High Banks, BIG Questions

RACE WATCH

Unraveling Daytona’s Gordian Knot

KEVIN CAMERON

SIXTY-SEVEN FORMULA XTREME MACHINES lined up for the 65th running of the Daytona 200 this past March. Up front were six or more factory or semi-factory Hondas and Yamahas. Such modified machines begin with European Supersport kit parts. Also in the field were four of the new and intensely controversial Buell XBRRs-the fastest of which was qualified 8th by former MotoGP rider Jeremy McWilliams. The other 57 machines were Supersport bikes on the mandatory slicks. There were no factory Ducatis, Kawasakis or Suzukis.

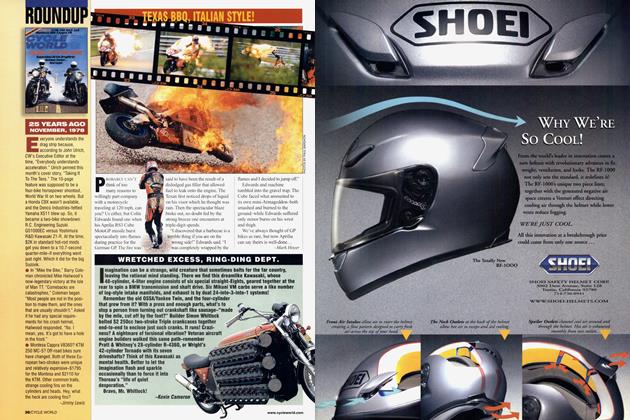

The race ran its course. Making his Yamaha debut, Eric Bostrom led for 10 laps but was rubbed off in traffic by the Hondas of Jake Zemke and Miguel Duhamel and, apparently, lost the steam to recover. Duhamel led from lap 18, then crashed in Turn One 26 laps later while leading by 12 seconds. Remounting heroically, he set about scrubbing the egg from his face.

On lap 56, a NASCAR-esque “Debris on the track!” call brought out the pace car-Daytona being the only place where such a policy is followed on the AMA circuit-and what ensued left everyone wondering if anyone was in charge. Roadrace Manager Ron Barrick drove the car onto the course but in front of the wrong rider, fourth-place Bostrom, confusing everyone in the facility, including raceleader Zemke, stuck mid-pack with Erion Racing’s Josh Hayes. For reasons that even he couldn’t explain, Barrick remained in front of Bostrom until the restart; and because he had not been accompanied by the promised pace-car passenger who was supposed to help get the field in the proper order, he never corrected the lineup. So the restart went off with fourth-place Bostrom and fifth-place Duhamel still ahead of the pack but almost a lap down, even though they had been much closer to Zemke before the full-course yellow. During all this confusion, even the track announcer was speechless.

The finish order was Zemke, Hayes, then Yamaha-mounted Jason DiSalvo, Bostrom and, incredibly, Duhamel. All the Buells were out with driveline or other problems.

Downgraded to 15 laps because of continuing concerns over tire safety, the 26machine Superbike race was won by (may I have the envelope please?) Mat Mladin on aYoshimura Suzuki GSX-R1000. Unable to pull away from closely pursuing teammate Ben Spies, Mladin activated a fiendish plan at the very instant when Spies had the most on his mind-launching from the Chicane on the last lap. Did Mladin miss a shift? Surely not. In any case, Spies shot past into the vulnerable last-lap lead. Mladin’s drafting pass just before the finish line was timed to be unanswerable-by .032-second. Spies was both philosophic and graceful about his second place. Mladin and Spies were joined on the podium by Duhamel on the now greatly improved U.S.-built Honda CBR1000RR. Neil Hodgson (Ducati) and Tommy Hayden (Kawasaki) rounded out the top five.

Now let us tackle the avalanche of pre season controversy. Everyone knows that putting some kind of Harley-David son into a racing class is a recipe for suc cess, right? The most recent proof is the NHRA's Pro Stock Motorcycle drag-rac ing class, which includes the Vance & Hines "V-Rod" and faux Buells from S&S and Muzzys. When the curiously named AMA Formula Xtreme class was creatI, a rules niche was sensibly provided r a 1340cc air-cooled pushrod V-Twin. u1d anyone take the bait? Not at first.

It almost happened last year but, at the last moment, funding slipped away, and no Harley-powered Buell racebike with righ teous sound appeared to summon the faithful from Main Street. In this past off season, we learned such a bike had now been designed and would be tested at Daytona. The entire planned build of these 50 XBRRs was sold in as many seconds, just as was Harley’s “Destroyer”-the drag version of its youth-market experiment V-Rod.

After one planned Buell Daytona test blew away in a hurricane, I was invited to observe at the second. One day’s running revealed that either the stronger torque pulsing of the lightened crank or the hammering of comer-entry rear-wheel hop was breaking the special single-row primary drive. Buell was fortunate to have the services of 41-year-old McWilliams, the very experienced rider who is doing a lot of development riding these days. He thought the bike potentially fully competitive but needed a back-torque-limiting or “slipper” clutch to banish wheel hop from comer entry. The engines ran with 100 percent reliability.

The next test, in Texas, was also encouraging (see “Extreme Measures,” CW, May). Wind-tunnel work had revealed that the bike was only 3 mph faster with than without its fairing. Erik Buell himself spent three 24-hour days in the development shop, cutting up fairings and shaping foam to make new test articles. Improved means of pushing air through the fins of both cylinders were devised. The new fairing worked at Texas World Speedway, adding something like 12-15 mph to top speed. Now the Buells were close.

Rumors move across the world like smells through a house. People began to wonder who thought FX pushrod aircooled V-Twins should have 1340cc. They muttered about the XBRR’s differentfrom-stock crankcases. If the fuel is in the frame and the rules allow fuel tanks to be enlarged, did that mean only Buell could modify its frames? Tempers flared and telephone lines grew hot.

On January 24, the AMA’s CEO of Pro Racing, Scott Hollingsworth, was fired. To complete the excision, the separate corporation that the AMA had created specifically to handle Pro Racing, Paradama, was itself vaporized and its functions taken back within the AMA. This corporation had been created for two specific purposes: 1) to remove any legal threat to the AMA’s non-profit status from possible racing income; and 2) to create a separate and professional source of competition management, ending a long history of parochial interference and/or policy reversals by the AMA’s board of trustees. It had been hoped that this would at last allow development of consistent and reliable policy making for the sport. Now, all that is gone.

While industry moguls enjoyed 5-degree weather at the annual Indianapolis Dealer Show, Honda weighed in as well, announcing its executives would no longer serve on AMA boards. The Honda press release said, part: “Recently.. .conflicting interests within the AMA organization have caused a division of ideology and a blurring of the vision that American Honda has always supported. Recent issues, including the departure of dedicated individuals from AMA Pro Racing and its inability to stand by its own rulebook with regard to recent Formula Xtreme considerations, have been particularly alarming.”

At the end of the following month, it was announced that the amiable Merrill Vanderslice, VP, Director of Competition, had resigned. The implication was that this absolved the AMA from having approved the Buell for competition. All copies of the homologation papers were said to have disappeared.

At Daytona, I walked up and down pit row, asking team managers for their views on the Buell homologation and its possible meaning. Higher management seems to understand that a Harley presence in AMA racing is entirely desirable. At the team level, though, emphasis is rightly on the rulebook. Yamaha’s Keith McCarty showed genuine heat as he noted that the rulebook and its stability are the basis for all planning. Who is going to invest big money in racing in a class that’s vulnerable to capricious or even secret rules changes? What guarantees that a company’s investment in a racing class will not be swept away by personnel switcheroos? If only Buell can make a new crankcase and Paradama is temporary, just what can the other teams rely on?

A Daytona practice ran, I did the numers again. The Buell 1340 is just under two-and-a-quarter times the displacement of a souped-up 600 that turns twice the rpm. Does that give a breathing advantage to the Buell? It would if two valves and air-cooling were the equal of four valves and liquid-cooling. It would if the Buell’s pushrods and rocker arms control valves just as well as double-overhead cams do. But, in fact, the Buell’s traditional features reduce the intensity of each combustion event. Being air-cooled, its heads run hotthe front currently at 390 degrees, the rear at 460 F. Onion rings become golden brown at 350 degrees, and paper famous ly burns at Fahrenheit 451. The only wa; to keep that temperature from causing deto nation is to retard the ignition timing limit compression ratio-either way cutting combustion pressure.

The Buell has plenty of good qualities. McWilliams slowly crept upward from practice to practice, finally qualifying 8th. This was just fast enough to reach the bottom of the factory group, confirming the basic fairness of the homologation.

In the larger sense, the Buell’s presence was an experiment to see what would happen if the “sugar” of a novel motorcycle were added to the bland sameness of a field of inline-Four 600s. Is Daytona’s International Speedway Corporation wrong in wanting to see the FX class jazzed up by Harley partisanship? They remember when Harley BoTT bikes brought fans to fill the “Hog Heaven” seats on the back straight. If even 10 percent of the free-spending Daytona downtown crowd could be convinced to enter the speedway, it would make a huge difference.

Now, remember last Daytona, when the 200-mile race became FX instead of Superbike. The manufacturers want most to sell l000cc machines, so they weren’t pleased. Tire failures in practice spooked ISC, reminding them that trouble starts above 180 mph on their track. Their line was that, “l000cc machines have now outgrown America’s racetracks.” Therefore, a new premier class was needed, so why not FX? But FX, as it was, smelled like a lash-up-a few breathed-upon Hondas with star riders, cruising ahead of a re-run of Supersport. Where’s the novelty? Spectators and riders alike complained that the 200 was being downgraded to “a mini-bike race.” This is a hard sell. For 2006, Yamaha and Buell joined FX, but this didn’t stampede Suzuki, Kawasaki and Ducati. All of the above being true, FX advocates desperately needed Buell in the class.

Through practice, it became clear that the Buell could be made significantly faster in several ways. McWilliams had run with a German-made slipper clutch in early practice and it did ease corner entry. At the same time, it slipped all the way around the circuit, warping its plates as engine power cooked this “blue-plate special.” This experience will lead to improved hardware, but the slipper was shelved for the 200. Why didn’t it work? Possibly because the engine’s light crank produced larger-than-expected torque spikes.

Because of its very short wheelbase and its tall office building of an engine, the Buell was seldom on two wheels at the same time. It either lifted its rear during braking or its front during acceleration, limiting maximum acceleration and braking. Therefore, further options in wheelbase and center-of-gravity location might be nice-if unlikely under the rules.

Like the Harley VR1000 Superbike before it, the Buell has only a five-speed gearbox-because big Twins have torque everywhere, right? Despite this, there was serious discussion of a six-speed. Alas, no room. Another possible problem was that racing gearboxes need extra dog backlash to provide time for dog engagement to take place during shifts. Harley’s gear machine makes gears with five dogs. Again, a six-speed, three-dog box lay outside the possible.

Erik Buell rejoiced that his engineers were away from their computer screens, colliding with raw reality on Daytona’s Big Black Dyno. “This is so valuable,” he kept saying, grinning broadly. Racing does improve the breed. Good ideas are not the same as good hardware.

But what about the AMA and the confusion surrounding it? It has been suggested that the AMA hire men of reputation and intelligence to make roadracing a success. Ex-Honda team chief Gary Mathers and current Supercross manager Steve Whitelock are two popular examples. Yet you know what their response would be to such a proposal: “I’m not renting my reputation to some Board of Reversal to wipe up its mistakes with.” Here are some of the roadrace-management possibilities that face the AMA: 1) Continue the status quo-the past as future. Appoint unknown and malleable persons to racing management as rubber stamps for the Board of Trustees; 2) Promise complete independence to capable, intelligent managers, then reverse their decisions if disapproved by the board. This is what in the 1990s forced the creation of Paradama. Previous “czars of racing” have bitten the dust in this way; 3) Imposed solution-old style. International Speedway in desperation sends one of its own people to manage AMA racing as it did in the past with Lyn Kuchler. The AMA/ISC relationship is old and strong; 4) Imposed solution-new style. U.S. motorcycle importers form an IRTA-like organization that dictates a Supercross-style solution based on outside professional management and promotion. Think it over,

Erik Buell got 99th-percentile determination and energy. He’s hardheaded to a fault. His first true love is racing (he’s a former Yamaha TZ750 rider), and he was so excited near end of practice that he could no ger go out to the pit wall. It is see the actual management of a corf tion so deeply into racing (as of the more traditional golf or debentures). Buell was fortunate to have McWilliams on his bike, for McWilliams comes with his own CAD chassis setup software and vast experience from major GP teams. He can lift Buell racing toward its goals. Even though all four of the bikes were out before the end of the race, you could sense the eagerness of Buell’s engineers and staff to get back to the plant and begin to implement all they had learned. Plans! Great stuff about to happen! Pray for funding.

Why were the XBRRs out? Engines had run strongly and reliably. Two bikesthose of Mike Ciccotto and Germany’s Rico Penzkofer-broke the clutch-hub extension that carries the snap-ring retaining the clutch-diaphragm spring. Was this porosity in a bad batch of die-castings? Was it the hammering from rear-wheel hop? On McWilliams’ bike, the toothed wheel controlling engine timing had broken free. Steve Crevier’s Pascal Picottesponsored machine had an undetermined internal problem. Ah, well, even resourceheavy Yamaha, which showed the speed to win, failed to do so. Daytona is uniquely difficult-an accelerated engineering graduate school.

Orbiting around the Buell pit in his golf cart was ex-racer Steve McLaughlin, wearing his signature straw hat. He has brokered the Buell into FX, just as in the 1980s he brokered Superbike as a replacement for mostly two-stroke-based Formula 750. A whisperer came to me and murmured, “McLaughlin is really just a shill for ISC, trying to put over their FX deal now just as he put over Superbike for them 20 years ago.” This is news? McLaughlin is a fast-talking, witty veteran of years of race promotion in Europe-no one’s shill. So what was he doing in Daytona? What is the next move likely to be, and from whom will it come?

Clearly, McLaughlin (below) is a key figure. He talks to everyone. He carries in his head the expressed wishes of the important players, and he explains the position of each one to the others, adding his own insights and suggestions, seeking useful compromise.

This makes me think of Averell Harriman, the special envoy of World War II who shuttled constantly by air from President Roosevelt to Churchill to Stalin.

Each leader had his own separate agenda, conflicting with everyone else’s, but none could move forward until the big problem of Hitler’s Wermacht was dealt with.

The AMA-regional in its outlook-can’t be expected to make a major sport out of roadracing as it is in Europe. Its primary job is serving the membership, as AAA serves its membership. ISC’s business is filling seats, not managing a kind of racing it little understands. The motorcycle importers want to sell bikes. Yet an expanded, better-promoted sport would serve the interests of all. How can agreement on a plan of action be reached?

FX has other problems beside the manufacturers’ desire to race and sell 1000s. If the major modified class is lOOOcc Superbike, national series such as AMA and British Superbike can use equipment developed for it. Adding a modified 600cc class requires makers to fund a new, separate program. How many R&D programs can they afford? Can’t we just bolt on European Supersport kit parts? Yes, but for a privateer, they are prohibitively expensive, so FX runs as two races in onefactory/kit bikes up front, with private Supersport machines fattening the grid.

Right now, the AMA has four roadrace classes: Superbike, Superstock, FX and Supersport. At first, I thought this was an AMA insurance plan. If Superbike can’t keep its tires together, we fall back on Superstock, or if FX fails to pull entries, etc. But these classes have had an unexpected result: Each of the Big Four has adopted a class it can win. Suzuki has Superbike, Honda has FX, and Yamaha and Kawasaki trade off in Superstock and Supersport. This way, everyone can justly claim, “Brand X Takes Daytona,” and run their “win ads” in Cycle News. Uh, okay, but by diluting competition, doesn’t this whack the status of each class and kill the suspense? Could that be why so many people are saying that Daytona just doesn’t feel as important as it used to?

But back to the particular: Will the Buells be back, rearmed and ready to penetrate deeper into the lead pack? I certainly hope so. We could use more of the drama and interest they bring. The expected protests against them failed to appear after the 200. Does that mean everything’s cool? Not at all. All the problems of AMA roadracing remain as they were, with the rogue pace car added for extra flavor. Is there hope? You bet, and it depends on what all the unpredictable conspirators and other interested parties do next. Put on your trench coat and turn down the brim of your fedora. Who knows? It might even be fun.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe New Guy

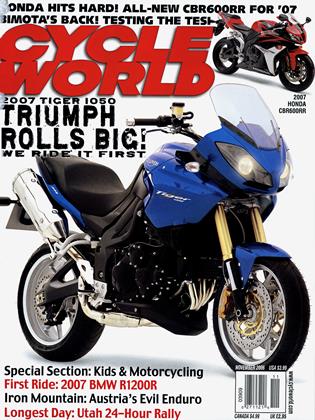

November 2006 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsReturn of the Scrambler

November 2006 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBack To Nature

November 2006 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2006 -

Roundup

RoundupBoulevard Bruiser

November 2006 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupComing Soon: Monster 695

November 2006 By Bruno Deprato