The English Experience

Baby, won't you ride my bike?

PETER JONES

Americans have tended to perceive British bikes as embodying the whole history and character of the United Kingdom-wonky, wanky and born of the Iron Age. Within every scoot from The Isles is a Celtic heart, hammered from the scabbard of King Arthur. The cigar of Winston Churchill, the ears of Prince Charles, the rings of Ringo, they're in every Britbike.

Because of that, the major complaint about the new Triumphs, by old-school bikers at least, is that they’re too “Japanese.” In translation that means the new bikes are properly designed, engineered and finished. The damn company went and sold out to the needs of consumers, completely ignoring the desires of a few hundred aging Anglophile devotees. Those bastards!

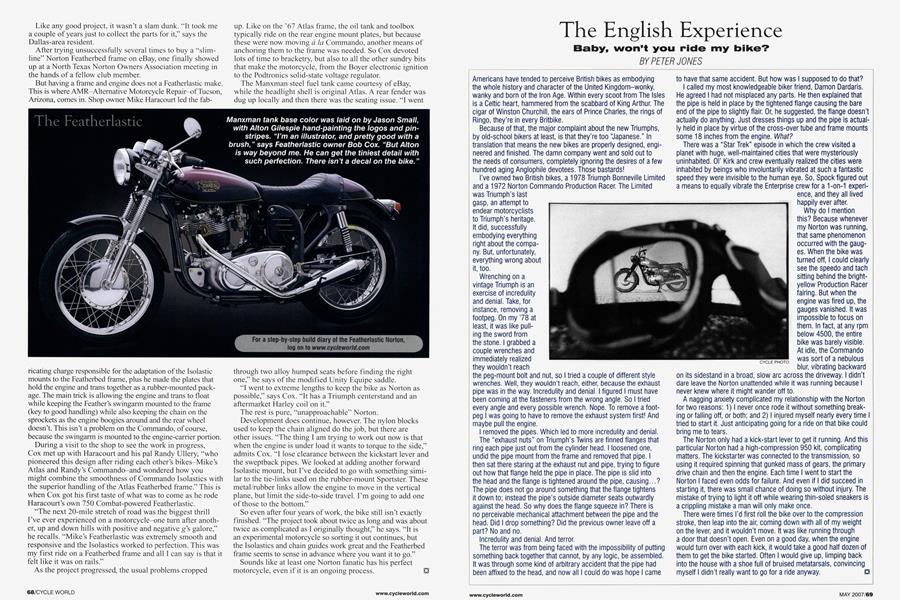

I've owned two British bikes, a 1978 Triumph Bonneville Limite and a 1972 Norton Commando Production Racer. The Limited was Triumph's last aasD.anattemotto

endear motorcyclists to Triumph’s heritage.

It did, successfully embodying everything right about the company. But, unfortunately, everything wrong about it, too.

Wrenching on a vintage Triumph is an exercise of incredulity and denial. Take, for instance, removing a footpeg. On my ’78 at least, it was like pulling the sword from the stone. I grabbed a couple wrenches and immediately realized

they wouldn’t reach the peg-mount bolt and nut, so I tried a couple of different style wrenches. Well, they wouldn’t reach, either, because the exhaust pipe was in the way. Incredulity and denial. I figured I must have been coming at the fasteners from the wrong angle. So I tried every angle and every possible wrench. Nope. To remove a footpeg I was going to have to remove the exhaust system first! And maybe pull the engine.

I removed the pipes. Which led to more incredulity and denial.

The “exhaust nuts” on Triumph’s Twins are finned flanges that ring each pipe just out from the cylinder head. I loosened one, undid the pipe mount from the frame and removed that pipe. I then sat there staring at the exhaust nut and pipe, trying to figure out how that flange held the pipe in place. The pipe is slid into the head and the flange is tightened around the pipe, causing...? The pipe does not go around something that the flange tightens it down to; instead the pipe’s outside diameter seats outwardly against the head. So why does the flange squeeze in? There is no perceivable mechanical attachment between the pipe and the head. Did I drop something? Did the previous owner leave off a part? No and no.

Incredulity and denial. And terror.

The terror was from being faced with the impossibility of putting something back together that cannot, by any logic, be assembled. It was through some kind of arbitrary accident that the pipe had been affixed to the head, and now all I could do was hope I came

to have that same accident. But how was I supposed to do that?

I called my most knowledgeable biker friend, Damon Dardaris. He agreed I had not misplaced any parts. He then explained that the pipe is held in place by the tightened flange causing the bare end of the pipe to slightly flair. Or, he suggested, the flange doesn’t actually do anything. Just dresses things up and the pipe is actually held in place by virtue of the cross-over tube and frame mounts some 18 inches from the engine. What?

There was a “Star Trek” episode in which the crew visited a planet with huge, well-maintained cities that were mysteriously uninhabited. Ol’ Kirk and crew eventually realized the cities were inhabited by beings who involuntarily vibrated at such a fantastic speed they were invisible to the human eye. So, Spock figured out a means to equally vibrate the Enterprise crew for a 1 -on-1 experience, and they all lived

happily ever after.

Why do I mention this? Because whenever my Norton was running, that same phenomenon occurred with the gauges. When the bike was turned off, I could clearly see the speedo and tach sitting behind the brightyellow Production Racer fairing. But when the engine was fired up, the gauges vanished. It was impossible to focus on them. In fact, at any rpm below 4500, the entire bike was barely visible.

At idle, the Commando was sort of a nebulous blur, vibrating backward

on its sidestand in a broad, slow arc across the driveway. I didn’t dare leave the Norton unattended while it was running because I never knew where it might wander off to.

A nagging anxiety complicated my relationship with the Norton for two reasons: 1) I never once rode it without something breaking or falling off, or both; and 2) I injured myself nearly every time I tried to start it. Just anticipating going for a ride on that bike could bring me to tears.

The Norton only had a kick-start lever to get it running. And this particular Norton had a high-compression 950 kit, complicating matters. The kickstarter was connected to the transmission, so using it required spinning that gunked mass of gears, the primary drive chain and then the engine. Each time I went to start the Norton I faced even odds for failure. And even if I did succeed in starting it, there was small chance of doing so without injury. The mistake of trying to light it off while wearing thin-soled sneakers is a crippling mistake a man will only make once.

There were times I’d first roll the bike over to the compression stroke, then leap into the air, coming down with all of my weight on the lever, and it wouldn’t move. It was like running through a door that doesn’t open. Even on a good day, when the engine would turn over with each kick, it would take a good half dozen of them to get the bike started. Often I would give up, limping back into the house with a shoe full of bruised metatarsals, convincing myself I didn’t really want to go for a ride anyway. □