reggie Pink had moved on to Harley-Davidsons.)

Bob Hansen was a Pro rider on Indians before the war. After the war, parts became scarce, and he noticed that the BSA Gold Star was a pretty good motorcycle. His reaction was to buy a Goldie and then a G50 Matchless for the roadraces.

Multiply Hansen’s conversion coast to coast. Especially in the west, with Johnson Motors for Triumph and Hap Alzina, who’d been the western distributor for Indian, now doing the same job for BSA. Suddenly you could get small fuel tanks, straight pipes, skidplates, even flattrack frames, for your Norton, Matchless, BSA or Triumph. Racing was back!

Did H-D know the fight was on? Yes. The Big Twins, which had no rivals from home or abroad, kept the hand-shift they’d always had, but Harley introduced the K-model, a unit-construction 750cc sidevalve with foot-shift and hand-clutch and, yes, swingarm rear suspension-just like you-know-who.

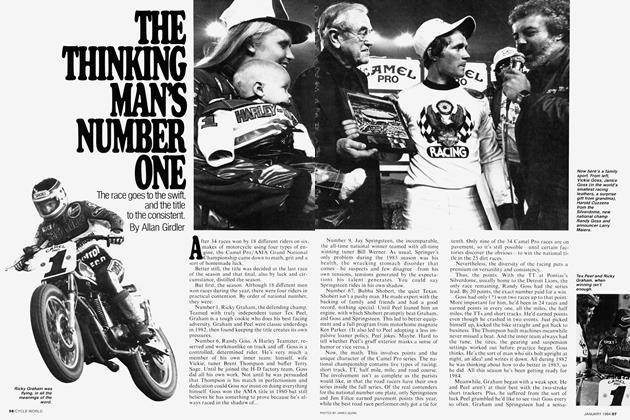

It didn’t work. Not until 1957-when Harley’s ohv XL883 Sportster arriveddid Harley have an answer for the 650cc British Twins when it came to street races. In AMA racing, Harley stayed with the proven sidevalve KR, with increasingly disheartening results. Let’s look at the record:

So much for puppet-master Milwaukee pulling the AMA’s strings, huh? And pay attention to that last column in 1965, a roadrace win courtesy of Dick Mann (say it ain’t so...) on a Yamaha, first GN victory for the Japanese. Within a decade, in 1974, the Japanese wins would total 13 for the year, more than the Yanks and Brits could muster together! In the theater, that’s called foreshadowing.

First, let’s revisit 1968, when the AMA’s rules were revised again. There have been claims that this was a coup, that the English and Japanese importers overpowered dumb old FI-D. Not so. Instead, by 1968 the Gold Stars and G50s, etc., were as quaint and outmoded as the Harley’s Kmodels. The world had moved forward during the 35 years of the AMA’s equivalency formula.

So, the first change was that the big bikes could be 750cc, no limit on valvetrain or even on number of cylinders. The men making the rules had a certain view of the world. They knew about the fights over frames and options, so they required the factories to make 200 examples of each model, to be offered for public sale. This, they reckoned, would guarantee that special racing models would be, in effect, banned, that the playing field would be re-leveled.

Now comes Popper’s Law of Unintended Consequences.

Harley-Davidson didn’t have a horse for the new course. All they could do was de-stroke the TT-class XLR, from 883 to 747cc, and put it in a reworked KR frame with suspension.

Honda wished to make a splash at Daytona in 1970, so management sent three CB750s to an English team and one to Bob Hansen, now tuning, who found a weak spot and fixed it. He also hired Dick Mann, the former AMA champ for whom BSA couldn’t seem to find a ride at Daytona.

Amazingly, the Hansen/Mann Honda won, but Triumph’s Gene Romero took the title that year. In 1971, BSA, having “forgiven” Mann, found him some rides and he won his second national title. Then Harley produced the alloy XR-750, which blew up and broke down early and often. That was soon fixed, Mark Brelsford was Number One in 1972, and the XR rules the roost to this day.

The new rules were working, in other words, but now we come to the end.

Yamaha was new to the sport. It had 250cc two-strokes for short-track, 650cc Twins for the miles, half-miles and TTs, and 350cc Twins for roadracing. The 350s were the weak link. Yamaha wanted the title, so totally per the rules it built 200 TZ700 racers, in effect a pair of 350 twostroke Twins joined crank to crank, and ruled roadracing for the next generation.

Same on the street, as Honda and Kawasaki Fours eclipsed Triumph and BSA Triples.

If the end of an era and an industry can be illustrated by one incident, here one is: Just as the Yank and Brit Twins were losing races to the Japanese in the early 1970s, when I was on the staff of Road & Track and we shared our shops with Cycle World, I borrowed every motorcycle in CWs custody. One day another R&T bike nut and 1 went to lunch on a Honda CB350 and a Triumph Bonneville. We

swapped machines at the burger stand.

When we got back to the office, we wondered, is there anything the Triumph does that the Honda doesn’t do as well, for less money and maintenance? We couldn’t think of a thing.

As the record shows, we weren’t the only ones. □

For additional photography trom “English 101,” visit www.cycleworld.com

View Full Issue

View Full Issue