Looking for Lindbergh

PETER EGAN

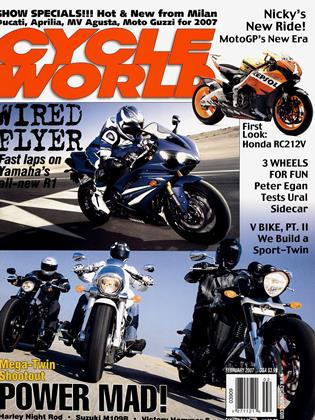

In 1920, motorcycle buff and future aviation hero Charles Lindbergh rode his Excelsior V-Twin from his home in Little Falls, Minnesota, to the University of Wisconsin in Madison. Return with us now—by Ural sidecar rig—to those same country roads. SEE ANYTHING INTERESTING AT THE CHICAGO bike show?” Editor Edwards asked me last winter. “Well,” I admitted, “once again, I spent half my time hanging around the Ural sidecar display. You just look at those things and you want to be on a cross-country trip somewhere, motoring along the backroads of America.” “Yes, they’re very cool,” David agreed. “There’s a lot of interest in the Urals,” I said, “but everybody wants to know if they’re reliable. The guy at the Ural booth said they’ve drastically improved since the company was privatized a couple of years ago. They have Brembo brakes and modern electrics now. But you still have to wonder about a Russian product, especially when it’s essentially an Like me, she’s a pilot and vintage aviation buff, and we have a whole shelf of Lindbergh books in our library. Back in 1987, we spent six weeks circumnavigating the U.S. in our very slow and archaic 1945 Piper J-3 Cub. We flew over Cape Canaveral, landed at Kitty Hawk and got to the Oshkosh Fly-In but never made the detour north to Little Falls. We just ran out of time. But now we had some. Escaping the clamor of suburban Milwaukee, I dissolved into the backroads toward Madison and the ride was uneventful. And fun. The 750 Boxer engine, rated at 45 horsepower, is smooth and civilized, thrumming along happily at 50 mph. It idles nicely at stops, pulls away with broad, torquey ease and light, normal clutch action. That front Brembo brake hauls the bike down right now. It stops straight, hard and predictably, especially with a little bit of rear brake. It tracks straight and effortlessly over the landscape. Everything feels modern, smooth and surprisingly refined-except for that clunky transmission. We cruised through small farm towns on county alphabet roads, stopping for fuel at mid-morning. The five-gallon Ural tank went on reserve somewhere between 110 and 120 miles, and averaged right around 28 mpg on most of our fillups. Not spectacular mileage, but then there’s a lot of weight (736 pounds dry) and frontal area here. Stopping to look at Taliesen, the architectural school founded by Frank Lloyd Wright (another famous UW dropout), I was quickly reminded of one of the great sidecar joys: Easy parking. I was also pleased that the ride quality was so good, both on the bike and sidecar. Spring and shock rates seem perfectly worked out to handle hard bumps and undulations in the road, and Barb said the sidecar seat was comfortable and roomy. Her only complaints were a moderate amount of turbulence around the sides of the windshield and a closer-thanusual acquaintance with clicking tappets and whirring gears. We crossed back over to LaCrosse, where Barb was born, and motored north on Highway 35, stopping at the little river town of Trempealeau. We got a room at one of our favorite places, the old Trempealeau Hotel, which has a four-star (but inexpensive) restaurant downstairs and clean, simple $35 rooms upstairs, where you share a bathroom down the hall. It’s the kind of place Lindbergh might have stayed. Young Charles was an avid outdoorsman, as well as a natural mechanic who was allowed to drive the family Model T when he was 11. He also drove his mother and uncle to California in a Saxon Six touring car when he was 14. Police in Los Angeles ticketed him for driving underage, when he’d just navigated 2300 miles of the worst roads in America. This offended young Lindbergh’s always-powerful sense of logic. He ignored the ticket and drove everyone back to Minnesota, in the age before computers and reciprocity. We pulled up in front of the Lindbergh farm and paid $7 For more on Peter Egan's Ural trip, go to www.cycleworld.com I observed. Just then, a horse-drawn buggy clopped by with surprising swiftness, and another team of horses pulled a hay rake into the farmyard. I narrowed my eyes and thought about the $3.26 we’d just paid for a gallon of premium unleaded. A wind-driven water pump creaked in the breeze.

