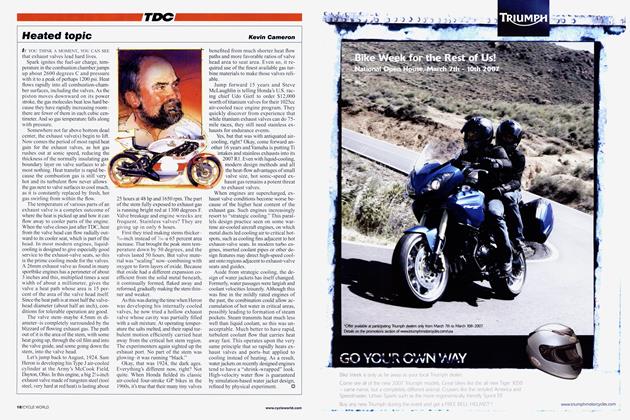

RACE WATCH

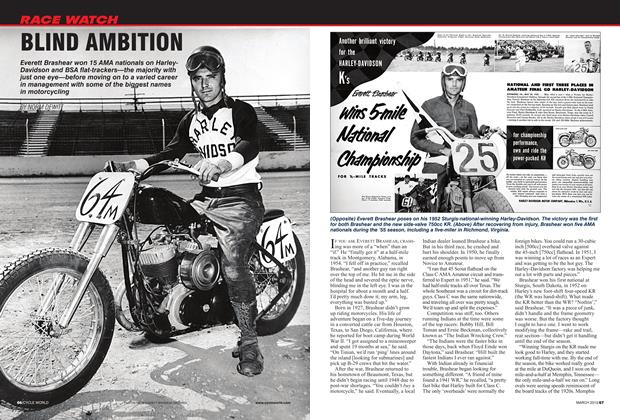

Sonny Angel An American Original

Life and times of an unheralded legend

NORM DEWITT

HE'S NOT A ROCK STAR. NEITHER IS HE THE leader of a motorcycle gang, a builder of high-end custom Harleys or a fictional char acter in an adventure novel. But when you hear a name like Sonny Angel, those are the kinds of images that immediately come to mind.

Truth is, Sonny Angel is a real person, perhaps the most ac complished motorcyclist you've never heard of. He is a true

pioneer of American racing who spent his early days competing in roadraces and chasing land-speed records, and he was the first person to compete on a Yamaha at the Isle of Man. Even today, at age 82, he continues to be in volved with record attempts at Bonneville.

Angel was just 15 when he joined the Navy. He was stationed on an oil tanker in Newfoundland when Pearl Harbor was attacked. On one of his four convoys across the North Atlantic, he found himself all too close to a ship that had been torpedoed and sunk by a German U-boat. In 1951, after seven years in the Navy and 18 months in the Merchant Marine, Angel set off for Europe, his pre-war Triumph Twin in tow.

CONTINUED

In England, he sought out Graham Walker, the great Rudge Grand Prix rider, then editor of the British publication Motor Cycling and the father of Formula One BBC commentator Murray Walker. The elder Walker had a contact list for virtually everyone in the British-dominated motorcycle industry. Angel found a position at Vincent, pending completion of a six-week Continental vacation.

Coordinating his vacation with the 1951 Grand Prix racing season, Angel headed to Spa-Francorchamps for the Belgian GP. Wanting to experience European racing first-hand, he’d come to the right place. This was the Spa of legend, with insanely fast and dangerous tree-lined roads carved from the Ardennes forest leading to and from the Masta straight. Eight miles on the ragged edge of sanity, the track was a daunting introduction to championship motorcycle racing for riders and spectators alike.

Befriending racers Ray Amm and Rod Coleman, Angel joined the gypsy-like GP circus caravanning its way across Europe. Rhodesian Amm was a GP rookie at the time; by 1953, he would be the Norton team leader and achieve a rare sweep of the Junior and Senior TT races at the Isle of Man. Two years later, Amm would lose his life at Imola riding in his first race for MV Agusta. Coleman, from New Zealand, finished fourth the following year in both the 350 and 500cc World Championships. He was one of the few riders to win a GP on the famous AJS “Porcupine.”

“Ray and Rod were very good riders,” Angel recalled. “Amm was more of a risktaker than Coleman; he was fearless.”

In Amm and Coleman, Angel could hardly have found better company. Together, they went to Assen for the Dutch TT, then to Albi for the French round. Along the way, Angel networked, never mind the term had not yet been coined. While in Italy, he visited the factories of the two greatest names of the day in Italian bike racing: MV Agusta and Gilera. Continuing on to Germany, he made contacts at BMW and Horcx. All would eventually play a role back home in California.

Angel returned to Vincent to discover that, because he wasn’t a citizen of England, his salary was limited to just 5 pounds per week-nearly half what he’d originally negotiated. Undeterred, he took the job. Beginning as a bearing fitter, he quickly found himself preparing a Black Lightning for the annual London motorcycle show. However great the rewards of his work, the pay was not sufficient to achieve a reasonable standard of living, and he was forced to leave Vincent-and England. But not before he’d made acquaintances at AJS, Norton, Matchless, BSA and J.A.P.

Accepting a position working as an “oiler” on a tanker ship, Angel quickly reached the rank of 2nd Engineer. Traveling the world, he was occasionally able to attend a major motorcycle race. In 1953, he found himself at the Isle of Man, where in the Senior TT, tragedy claimed GP racing’s inaugural 500cc World Champion, MV Agusta’s Les Graham.

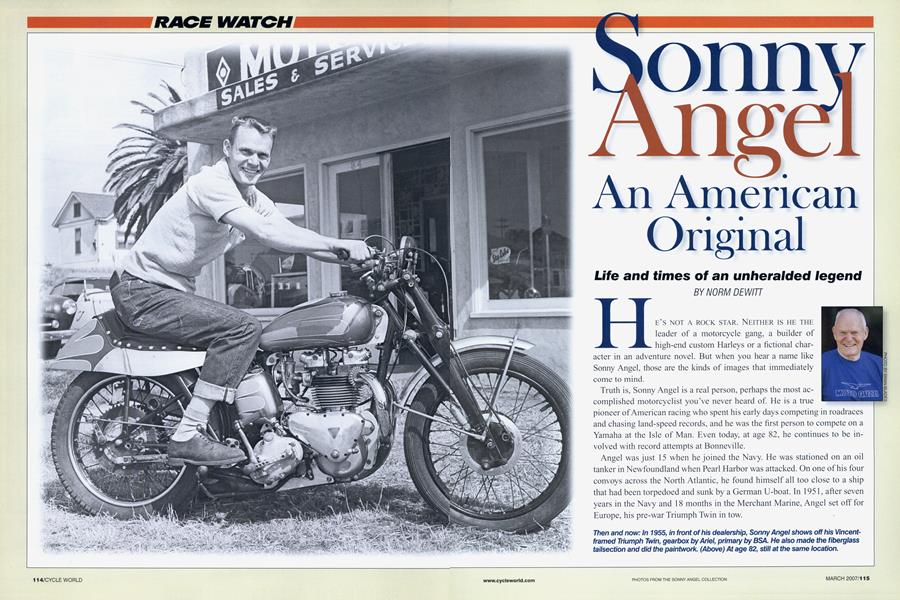

Angel made his mountain-course “debut” on the back of a bike ridden by a one-eyed Englishman. Somehow managing to get through this experience with his body and enthusiasm intact, he would return to the Island seven years later to break new ground for Yamaha, then a TT unknown. The ship’s engineer position paid well, and Angel soon squirreled away enough cash to open a motorcycle repair shopappropriately, Sonny Angel Motorcycles, in National City, California, near San Diego. In 1955, he began to sell new motorcycles, taking on NSU, then Norton, AJS/Matchless and eventually Royal Enfield, Velocette, BMW, Ducati, MV Agusta, Greeves, OSSA, the list goes on.

Free time was filled with racing. The fifth founding member of the American Federation of Motorcyclists, Angel campaigned a 250cc NSU and a 350cc Norton Manx in local drags, at Santa Barbara’s airport race course and Hanford’s banked road course, winning the 350cc class and taking second in the 250cc class. He also scored a second on a 500cc Manx in a one-off event held on public roads encircling the Las Vegas Convention Center.

