Return of the Scrambler

LEANINGS

Peter Egan

DID YOU EVER HAVE ONE OF THOSE WEIRD days where cosmic chance repeats itself and you hear three different people use the word “Abyssinian?”

That’s kind of how my whole month is going, but in this case the magic word has been “Scrambler.”

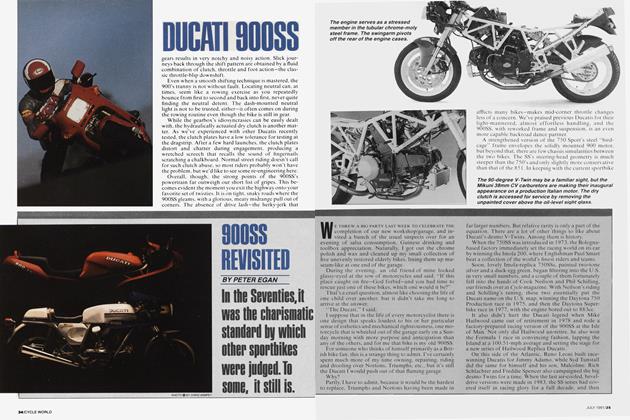

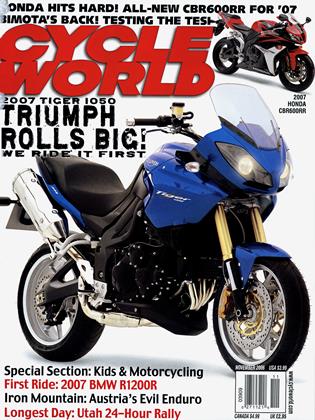

A few weeks ago, you see, I was invited out to California to write the Cycle World story on Triumph’s new 900 Scrambler, which takes its inspiration from a long line of Trophy Twins, the bikes that dominated desert and enduro racing for much of the Fifties and Sixties.

To brush up on a little history for this assignment, I walked over to my office bookshelves and pulled out all my Triumph books, which are legion. In fact, their absence made my bookcase look like a boxer with his front teeth knocked out.

My favorites are Triumph in America by Lindsay Brooke & David Gaylin, and Triumph Racing Motorcycles in America, a solo effort by Brooke. These volumes are as well-thumbed and worn as Pat Robertson’s two favorite Bibles.

For a few evenings I immersed myself in these books again, then went out to my mildew-scented Wall of Ancient Motorcycle Magazines on “what used to be a perfectly nice sun porch” and dug out all the old road tests I could find on Triumph scramblers from the Sixties. While searching, I also paged through the magazines, looking at ads, articles and other road tests.

It reminded me once again that this really was the era of the street-scrambler. Every manufacturer had one-or many-in the lineup. Most motorcycle companies built a scrambler in every single displacement category-all the way down to 50cc.

Some were attempts to make real dualsport bikes, while others were just trendy styling exercises with high pipes, knobbies and braced handlebars slapped on a streetbike.

It’s hard to imagine, for instance, that anyone took the scrambler version of the peaky-fast Suzuki X6 Hustler very far off road. Yet it’s that high-pipe version I remember best, probably because there were so many around. And it looked cool.

Some scramblers you wouldn’t suspect of having great off-road competence did surprisingly well. A fearsome CW-sponsored Norton P-11 scrambler ridden by Jerry Platt and Vem Hancock finished 18th overall in the first Baja 1000 in 1967, despite a devastating nighttime crash and lengthy repairs.

And a Honda CL350 won the 1968 Baja 1000 outright! Never mind that it was breathed upon by Long Beach Honda and ridden by the talented duo of Larry Berquist and Gary Preston; it was still based on the all-purpose street-scrambler you could buy at your local Honda store.

I should confess here that one of the tragedies of my young life was that I went through this whole era without owning a scrambler. As an impoverished student, I felt lucky to have any bike at all, and bought my first three motorcycles because, like Mt. Everest, they were there. Also cheap.

But the bike brochures taped to the wall above my desk, as I drudged through highschool homework, were all scramblers. Mainly, the Honda 160 and 305 Scramblers, high-pipe Triumph, and the exquisite (but reputedly troublesome) BSA 441 Victor.

What was the appeal here?

Well, what these bikes had going for them were romance and versatility.

There was-and is-something especially appealing about being able to climb on a bike and think you might go almost anywhere on Earth (okay, anywhere in your own hemisphere) right from your garage. That notion might have been largely illusory-as a teenager, you probably weren’t going to Peru-but there were dirt and gravel roads right at the edge of town, and you could head out into the country and explore them. The compact size of most of these bikes, along with “trials universal” tires and wide bars, made that prospect not only possible, but inviting.

The racing connection helped, too, with all those pictures of Ekins, McQueen, Mulder et al bounding through the desert. In this respect, street-scramblers were a perfect expression of the impulsive, slightly reckless mood of the times. Sliding and jumping were much admired, fatalism rampant.

The popularity of the general, allpurpose dirt/streetbike gradually faded, probably about the time the Plonda CB750 Four took a fork in the trail marked “fast, heavy Superbike.” You could make a scrambler out of a roadgoing Norton 750 or Triumph 650, but the Honda 750 was hopeless in that regard. As was the Kawasaki 900 or Triumph Triple.

Meanwhile, light, street-legal bikes like the 250cc two-stroke Yamaha DT-1 developed into much better dirtbikes than the average street-scrambler had been. Specialization set in.

But now those forked roads seem to be converging again. BMW’s R1200GS is its best-selling bike; the new Ulysses is (in my opinion) the best Buell yet, and Husqvarna is making all its enduro bikes street-legal this year. And in my own garage are a KTM 950 Adventure and a Suzuki DR650.

Twenty-first century street-scramblers, you might say.

Or are they?

The bikes mentioned above (other than the Suzuki) are rather tall, heavy and expensive for the average street rider with a mildly adventurous streak. A bit too hardcore, perhaps.

Each of those traits takes a little fun out of the picture for someone who just wants to hop on and ride around, or make a quick run to the corner store. The big modem adventure-tourer lacks what you might call “casualness,” that inviting sense of accessibility and nimbleness that comes with smaller size. Beginning riders shy away from them, sensing too much seriousness and not enough simple pleasure. Or enough traditional style and finish.

Enter the Triumph Scrambler, modern on the inside, 1960s on the outside.

Maybe it’ll be much-copied, just as its ancestors were. All the way down to 50cc.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue