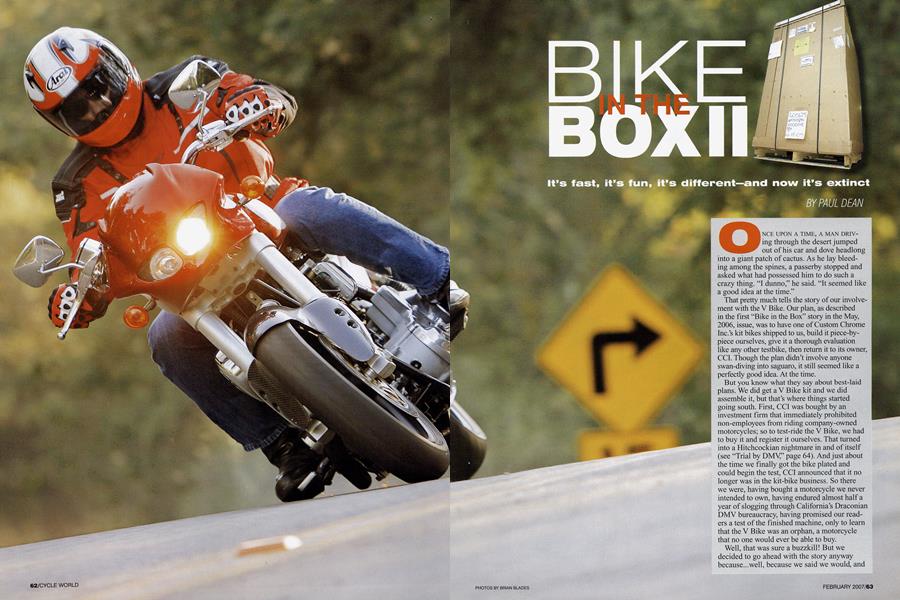

BIKE IN THE BOX II

It's fast, it's fun, it's different—and new it's extinct

PAUL DEAN

ONCE UPON A TIME, A MAN DRIVing through the desert jumped out of his car and dove headlong into a giant patch of cactus. As he lay bleeding among the spines, a passerby stopped and asked what had possessed him to do such a crazy thing. “I dunno,” he said. “It seemed like a good idea at the time.”

That pretty much tells the story of our involvement with the V Bike. Our plan, as described in the first “Bike in the Box” story in the May, 2006, issue, was to have one of Custom Chrome Inc.’s kit bikes shipped to us, build it piece-bypiece ourselves, give it a thorough evaluation like any other testbike, then return it to its owner, CCI. Though the plan didn’t involve anyone swan-diving into saguaro, it still seemed like a perfectly good idea. At the time.

But you know what they say about best-laid plans. We did get a V Bike kit and we did assemble it, but that’s where things started going south. First, CCI was bought by an investment firm that immediately prohibited non-employees from riding company-owned motorcycles; so to test-ride the V Bike, we had to buy it and register it ourselves. That turned into a Hitchcockian nightmare in and of itself (see “Trial by DMY” page 64). And just about the time we finally got the bike plated and could begin the test, CCI announced that it no longer was in the kit-bike business. So there we were, having bought a motorcycle we never intended to own, having endured almost half a year of slogging through California’s Draconian DMY bureaucracy, having promised our readers a test of the finished machine, only to learn that the V Bike was an orphan, a motorcycle that no one would ever be able to buy.

Well, that was sure a buzzkill! But we decided to go ahead with the story anyway because...well, because we said we would, and because extinct or not, the V Bike turned out to be an interesting, entertaining motorcycle. By comparison, that’s a whopping second-and-a-half quicker and 18 mph faster in the quarter-mile than the cubic kings of V-Twindom, the Kawasaki Vulcan 2000 LT and Yamaha Stratoliner, and 20 mph faster in top speed. Granted, those two Japanese cruisers were encumbered with windshields and soft bags when we tested them (September, 2006), but still.... And in roll-on performance, the V Bike would utterly annihilate either of those V-Twins. Ironically enough, though, the V Bike seems also to have inherited the unshakable stability that is typical of most Harleys, even though its chassis shares no parts or specifications with any of The Motor Company’s products. Despite its willingness to change direction, the V maintains a steady-as-she-goes demeanor in a straight line and is practically impervious to rain grooves, pavement transitions and other roadsurface irregularities that render some bikes twitchy. This means you can relax and enjoy the scenery when bopping along the open road without fear of unwittingly bouncing off a guardrail or ending up in someone else’s lane.

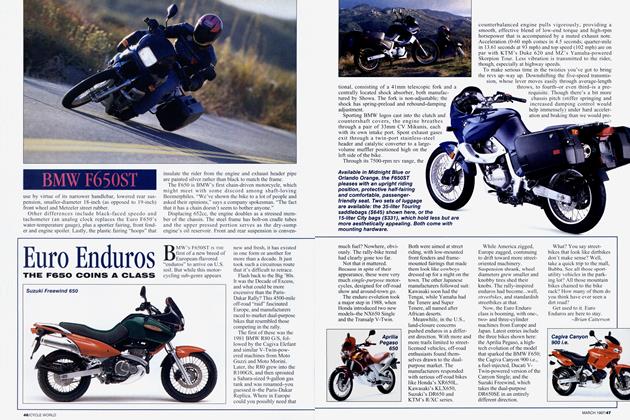

For those of you who are new to this soap opera, the V Bike is sort of a sport-standard powered by a 110-cubic-inch, 45degree V-Twin engine hooked to a six-speed gearbox, both of them CCFs own RevTech brand. The entire drivetrain-engine, tranny, swingarm and chain-driven rear wheel-is hung in a double-cradle frame via the same rubbermount system used on Flarley-Davidson’s FXR and FL models. The front end-fully adjustable Paioli inverted fork, Marchesini wheel, massive triple-clamps, Brembo brakes, 17-inch Avon Azaro sport tire-would be perfectly at home on a Ducati. The rear uses the same brand of wheel, tire and brake, mated with a pair of Progressive Suspension adjustablerebound-and-preload shocks working on a box-section steel swingarm. Bodywork consists of a solo seat/tailpiece, a 4.6-gallon steel gas tank and a fiberglass “Batman” handlebar-fairing with separate highand low-beam high-intensity headlights. Carbon-fiber fenders at both ends add a lightweight accent to our burgundy-and-silver paint scheme.

In this era of enormous V-Twins, a 110-inch (1800cc) Vee isn’t tear-up-the-front-page news. But when dropped into a vehicle that, at 559 pounds dry, weighs 200 to 300 pounds less than other bikes powered by giant V-Twins, the RevTech scoots this package down the road quite smartly. Pushed by just shy of 115 horsepower and 120 foot-pounds of torque, the V Bike laid down an 11.38-second, 119.47-mph run at the dragstrip and a top speed of 137 mph on our radar gun.

It also would out-vibrate them. The rubber engine mounts work well on a stock or near-stock FXR or FL Harley, but the V Bike is neither. The reciprocating masses in the 110inch motor (4-inch bore, 43/8-inch stroke) are considerable; and because the frame does not have even remotely as much mass as a stocker, its natural frequency and vibration-absorbing capabilities are very different. The consequence is mirror-blurring vibration in the middle and upper rpm ranges.

It’s not debilitating, but at road speeds it’s always there.

What’s more, the bike is freakin’ LOUD! Like in set-offevery-car-alarm-on-the-block loud. The D&D muffler is essentially a straight-through extension of the header, with a fat, unrestrictive 2U2-inch inlet and outlet. So obnoxious was the exhaust note that we retained the D&D “silencer” only for dynamometer, dragstrip and top-speed testing, then kluged on the only muffler we could find with the requisite inlet diameter-a tunable Hooker unit set on its quietest, “torque” setting. That may have cost the V Bike a few peak ponies, but at least it allowed us to ride the bike on public roads without showing up on a future episode of “Cops.”

No such complaints about the handling, though. The frame is rock-solid, the center of gravity is low and the steering geometry is relatively quick (25.0-degree head angle,

3.9 inches of trail). Plus, the fork doesn’t flex in the least, the shocks are decent, the tires stick like Krazy Glue and the dirt-track-style handlebar offers excellent leverage. So despite its rubber driveline mounts and chopperesque 64.5inch wheelbase, the V carves up corners easily, willingly and without wiggles or wallows.

Unfortunately, CCI chose to equip this bike with stock H-D FXR foot controls, big, protruding items never meant to allow generous cornering clearance. So just when you’re about to get the V leaned over into the fun zone, the footpegs start carving their initials in the tarmac. This is particularly annoying on the left side, where the clutch bulge in the primary cover directly behind the footpeg prevents the rider from putting the ball or toe of his foot on the peg or even tucking his boot in tightly against the case. Consequently, that boot often hits the ground during hard cornering and is swept completely off the footpeg. Too bad, because those clearance problems limit the cornering ability of what otherwise is a surprisingly capable backroad bomber.

So, too, are the hand controls H-D knockoffs,which are out of place on a bike with this one’s mission. While the Brembo front calipers and rotors deliver strong, predictable braking, they would work even better if they weren’t powered by a lever and master cylinder designed for a completely different system on a Milwaukee cruiser. Ditto for the rear Brembo, which is operated by a master cylinder and pedal lifted from an FXR Harley.

CUSTOM CHROME V BIKE

$15,000

It’s also a reasonably comfortable bike, considering that the suspension is on the taut side and the Corbin saddle is exceptionally hard. But the fork and shocks soak up smallto medium-sized bumps unexpectedly well, probably due in part to the bike’s comparatively low unsprung weight; and despite the seat’s stiffness, its superb shape helps it distribute the force of those impacts across the rider’s entire butt.

So the ride on most surfaces is pleasant if not plush. But on rougher roads, the jolts delivered to the rider can be abrupt and jarring whether the suspension is set on full soft or full stiff. The V tracks nicely over large road imperfections, even when cornering, but the ride unquestionably is harsh.

Nothing especially bothersome about the rest of the ergonomics, aside from the previously mentioned left boot/primary cover interference. The rider sits bolt upright, knees not quite at a 90-degree angle, arms extended forward naturally to the grips. The reach to the bar is a bit on the long side, but not a problem for most riders 5-foot-11 or taller.

In reality, though, the reach to the handlebar isn’t going to be a problem for anyone, regardless of size, since CCI is no longer selling this or any other kit bikes. Our V Bike turned out to be a more capable, less problematic motorcycle than we originally imagined it might be, one that with a few wellthought-out modifications (tidier hand and foot controls at the top of the list, along with a more civil exhaust) could rival quite a few production machines for sheer fun factor. But in light of CCI’s recent decision, that’s a moot point.

So far, CCI has offered no reason for its sudden change in strategy, but we have to assume that the specter of liability played a major role. Once a kit bike was in the hands of its assembler, CCI had no control over the quality of the build; yet if the bike were ever involved in an accident, the company could be held responsible, even if the crash were the result of faulty workmanship. If that is truly the case, you really have to wonder what CCI _ was thinking when it decided to market kit t bikes in the first place. It must’ve seemed like a good idea at the time. □

To read “Bike in the Box, Part I,” visit www.cycleworld.com

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

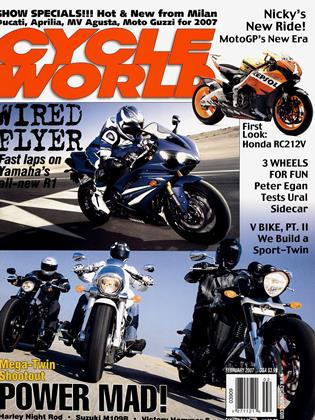

Up Front

Up FrontBike of the Year, 2006

FEBRUARY 2007 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFlying On the Ground

FEBRUARY 2007 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCMixing It

FEBRUARY 2007 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

FEBRUARY 2007 -

Roundup

RoundupItaly Rocks!

FEBRUARY 2007 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupTen-Nine-Eight...Wow!

FEBRUARY 2007 By Bruno De Prato