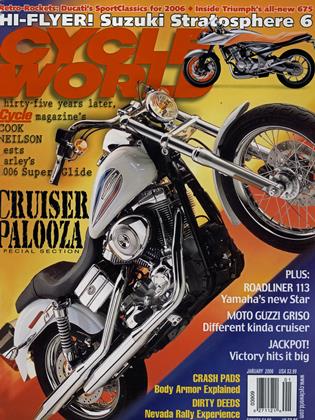

RETURN TO IMOLA

Riding the Ducati SportClassics

BRUNO DE PRATO

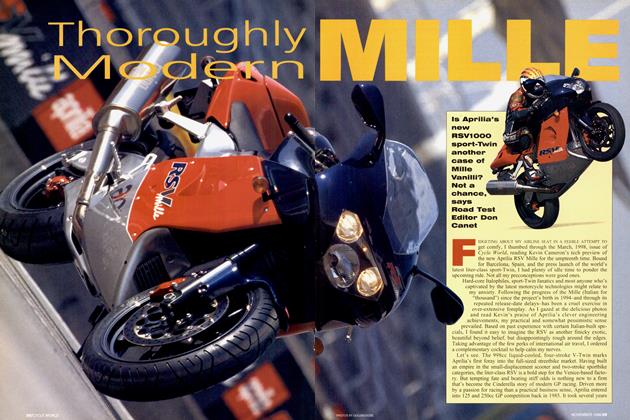

BACK TO IMOLA, WHERE IT ALL began 33 years ago with the first 200-miler. I could not think of a better place to acquaint myself with two of the new Ducati SportClassics: the Sport 1000 and the Paul Smart 1000 Limited Edition. The former pays homage to the 1973 750 Sport, while the latter celebrates the bike and the man who won the event that projected Ducati into a new dimension, giving the Bologna factory worldwide credibility in engineering and sporting performance. Ducati has won many races and titles, but none of those victories managed to duplicate the triumphal emotions generated by the one-two sweep at Imola in April, 1972.

Those emotions are carved into the hearts of an entire generation of motorcycle enthusiasts. Among them: Phil Schilling, Pierre Terblanche and, very humbly, yours truly. Schilling and I were there, and Tve had the pleasure of helping him with various Ducati restorations over the years. Terblanche’s way of loving old Ducatis is different: He re-thinks them for today.

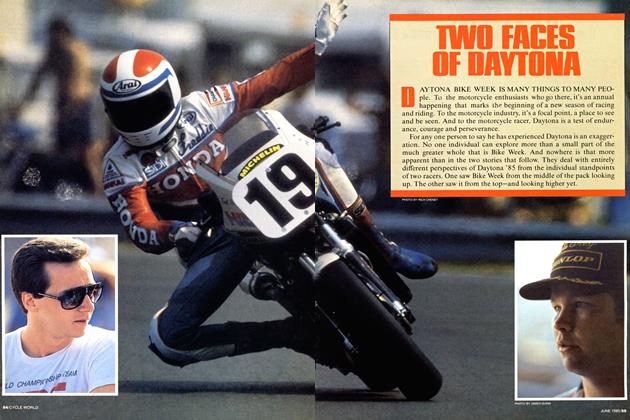

Imola never would have happened without Daytona. In 1970, the Daytona 200 was the biggest, most important motorcycle race in the world. To see what the fuss was all about, a delegation from the Italian motorcycle industry flew to Florida for the event. There was Ducati’s Dr. Fabio Taglioni,

Moto Guzzi CEO Michele Bianchi, Italian Motorcycle Federation president Ferruccio Colucci and Francesco “Checco” Costa, who had invested much of his life and personal capital to create the Imola track, which, at that time, was still partly based on roads open to public traffic.

Costa was a good friend of Dr. T, who owned a beautiful estate on a hillside overlooking the track. The two were impressed by what they saw in Daytona, and Dr. T. urged his friend to duplicate the event at Imola.

That summer, the 750GT first made its bellowing drone heard around Bologna. By

the end of ’71, with Costa planning to stage the inaugural Imola 200 the following spring, Taglioni was determined to make the race a big Ducati show to help boost

the image of his new Twins. It was widely reported at the time that Taglioni instructed the racing department to pick eight (other historians insist it was seven) bikes off the production line and modify their engines to get the best out of them. In reality, the bikes were likely built from the ground up, though based on production architecture.