CW FEATURE

updated copy of a WWII BMW.”

“Maybe you and Barb should take one on a road trip next summer and find out how it works,” David suggested.

Everyone has a favorite sentence in the English language, and that’s mine.

So I immediately called Ural’s U.S. headquarters in Seattle and talked to a very nice woman named Madina Merzhoyeva, who assured me they could provide a Ural Patrol-their bestselling model-for testing when summer arrived.

All set, then. But where to go?

Barb suggested picking up the Ural in Seattle and riding to Alaska, but my friend Mike Mosiman, who owns a Ural in Colorado, nixed that idea.

“The Ural will go 65 mph but it’s a lot happier at 55. If you drive to Alaska, you’ll be looking at truck radiators in your mirrors all day long. Take a trip on scenic backroads with light traffic. That’s what the Ural was made for.” Out came the maps, and I was soon reminded that some of the most scenic-and quietest-country roads in America started right at our front door in southern Wisconsin and meandered northwest toward Minnesota. Red barns, dairy cattle, small towns, ridges and hills, winding roads with nothing on them but hay wagons, horse-drawn Amish buggies and farmers in old pickup trucks. The world as it used to be, when sidecars were real transportation.

“Let’s go up the Mississippi Valley,” I said to Barb.

“Where to?”

“Right here,” I said, stabbing the map with my finger. “Little Falls, Minnesota. Hometown of Charles Lindbergh.”

Barb looked at the map and nodded approvingly.

Lindbergh, often named by historians as “the most famous American of the 20th Century,” is best known for making the first non-stop solo flight from New York to Paris in 1927 at the age of 25.

Less known, however, is his enthusiasm for motorcycling. In 1920, he rode his 1918 Excelsior V-Twin from Little Falls 350 miles down to the University of Wisconsin, in Madison. As an Army ROTC candidate, he also rode his bike to Camp Knox, Kentucky, for summer training, and afterward took a 19-day road trip to Florida and back to Madison, arriving home “with a motorcycle badly in need of repair and nine dollars in my pocket.”

One can only imagine what these roads were like in the early Twenties. Lindbergh eventually dropped out of college in the middle of his sophomore year with failing grades. He confessed that all he really wanted to do was shoot on the rifle and pistol team and ride around on his Excelsior. That March he rode his bike out to Lincoln, Nebraska, to take flying lessons. Good decision. He later bought himself a WWIsurplus Curtiss JN-4 “Jenny” biplane for $500 and went barnstorming all over the U.S.

“We could retrace Lindbergh’s ride to Madison,” I suggested to Barb. “It’s the perfect trip for this bike. The Ural almost looks like it belongs in the Twenties.”

So on an August morning I drove to Steve’s Service Center in the Milwaukee suburb of New Berlin (since moved to Phillips, Wisconsin) to pick up a new Ural Patrol. The Woodland-Green Patrol, priced at $9795, is one of Ural’s pair of two-wheel drive models, along with the more military-styled Gear Up version. They also make three onewheel-drive rigs, the cheapest being the Tourist, at $8595.

The Patrol looked very jaunty sitting there in the shade of a tree: flawless green paint and deep chrome, nice polished valve covers on its ohv Boxer heads. Much evolved from its flathead ancestors in WWII, the Ural now sports a Denso alternator, Ducati-style Italian switchgear from Domino and an automotive-grade American wiring harness with modern blade fuses and connectors. It had 500 break-in kilometers on the odo, with the valves adjusted and fluids changed, ready to go.

Shop owner Steve Krings, a certified sidecar instructor, took the time to give me a few pointers. I’d driven (not ridden, sidecar buffs tell me) a Harley sidecar rig 1200 miles through Baja a few years ago, but sidehacks are so oddly different from motorcycles, there’s no such thing as too much helpful advice.

“Pull out the choke knobs on both Keihin carburetors,” he said, “hit the starter button and go. Push the chokes back in after about a four-minute warm-up. Push down on this little chrome lever beside your right boot for neutral and reverse. The lever behind that engages two-wheel-drive, but don’t ever use it on pavement. There’s no differential, so unless you’re on a loose surface like snow or mud, you can’t turn.” I took a short test ride with poor Steve in the sidecar, and in my first right-hander nearly ran his wheel over a curb. “You sit over the road as if you were driving a car,” he reminded me, “and give the sidecar plenty of room in corners. It has width.

“If a right corner tightens up on you, apply some front brake but keep the power on. Always lean your weight to the inside of a corner, in either direction. And always carry your passenger in the car, never on the rear seat of the motorcycle. You need to keep a low center of gravity.”

I’d forgotten how reluctant a sidecar is to turn at low speed,

and how odd it feels to have your bike lean slightly outward in a right-hand turn. Unnerving at first, but after 15 or 20 minutes you adapt. I remarked that the four-speed transmission felt stiff and notchy. “It takes about 2000 miles for these transmissions to break in,” he said.

Steve stepped out of the car, shook hands and wished me good luck. “Keep it under 50 mph for the first 1000 kilometers to break the engine in properly,” he said. “After that, you can cruise above 60.”

Barb and I loaded the bike that evening. The roomy sidecar trunk easily swallowed Barb’s duffel bag, the Ural factory toolkit and a tonneau cover for the car. My duffel went across the back seat of the bike. And to the top rack we bungeed our old khaki Duluth bag full of raingear, survivor of many Canadian canoe trips. It was the only luggage we had that looked right on the Ural.

In keeping with the vintage/aviation theme, we decided to leave our modern riding gear home and take our A-2 flying jackets. Open-face helmets seemed right, too. With my sidecar skills, I drew the line at leather flying helmets and goggles. It’s one thing to tempt Fate, and another thing entirely to spill its drink and step on its blue suede shoes.

We left early on a beautiful August morning, our first cool, clear day after almost a month of oppressive heat.

On the backroads, cruising at 50 mph-or 35 mph on long, steep climbs-we quickly discovered that there’s an entire American subculture of drivers, mostly polite older people in modestly priced sedans, who have probably never passed another licensed vehicle in their lives and absolutely don’t know what to do when presented with the opportunity. So they follow you forever, even when the road is wide open. Eventually you have to pull over and wave them past.

Or maybe they just like following sidecars and watching them. I would.

You just pull off the road anywhere, hit the kill switch with the bike in gear, turn the key and step off the bike. No looking for a level spot or firm soil for your sidestand, no searching for a flat rock or wondering if the wind will blow your bike over. You just stop. The Ural is also good at U-turns. Stop, crank the handlebars and do a hassle-free, perfectly balanced 180. Park, get off. Never on any trip have I been so willing to turn around and go back to look at something we’d missed. It’s a new kind of freedom.

The noise made conversations nearly impossible. We spent a lot of time shouting “ WHAT?” at each other, and the answer was always unintelligible. Our hand signals became more refined.

My own riding position was ideal: great seat, well-placed handlebar and roomy footpeg position. I haven’t been this comfortable on a bike since 1980, when Suzuki GS 1000s and Kawasaki KZ 1000s ruled the world and seats were not tilted downhill or sculpted to look like the mark of Zorro.

Another nice advantage of sidecars is Fearless Traction. When you barrel around a blind corner and find loose gravel, sand or manure on the road, there’s no cold sweat or panic. On the Ural you just grin and motor through it. Unless, of course, you’re going too fast in an off-camber, decreasing radius downhill corner. That will get your attention, and not in a good way. “Enter slowly, accelerate out,” was Steve’s well-considered advice.

Late in the afternoon, we descended into LaCrosse and crossed the Mississippi into the hills near La Crescent, Minnesota, where Barb’s parents are buried in a lovely cemetery overlooking the valley. Her dad’s grave was flying a veteran’s flag. As Lieutenant Fred Rumsey of the 2nd Infantry Division, he landed on Omaha Beach on D-Day, fought the hedgerow battles of France and survived against all odds to liberate a concentration camp deep in Germany. He told me he rode in Harley sidecars and flew in Piper L-4 Cubs as a forward observer. Fred would have loved the Ural.

In 1920, it never would have occurred to most Americans that you would replicate your plumbing system, over and over again, for every hotel room. It’s only our modern refusal to share that keeps the consumer economy thriving. That, and a growing population. At the time of Lindbergh’s trip, the U.S. population was 106 million. It’s about three times that right now, but you don’t see much change on the backroads around Trempealeau. Time almost stands still.

That night we had our windows open and about every hour a Burlington Railroad train blasted by in a shock wave of noise and clatter, heading up or down the Mississippi. Some people don’t like railroad noise, but I’ll take all I can get. I grew up in a railroad town, so for me it’s the romantic echo of prosperity and travel to far off places.

We followed the river north in the morning and detoured \ inland at Pepin to see the childhood home of author Laura j Ingalls Wilder, a favorite of Barb’s, then crossed the river bridge into Red Wing, Minnesota, famous for its Red Wing Boots and Red Wing Pottery. I bought boots and Barb bought pottery, and all this loot fit easily into our % trunk. Then we cruised up to Stillwater, Minnesota, to visit our old friends Bruce and Linda Livermore.

Bruce is a mechanical engineer who, like Lindbergh and yours truly, dropped out of the University of Wisconsin to “try other things.” I tried Vietnam and Bruce worked as a car mechanic. Years later, we both returned to UW and finished school. Lindbergh didn’t, of course, and you can see how a lack of diploma held back his career.

Interestingly, Bruce’s grandfather, Professor Joseph D. Livermore, was Lindbergh’s advisor in Mechanical Engineering at the University of Wisconsin in 1920.

As we came into Stillwater, I heard a cyclical groaning sound and felt a vibration from somewhere within the sidecar rig or motorcycle. Bruce and I jacked it up at his house and spun the wheels to check the bearings, but couldn’t find anything wrong. A small amount of gear oil was misting out from the rear drive unit around the brake drum and spokes, but no other problems were evident.

We continued on the next day and the noise gradually went away. Transmission break-in pangs, perhaps?

We paused in the little village of Mahtomedi, Minnesota, my own birthplace (yes, there are a lot of birthplaces in this story; too many, some would say), and then zig-zagged north into Minnesota farm country. Past cat-tail marshes, redwing blackbirds and flat farm fields, we ran on geometrically square Minnesota roads all afternoon, then slowed for the “Welcome to Little Falls” sign.

Little Falls is a pretty little place of about 8000 that has a nice old downtown and straddles the Mississippi at the falls— which are now a dam. It’s one of those just-right-sized cities where everything is built on a humane scale and easy to find-hospital, school, working movie theater, restaurants-all with light traffic and easy parking.

The old Lindbergh farm is just south of town on the west bank of the river. Lindbergh’s father was a successful lawyer, farmer, land agent and congressman, and his mother was a high-school chemistry teacher.

A few years later, in 1918, he bought his Excelsior from Martin Engstrom’s Hardware in Little Falls. In photos, it looks like a Model 17-3E, a 998cc V-Twin with a threespeed transmission. In 1918, Excelsior was one of the “Big Three,” third in sales after Harley and Indian, and it was considered a very advanced and roadworthy bike, with a reputation for setting cross-country speed records. Excelsior bought Henderson in 1917, adding the luxurious Henderson Four to its showrooms.

In an odd personal footnote here, when I was 15,1 traded my go-kart for a 1917 Henderson engine to use in a Pietenpol Air Camper, a homebuilt airplane for which I’d acquired plans. I ran out of money after building the wing and sold the Henderson Four to Mr. Neumann, my shop teacher, for $40 so I could afford to go to the prom.

It’s deals like this that have kept me from becoming a household name in aviation.

each to go through the excellent museum and take a tour of the nearby house. In the museum we found a large photo of Lindbergh on his bike and an exhibit of his motorcycle memorabilia, including his wood chest of tools and spare parts, and both his Minnesota and Wisconsin license plates.

There were various quotes from Lindbergh about his Excelsior. He wrote, “I liked the mechanical perfection of the motorcycle and took pride in the skill I developed riding it. I liked the feel of its power and its response to my control. Eventually, it seemed like an extension of my own body.”

There was also a display of Lindbergh’s probationary academic report from the UW, signed by a Professor Joseph D. Livermore.

We toured the home, a very nice two-story house with a big screened back porch-Lindbergh’s summer bedroom-facing the river. Under the porch was a garage containing the original Saxon touring car, now restored after being, literally, pulled apart by souvenir hunters in 1927.

Before leaving, we naturally toured the gift shop and loaded up on books and DVDs, which joined our Red Wing boots and pottery in the ever-more-densely-packed trunk of the sidecar. We got rooms at a local motel, ate dinner at an excellent roadhouse called Cabin Fever, took in Talladega Nights at the local theater (alas, The Spirit of St. Louis, with James Stewart, which I saw about six times as a kid, was no longer playing) and then rolled south in the morning.

We debated what route Lindbergh might have taken to Madison-I know of no written record-and decided he probably would have taken the river road right from his front door down through St. Cloud, the Twin Cities and Red Wing, then cut over into Wisconsin. And that’s what we did, stopping, of course, at my dad’s birthplace on Breda Street in St. Paul.

Leaving St. Paul on a short stretch of Interstate I tried for top speed and hit an indicated 67, flat out. The Ural could cruise okay in the right lane of the freeway but felt overstressed and unhappy in that environment, like a small dog in a large airport. Its RGS (Range of Greatest Serenity) was between 50 and 55 mph, at which it hummed happily, generated minimal wind blast for the pilot and felt as if it could go on forever.

Highway 61, on the Minnesota side of the Mississippi, was a little too hectic and crowded for our laid-back Ural state of mind, so it felt good when we crossed into Wisconsin for another night in Trempealeau.

I know this sounds like the worst kind of state chauvinism, but when we stopped at a scenic overlook near Fountain City, I said to Barb, “No matter which way you come into Wisconsin, from any other bordering state, things are always just a little nicer here. Greener hills, quieter roads, more curves, prettier farms. Lindbergh knew where to ride.”

There, I’ve offended all our neighbors, but I’ll stand by it.

At one point, we turned off on a heavily graveled country road to see how the two-wheel-drive system worked. I flicked the lever and the Ural motored easily through the deepest gravel, straight as an arrow. It turned normally in the loose stuff, but not at all when we got back on dry pavement. It’s a system you don’t need very often, but it makes you fearless in the face of road construction, mud, deep puddles and dirt roads.

From LaCrosse we took Highway 33, a beautiful ridge road and old pioneer route, southeast through the green hills. Barb made me stop at an Amish farm and craft shop where she bought three quilts and managed to stuff them over her legs and lap in the front of the sidecar. “An Amish airbag,”

There was a joke here somewhere, and I felt it was on us.

We dropped down to Highway 14 and rolled into Madison late in the afternoon with the UW campus and State Capitol in view. Ceremonially, we pulled up at 35 N. Mills St., the house, now remodeled to be exceedingly plain and ugly, where Lindbergh had a student apartment (with his mother, no less) on the third floor. While I took photos, a student was moving out after summer school, loading his car. I asked if he knew Lindbergh had lived in his building, and he said no.

The place had a For Sale sign on it, and I wondered if this was our chance to become student slumlords and historical preservationists, all at once. We decided to pass; there are limits to our Lindbergh fixation. Barb and I headed 22 miles south to our home and got there just before sundown.

When we got home, the Ural had covered 1015 miles in our meanderings, consumed only a trace of oil on its dipstick and averaged 27.7 mpg. There was still a little oil misting out of the rear hub, but no other problems had occurred. Steve Kring later told us the rear hubs will do that if they are even slightly overfilled during servicing. The transmission had loosened up a little bit but still wasn’t a paragon of precision. (Ural says there are newly designed gears coming next year.) Otherwise, the bike ran beautifully for the whole trip and started instantly with a prod of the button, almost before you could hear the starter motor engage.

I started it once with the side-mounted kickstarter, though it took about six quick swings of the lever to get it running.

We ran out of gas once, going on reserve at 107 miles and running flat-out at 125 miles, half a block short of a gas station in Red Wing. A pedestrian named Rob, who said he owned both a Guzzi Ambassador and an Eldorado, helped us push it to the Marathon (of all things) station. It took exactly five gallons, the claimed tank capacity. Fuel mileage was better on backroads than running fast and straight on major highways.

The fun factor was better, too, even if the trip took a little longer. Which was okay with us, as a sidecar rig isn’t about making time so much as the suspension of time. It’s a comfortable and charming observation platform that forces you to slow down slightly and look at where you are. This little five-day journey might be the most pure, relaxing fun I’ve ever had on a motorcycle trip. Not the greatest speed, distance or cornering thrills, just the best time. In a world of biz-jets, it’s a Stearman biplane.

Or maybe a Curtiss Jenny, tastefully updated and with modern electrics. E

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontBike of the Year, 2006

FEBRUARY 2007 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFlying On the Ground

FEBRUARY 2007 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMixing It

FEBRUARY 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

FEBRUARY 2007 -

Roundup

RoundupItaly Rocks!

FEBRUARY 2007 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupTen-Nine-Eight...Wow!

FEBRUARY 2007 By Bruno De Prato