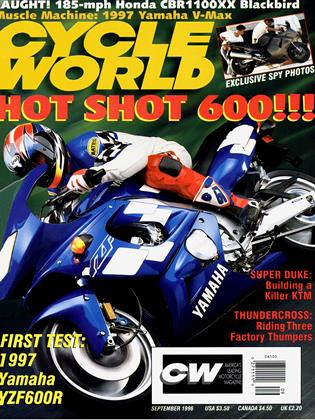

SUPER DUKE

CW PROJECT

KTM's bare-knuckled street brawler

BRIAN CATTERSON

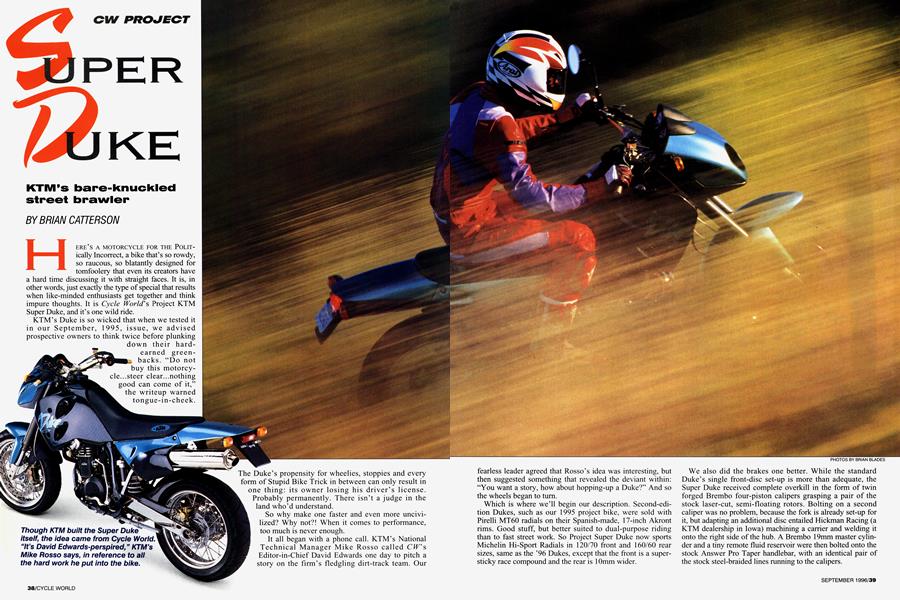

HERE'S A MOTORCYCLE FOR THE POLITically Incorrect, a bike that's so rowdy, so raucous, so blatantly designed for tomfoolery that even its creators have a hard time discussing it with straight faces. It is, in other words, just exactly the type of special that results when like-minded enthusiasts get together and think impure thoughts. It is Cycle World's Project KTM Super Duke, and it's one wild ride.

KTM’s Duke is so wicked that when we tested it in our September, 1995, issue, we advised prospective owners to think twice before plunking down their hardearned greenbacks. “Do not buy this motorcycle...steer clear...nothing good can come of it,” the writeup warned tongue-in-cheek. The Duke’s propensity for wheelies, stoppies and every form of Stupid Bike Trick in between can only result in one thing: its owner losing his driver’s license. Probably permanently. There isn’t a judge in the land who’d understand.

So why make one faster and even more uncivilized? Why not?! When it comes to performance, too much is never enough.

It all began with a phone call. KTM’s National Technical Manager Mike Rosso called CW's Editor-in-Chief David Edwards one day to pitch a story on the firm’s fledgling dirt-track team. Our fearless leader agreed that Rosso’s idea was interesting, but then suggested something that revealed the deviant within: “You want a story, how about hopping-up a Duke?” And so the wheels began to turn.

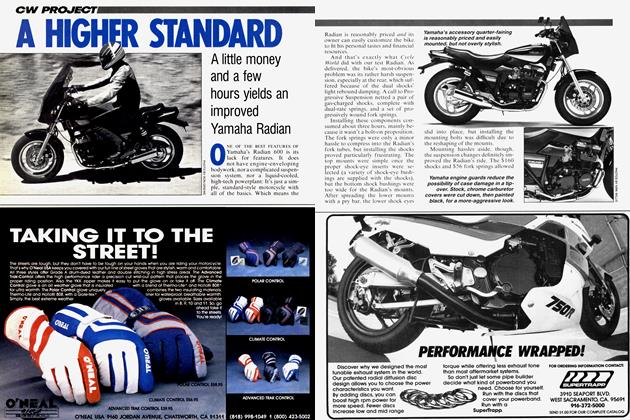

Which is where we’ll begin our description. Second-edition Dukes, such as our 1995 project bike, were sold with Pirelli MT60 radiais on their Spanish-made, 17-inch Akront rims. Good stuff, but better suited to dual-purpose riding than to fast street work. So Project Super Duke now sports Michelin Hi-Sport Radiais in 120/70 front and 160/60 rear sizes, same as the ’96 Dukes, except that the front is a supersticky race compound and the rear is 10mm wider.

We also did the brakes one better. While the standard Duke’s single front-disc set-up is more than adequate, the Super Duke received complete overkill in the form of twin forged Brembo four-piston calipers grasping a pair of the stock laser-cut, semi-floating rotors. Bolting on a second caliper was no problem, because the fork is already set-up for it, but adapting an additional disc entailed Hickman Racing (a KTM dealership in Iowa) machining a carrier and welding it onto the right side of the hub. A Brembo 19mm master cylinder and a tiny remote fluid reservoir were then bolted onto the stock Answer Pro Taper handlebar, with an identical pair of the stock steel-braided lines running to the calipers.

Because bikes with long-travel suspension tend to get a bit wonky when the rear end is hacked out in comers, the Dutch-made WP fork and shock both had their travel shortened by 1.8 inches. The shock is set-up to easily accommodate different rider weights or road conditions, thanks to the addition of a hydraulic spring-preload adjuster.

In an effort to save weight-and because the Super Duke is not intend-

ed to carry passengers-a lightweight, 40mm-shorter aluminum subframe replaces the standard chrome-moly unit, and the passenger grabrails and footpegs were eliminated; otherwise, the frame is the same dirtbike-derived unit as before.

To spruce up the rolling chassis’ appearance, the fork’s stanchion tubes were anthracite-coated, the shock’s piggyback reservoir was carbon-clad and the swingarm was chrome-plated. Fast Company supplied the custom carbonfiber subfender/chainguard (soon to be offered by KTM’s K Style accessories line), plus a carbon-fiber panel onto which Rosso mounted all the bike’s electrical components.

Ah yes, carbon. While the bodywork looks to have been made from the stuff, it is in fact good old-fashioned plastic covered with faux-fiber decals. What is neat about the bodywork is the paintwork: Rosso found an attractive teal green metallic that he sent all the way to the factory in Mattighofen, Austria, to be applied. Complementing the paint are colorcoordinated custom decals by Next World Design and tastefully embroidered seat-cover logos by Chuck’s Custom Design, just down the street from KTM Sportmotorcycle USA’s Lorain, Ohio, headquarters. A smaller-than-stock taillight and license-plate mount from an EX/C enduro bike caps off the Super Duke’s super look.

As trick as our project bike’s chassis is, however, its engine is even tricker. Drawing on the experience of employees Wolfgang Felber and Josef Frauenschuh in supermono roadraces and supermotard events, the KTM factory supplied a 660 rally motor similar to the one our own Jimmy Lewis campaigned in the Granada-to-Dakar Rally (see CW, May, 1996). Presto, instant horsepower!

Surprisingly, the rally motor isn’t that different from the standard 620 (actually 609cc) Duke’s. The liquid-cooled, counterbalanced, four-valve, sohc Single features a lmmlarger (102mm) bore and 4mm-longer (80mm) stroke, giving it 653cc of displacement, plus a taller first gear in its gearbox. The most significant difference is its lubrication system: Unlike production KTM four-strokes, which use the frame’s downtube as an oil tank, the rally motor’s oil is contained entirely within.

With the factory delivering a complete engine, the only thing left for Rosso to do was clean up the intake manifold to match the oval-bore (37 x 41mm), flat-slide Qwik Silver II carburetor. Like the stock 38mm unit, this carb is “jetless”-that is, fuel flow is regulated only by a tapered needle with a threaded height adjustment; there are no main or pilot jets. There are, however, two very convenient features: a handlebar-mounted cold-start enrichening lever and a remote idle adjuster that hangs on the end of a cable at the left side of the carb.

Replacing the stock airbox on the intake side of the engine is a pleated K&N air filter. Replacing the stock, Austrian-made Remus exhaust is a stainless-steel, 2-into-l, internal-disc system made by Hans Luenger of SuperTrapp. Unfortunately, the pipe cracked at the middle mount during our test; judging by the black smudges the tire left along the muffler’s inner edge, we suspect a clearance problem.

Like every KTM produced prior to the 1996 electric-start Duke (see the riding impression, page 42), the Super Duke is kickstart-only. Fortunately, it’s also fitted with KTM’s excellent automatic centrifugal décompresser, which eases kickstarting dramatically-provided the engine is warm, that

is. The high-compression 660 rally motor is a bitch to start when cold; you have to know just how much throttle to give

it, and just when, or you’ll quickly find yourself considering alternate means of getting to work. Once it’s warmed-up, however, it’s a reliable first-kick, no-throttle starter.

Depending on how you feel about your neighbors, you may want to think twice before starting the Super Duke early in the morning. Because in a word, it is loud. It’s not that bad at idle or under acceleration, but close the throttle abruptly and it backfires something awful-more than one motorist rolled his car window up as the Super Duke pulled to a stop beside him. Appropriately, the tachometer is marked in “beats per minute,” which in the case of the pumped-up rally motor sound as if they’re being produced by a dreadlocked percussionist pounding a steel drum. The audio entertainment continues at low revs, too, where the exhaust note resembles the world’s loudest broken watch: “tock, tock, tock...”

Carburetion is fine at wide-open throttle (where, face it, you spend a great deal of time on a single-cylinder streetbike), but things aren’t so rosy at partial throttle; between 4500 and 5500 rpm, there’s a major surging condition.

It’s fairly easy to forgive the Super Duke its quirks, however, because its performance makes up the difference. Compared to a standard Duke, the Super Duke makes more power, sooner. The 660 rally motor pumps out a peak 45.3 horsepower at 6500 rpm (versus the 620’s 41.9 bhp at 6750) and 40.7 foot-pounds of torque at 4750 rpm (versus 35.1 at 5350). Furthermore, the Super Duke is nearly three-tenths of a second quicker in the quarter-mile (12.66 versus 12.97), and it takes a full second less to accelerate from 40-60 mph and 60-80 mph in top gear. That, performance fans, is a huge improvement.

Given its healthy motor and light weight (302 pounds dry, compared to 323 in standard trim and 341 for the ’96 electricstart model), the Super Duke makes quick work of twisty backroads. Its long-travel (by streetbike standards) suspension fends off anything in its path, yet keeps fore-and-aft pitching to a minimum. The chassis is sure-footed and very stable; only ham-fisted muscling of the wide handlebar produces any sort of twitching sensations. The brakes, as you’d expect, are awesome, though like some comparably equipped Ducatis we’ve sampled, lever feel is a bit mushy. No, the Super Duke won’t beat a sportbike on Racer Road, but it’ll flat annihilate one down a tight, bump-riddled canyon. Buell SI Lightning owners better find new hunting grounds...

So, what would it cost to build a Super Duke Replica? It’s difficult to tell. Some parts, such as the factory rally motor, simply aren’t for sale, while others are one-off prototypes that the makers would only produce if there were sufficient demand. Pressed for a replacement cost for our testbike insurance policy, Rosso estimated $25,000.

Is the Super Duke worth that much? No way. Not when you can buy a Bimota for thousands less. But the good news is that the Super Duke wouldn’t cost nearly that much if it were mass-produced-and for KTM, it is a very likely next step.

Would the Super Duke sell if it were priced at $10,000?

Considering that the factory had no trouble selling every one of the 1200 standard Dukes it built in 1995 for just under $8000, you’d have to assume so. Just do us a favor: If you want to see it happen, don’t call us, call KTM. And please try to remain a responsible citizen. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMillion Mile Man

September 1996 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsMinibike Flashback

September 1996 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCRising Duty

September 1996 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

September 1996 -

Roundup

Roundup1997 Honda Cbr1100xx Super Blackbird Sighted

September 1996 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupSupercross Superbike

September 1996 By Jimmy Lewis