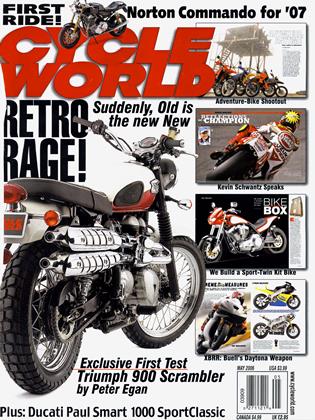

CW PROJECT

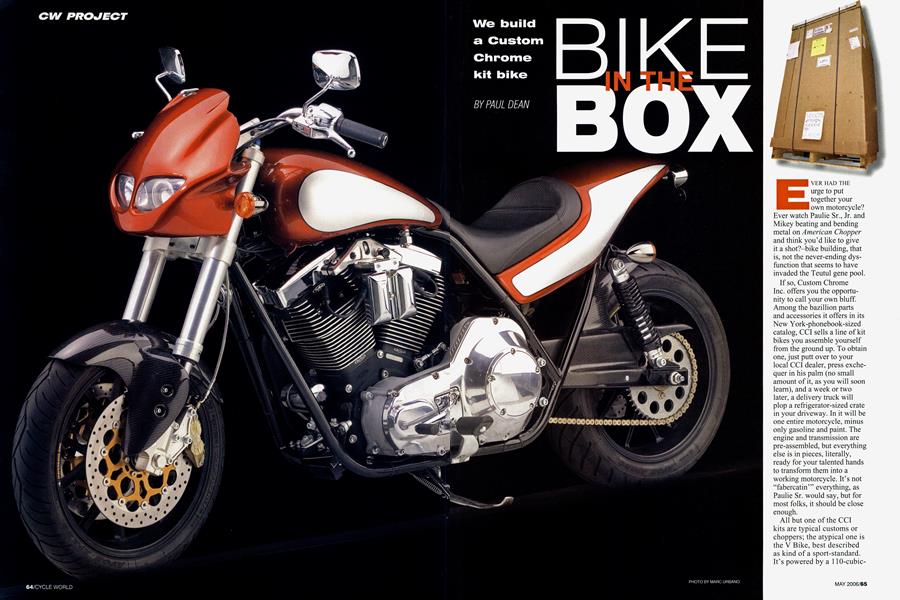

BIKE IN THE BOX

We build a Custom Chrome kit bike

PAUL DEAN

EVER HAD THE urge to put together your own motorcycle? Ever watch Paulie Sr., Jr. and Mikey beating and bending metal on American Chopper and think you’d like to give it a shot?-bike building, that is, not the never-ending dysfunction that seems to have invaded the Teutul gene pool.

If so, Custom Chrome Inc. offers you the opportunity to call your own bluff. Among the bazillion parts and accessories it offers in its New York-phonebook-sized catalog, CCI sells a line of kit bikes you assemble yourself from the ground up. To obtain one, just putt over to your local CCI dealer, press exchequer in his palm (no small amount of it, as you will soon learn), and a week or two later, a delivery truck will plop a refrigerator-sized crate in your driveway. In it will be one entire motorcycle, minus only gasoline and paint. The engine and transmission are pre-assembled, but everything else is in pieces, literally, ready for your talented hands to transform them into a working motorcycle. It’s not “fabercatin”’ everything, as Paulie Sr. would say, but for most folks, it should be close enough.

All but one of the CCI kits are typical customs or choppers; the atypical one is the V Bike, best described as kind of a sport-standard. It’s powered by a 110-cubicinch RevTech Evo-style V-Twin engine mated to a six-speed transmission and cradled in a double-downtube, twin shock steel frame.

r That's common H-D-clone fare, but the V Bike is also fitted with equipment you don't normally find on that class of motor cycle-and that also contributes mightily to the kit's $15,000 price tag: a ftilly adjustable Paioli inverted fork; ultra-light, 17-inch Marchesini cast wheels; triple-disc Brembo brakes; Avon Azaro sport tires; and a quarter-fairing with a pair of high-intensity head lights staring out the front. The wheelbase is an ultra-long 64.5 inches, but the steering geom etry (25-degree head angle, 3.9 inches of trail) is more sport than chop. The chassis sits high enough to allow decent corner ing clearance, and the riding position is dirt-track reminis cent. So, while the drivetrain is very H-D custom-esque, the rest of the bike clearly is not.

Intrigued by this machine from the moment we first laid eyes on one, we decided not just to test a V Bike but also to build one. I agreed to do the build myself in the Cycle World shop, then we'd subject it to a thorough road test, just like any other motorcycle.

When the crate arrived and I surveyed its contents, I realized that putting this bike together would take much more time than I'd imagined. In addi tion to the major components, there was box after box after plastic bag filled with nuts, bolts, washers, clips, springs, connec tors, spacers, big brackets, little brackets, zip ties, loops of tubing, miles of wiring and an assort ment of stuff! couldn't identify. When I laid everything out on the shop floor, it looked like a Home Depot had exploded. This was going to take "some assembly required" to new heights.

After unpacking everything, I discovered that the V Bike arrives without something else besides gas and paint: instructions. The engine, transmission and starter come with basic instal lation sheets, and a few rudimentary wiring , diagrams offer some clue about which wires p1ug into what. But as far as actual assembly is i:~oncerned (how to mount the seat, gas tank and `fairing; routing the wiring; installing the instru ments and light ing; which spac ers and brackets go where, etc.),

you’re on your own. No instructions. No pictures. No drawings. The Teutuls and their colleagues may build most everything from scratch, but they also design most everything. The V Bike was designed by someone else, and you have to divine how it all goes together.

I started by pre-assembling“mocking up,” it’s called-the frame, swingarm, gas tank, fairing, tailpiece and numerous brackets, all of which arrive au naturel. Pre-assembly was necessary to make sure they fit properly so I wouldn’t have to grind, file, drill or cut anything after it was painted. This pro cess involved me frequently holding an unfamiliar bracket in one hand and scratching my head with the other as I tried to figure out what it was, where it was supposed to go and which nuts, bolts or screws would keep it there. I spent quite a few hours performing this satanic ritual, and even more time rooting around in dozens of packages searching for the required hardware.

After mockup, it was off to one of the area's top powder coaters, Specialized Powder Coatings in Huntington Beach (714/901-2628; www.special izedcoating corn) with the frame, swingarm and brackets. I wasn't looking for anything elaborate, so Specialized just applied a nice, tough gloss black. The tank, fairing and tailpiece went to Boris Landoff at California Cycle and Watercraft in Costa Mesa (714/979-3911), who laid on a simple but eye-catching paint scheme using House of Kolor Candy Burgundy accented by Metallic Silver.

While those parts were out being prettied up, I did a final assembly of the rest of the bike. The fork, shocks, wheels and brakes all bolted up with out a hitch; so did the engine, trans mission and swingarm, which float in the same rubber-mount system used on < H-D's FXR and FL models

Not everything went so smoothly After assembly, the primary drive leaked because the kit provided the wrong 0ring; I had to remove the entire primary and install a thicker 0-ring. The starter motor's flat-black paint had been applied over chrome, and the plating increased the diameter of the starter's nose enough to prevent it from slipping into its close-tolerance opening; I had to file away all of the chrome on the affected area to get the starter to fit. As delivered, the six-speed gearbox wouldn't shift properly until I replaced a deformed snap ring on the shift shaft. The supplied gas-tank mounts allowed the tank to wal low around, calling for an "alterization," in Teutul-speak, of the front mount. The threaded portion of the rear axle was too short and had to be machined and rethreaded. The wiring diagrams were so vague that it took me a couple of hours with a multimeter to identify many of the electrical connections-during which, I found that a supplied gang plug had been wired incorrectly at the factory. The carbon-fiber rear fender/chainguard was improperly molded and refused to align with the tire and chain; only after CCI sent me two more fenders did I get one that even came close to fitting correctly.

Wait, there's more. When the build was finished and I began the break-in process, I discovered that the bottom edge of the steering head was drag ging on the top side of the lower triple-clamp, acting like a non-adjust able steering damper. I had to remove the front end and install a shim under the inner race of the lower steering head bearing.

All tolled, I racked up 110 hours building the V Bike. Most of it was in actual assembly, but a significant percentage was spent performing tasks that would have been unneces sary if the kit had included instruc tions and all the pieces had been properly made. A few weeks after I reported this to CCI, my contacts there told me that the company was producing both written and video instructions, and that the problems I'd experienced with incorrect or improperly made parts would be rectified in future V Bike kits. If that turns out to be the case, building one will be much easier.