Along the way, Angel made his first trip to the Bonneville Salt Flats, riding Dave Owen’s 74-cubic-inch Harley-Davidson to a top speed of 110 mph. The following year, realizing that his 1947 Vincent was faster than the Harley, he set a best time of 144.69 mph on the Series B Rapide running 12:1 compression and Amal TT carbs.

Angel also briefly tried flat-track, finishing fourth in his one-and-only appearance at El Cajon Speedway. “It wore me out,” he said, “so I didn’t do that again.”

In 1957, at the inaugural motorcycle roadrace at Riverside Raceway, George Pena, riding Angel’s Norton Manx, won the 500cc class. Angel won the 250cc class on his NSU, and Rene Leonhard won the 175cc class on a Parilia that Angel had sold him. As far as the major classes were concerned, it was a Sonny Angel sweep.

Always the innovator, Angel began to fabricate fiberglass fairings for racing and touring, becoming one of the first fairing manufacturers in the U.S. This experience would prove essential when preparing for his return to the Isle of Man, this time as a rider.

Angel’s IoM adventure began with a 1959 trip to Mexico City. While riding a BMW R60 in Mexico, he sampled a Yamaha 250. This was the first time he had seen the Japanese brand, and it proved far quicker than his BMW. Upon his return to California, he espoused to Motorcyclist magazine editor Bill Bagnail that, “The writing is on the wall-in Japanese characters 10 feet tall.”

Angel contacted Yamaha’s U.S. corporate headquarters, located in a tiny room in a nondescript office building in Los Angeles. In January, 1960, seeing potential in the Japanese bike-maker’s products, he proposed to Yamaha that he race its product in the Lightweight TT at the Isle of Man. The agreement was for Yamaha to provide two racebikes, spare parts and a streetbike (for practicing on the mountain course). Angel would pay transportation costs and any other expenses. At the same time, he became one of Yamaha’s first U.S. dealers.

When Angel saw a picture of the semiscrambler two-strokes Yamaha was sending him, he knew that without extensive modification, the bikes would be completely unsuitable for the TT. On top of that, with the bikes’ late arrival at his shop, he wouldn’t have time to make those changes. So he used a standard YDS2 streetbike he had at his shop as a template to make rearsets, fairings and tailsections for the scramblers.

Testing consisted solely of ripping down nearby Highway 94, where both bikes seized mid-run. When the engines were rebuilt, one was smoother and faster than the other, so that became the primary racebike. Fitted with their homemade fiberglass bodywork, along with a 19-inch front wheel from a Manx Norton, the Yamahas were soon on the way to England-Angel and the racebike by air, the second bike and spare parts by sea.

No engine modifications were completed in time for the two events in England that preceded the TT. The damaged top ends were straight rebuilds for a race at Brands Hatch, but once again, the bike seized during the race, resulting in a DNF. At Silverstone, the bikes suffered predictably similar results. By this time, all the spare pistons had been used up. Angel contacted Hepolite for replacements, but the closest available had domed crowns and were meant for an MV Agusta scooter. He left for the Isle of Man with two non-running motorcycles, no usable pistons, a pile of parts and a lot of work to be done.

Obtaining the machining services of Pelham Chapman in Douglas, Angel set about modifying the cylinder heads to accept the Hepolite pistons. Handmade copper gaskets provided acceptable 10:1 compression. Given what he’d already been through and the strength of the factory competition he was facing, Angel’s chances of success were low.

Prior to his first practice session, Angel had made five laps of the 26-mile course in a van and ridden one lap on the back of a Triumph T110 piloted by GP standout Tommy Robb. Eager for more track time, Angel was one of the first to arrive for official practice, but he was forced to return to his hotel to pick up the required paperwork. He returned to find that his bike had been pushed out of the line. Carlo Ubbiali, one of the dominant riders in the class, was near the front of the line and sent his mechanic back to ask Angel if he’d had any practice. When Ubbiali realized Angel’s situation, he arranged for the American’s Yamaha to be moved up to second in the practice line. This kind gesture enabled Angel to follow bikes throughout the three-lap session to gain much-needed experience.

On the last lap of practice, the bike was running well-until another piston failure occurred at Quarry Bends. A small pin inserted to key the ring gap into position between the cylinder-wall ports had failed, taking the piston skirt with it. Angel had also entered the bike in the French and the Dutch GPs, but with his spares supply exhausted, his European adventure was over. Today, he still has the piston with the pin that didn’t break.

Asked years later about Angel's effort, Robb beamed, “You know, Sonny was the first to ride a Yamaha at the Isle of Man TT.”

Back in California, Angel continued to race. At Willow Springs Raceway, he followed home the great Mike Hailwood and AÍ Krupa, all three on 500cc Manx Nortons. In 1962 and ’63, his 250cc NSU held the track record at Willow. Angel desperately wanted NSU’s Sportmax racing model, but he got caught up in rival AMA/AFM politics.

“The American NSU distributor was Earl Flanders,” said Angel. “I told him, ‘Let me buy a Sportmax. I’ll win races on it, and we’ll sell motorcycles.’ But Flanders was an AMA guy, and he didn’t want me to run a Sportmax in AFM races.”

Out of desperation, Angel contacted the German factory, which found a bike for him in Argentina and shipped it to the U.S. At Willow, revving the engine 1200 rpm past redline, he blew it up in an attempt to outrun Norris Rancourt on the “Gadget,” Orin Hall’s famous Parilia. It was all part of the fun.

In 1967, Angel approached Norton’s American headquarters in Los Angeles with the idea of a four-cylinder bike. “I went to them and said, ‘Hey, you need to build a four-cylinder motorcycle like an MV or a Gilera, four cylinders across the frame with a five-speed gearbox and good brakes,”’ he said. “Their response was, ‘Well, we can’t do that.’ So I said, ‘I’ll be back in a month.’”

Angel built a prototype by stuffing a liquid-cooled, 900cc Hillman four-cylinder car engine into a Norton Featherbed frame. The end result looked like a cross between a Norton Atlas and a hotrodded Münch Mammut. With 60 horsepower at the rear wheel and a weight of 455 pounds, Angel’s creation was the ultimate road-burner of its day.

“It took me three months, not a month,” Angel recalled, “but I ran it in Mexico300 miles at 80 mph.”

Angel took his creation back to Norton. “It was lovely,” he said. “It was just for their benefit that I made the thing, but they weren’t very receptive. They rode it around the block and said they weren’t interested.”

A couple of years ago at the USGP at Laguna Seca, Angel bumped into the former head honcho at Norton. The conversation went as follows:

“How come you guys didn’t accept that thing?”

“Well, the engine was a little ugly.” “Man, it was a car engine! I put the thing in there to show you that it worked. Tell the engine manufacturer to put some fins on it; I was just proving a point. I used all Norton parts-clutch, carburetor, gearbox-stuff you were already making.” With the 1968 debut of the four-cylinder Honda CB750, everyone began a frantic game of catch-up. Angel’s Norton Four never saw production. Today, it serves as an exhibit in his showroom.

“It was five years before another large company made a four-cylinder motorcycle,” Angel said. “Norton would have had a head start with a larger-displacement engine than the Honda.”

Angel spent the next three decades operating his dealership and developing and marketing motorcycle accessories. Some of his more popular creations were the single-carb manifold for Norton Twins and a glass cover for the bevel gears on older Ducati Twins. Growth of the business enabled him to expand his showroom in 1975.

Proving that age is merely a number, Angel returned to Bonneville in 1981 with his #50 Vincent Rapide and rode it faster than he had in 1955, turning a best time of 144.95 mph. To date, he has been to Bonneville 10 times and made 49 runs against the clock.

More recently, Angel and his brother Don have been involved with Max Lambky’s supercharged, twin-engine Vincent streamliner. Pilot Don Angel got the ’liner up to 212.860 mph in 2005.

Angel has no plans to slow down or kick back and spend the rest of his life in a rocking chair. After 53 years, his dealership, Sonny Angel Motorcycles, remains at its original location, where he and brother Don still work every day. It’s a brick-walled, understated, old-fashioned shop where customers are welcomed and people meet on Saturday mornings for coffee, homemade cookies and lie-swapping amongst Angel’s many racebikes and innovative products on display. It’s an interesting, little-known slice of motorcycling history.

Just like its owner. □

For additional photography of Sonny Angel, visit www.cycleworld.com