Even so, this will never be a job for inex perienced mechanics or people who keep their tools in a kitchen drawer. You need a full assort ment of American and metric sockets and wrenches (the bike uses both species), and you'll either have to buy or borrow several special tools (a press for installing the swingarm pivot's Cleveblock bushings; a clutch-spring compressor; large sockets and hub-holding tools for tightening the clutch and compensator-sprocket nuts). I borrowed those tools-and got a few useful engine and gearbox assembly tips and shortcuts-from Bruce Fischer, local H-D guru and occasional CWcontributor.

You could, of course, have a mechanic/builder put the bike together for you. But it won't be a cheap build. Some of the qualified people I know who do such work charge a minimum of $5000, and the price escalates from there if the job exceeds a certain number of hours.

That seems fair, given that it took me 110 hours; at a typi cal shop rate of $65 to $70 an hour, we’re talking more than $7000 in labor alone. Throw in $ 15 grand for the kit and around $ 1600 for tax and license, plus another thou for painting and powdercoating, and you end up with a $25,000 motorcycle.

Obviously, building a V Bike is not the cheapest route to a custom motorcycle. But it’s far less expensive than having the Teutuls or most other custom builders brew one up from scratch. And there’s a powerful sense of pride and satisfaction derived from having put together an entire motorcycle on your own.

So, how's the V Bike work? During break-in, its performance seemed very prom ising, but I can't say anything more conclusive until we've completed the full test.

Normally, I despise the clichéd phrase so many writers use at the end of a story that will have a follow-up: Stay tuned. But in this case, it's appropriate. So stay tuned. At

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

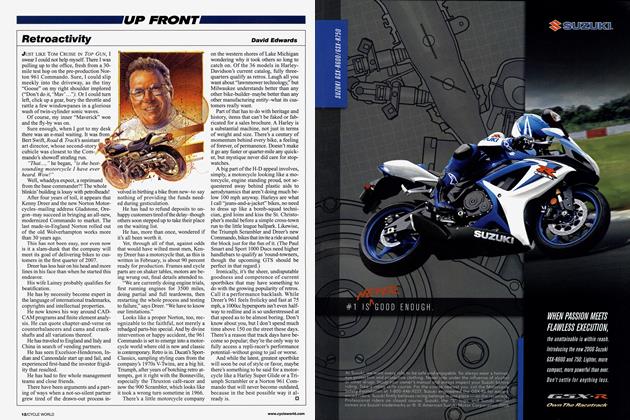

Up FrontRetroactivity

May 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsIt's Hard To Beat A Motorcycle

May 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBeguiling Style

May 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2006 -

Roundup

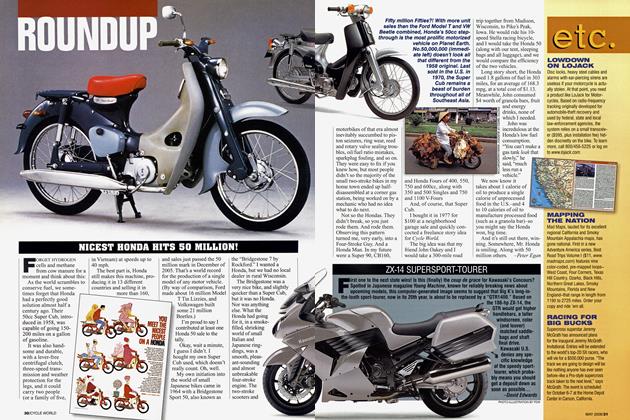

RoundupNicest Honda Hits 50 Million!

May 2006 By Peter Egan -

Roundup

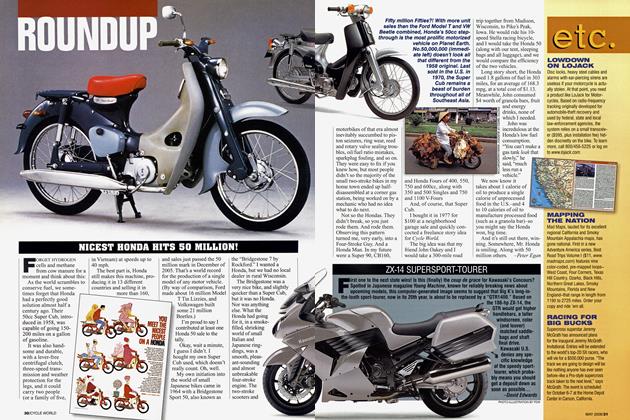

RoundupZx-14 Supersport-Tourer

May 2006 By David Edwards