The engine hop-up procedure was comprehensive-and precedent-setting. Of greatest importance here is the use of Desmodromic cylinder heads, which was the first application on a V-Twin and has since come to define Ducati. In modified form, the engines made more than 80 horsepower at nearly 9000 rpm.

Those were big numbers for the time, enough to keep BSA and Triumph Triples at bay (no factory Honda 750cc Fours or Yamaha 350cc two-strokes were entered in the race). Only Giacomo Agostini’s special race-framed MV

Agusta 750 Sport was an unknown. The production bike was a poor performer, but the potential was there, to be extracted by the world-conquering MV racing team lead by Arturo Magni.

The big question mark, then, was neither the competitiveness of the power nor the dynamic qualities of the chassis.

It was engine reliability. At the time, Ducati engines had pressed crankshafts, and failures were a concern. The problem stemmed from crank assemblies that were not properly trued. More-stringent quality control would have stamped out the problem, but it took a switch to solid cranks and cap-type rods turning on bulletproof Clevite 112 plain bearings to get the cranks straight for good. But that came years later with the Pantah.

One component was reliable: the main bearings. This is a little thing that I’m still proud of today. I was fresh out of college in South Carolina (aerospace engineering), and after a brief stint with Alfa Romeo’s aero-engines division, I was hired by Ducati in a multi-role position: public relations and product consultant. The ball-type radial main bearings used at the time would collapse because they could not take axial loads, a grossly overlooked problem even if the cranks had

been properly trued. As a result, Dr. T. had written off roller bearings because they could not take the high revs that the Singles and new Twin were capable of. So I

went back to my books and catalogs and came up with angular-contact, high-velocity ball bearings that were capable of taking very high loads, both axially and radially. They were very expensive, but proved so reliable that they are still on duty in current Twins.

For the race at Imola, all racing-department chief Franco Farne could do was take the cranks apart, fit special highperformance roller cages and classic twin-rib connecting rods machined from high-tensile steel billet, and then reassemble the whole thing with tender love and care.

On these machines, the rolling gear was pretty much stock, with the addition of dual Lockheed 290mm front brake discs and a 260mm rear, steering dampers, race-compound Dunlops and Marzocchi forks, the legendary 38mm offset axle designed by Dr. T. The bikes were wrapped in gel-coat metalflake-gray fairings and topped with 21 -liter fiberglass tanks sporting a clear band on both sides for checking fuel level at a glimpse. The frame was painted aqua.

Taglioni got his eight racers ready, then enlisted the riding

skills of ever-faithful Ducati ensign Bruno Spaggiari, test rider and part-time racer Ermanno Giuliano, and British specialists Allan Dunscombe and Paul Smart.

The next problem was how to transport all the bikes from Bologna to Imola. The solution came in the form a mobile showroom, a big truck with a glass-walled cargo compartment normally used to display motorcycles at local events around Italy. I remember watching Schilling’s jaw drop when he saw the glass truck full of race bikes roll into the Imola paddock. We looked at each other and then burst out laughing. Schilling was the only American journalist at Imola that year, and I had the privilege of helping him solve problems created by the organizers, who never expected media interest, let alone the managing editor from Cycle, then the number-one motorcycle magazine in the world, flying all the way from California to attend their event.

The rest is history. Smart and Spaggiari took the lead, tailed briefly by Agostini, who eventually retired with “electrical problems.” (Whenever an MV quit, the Magneti Marelli distributor was always blamed.) Mid-race, Smart and Spaggiari pitted together to refuel, and Smart got away first. Seeing his teammate sprint away, Spaggiari pushed aside his mechanics and blasted off. In doing so, he failed to get the last necessary drop of fuel. So Smart won, and Spaggiari came in second with a misfiring engine. Even

today, Spaggiari doesn’t talk about that second place.

The excitement generated by the Ducati sweep at Imola continued with the production 750SS and

900SS. These are the bikes that inspired Terblanche. His ability to re-interpret great Ducatis from the past was proven with the limited-edition Mike Hailwood Replica. In the case of the SportClassics, he skillfully mixed current technology and function with nostalgic styling that, rather than duplicate the originals, creates a visual feeling of closeness to them.

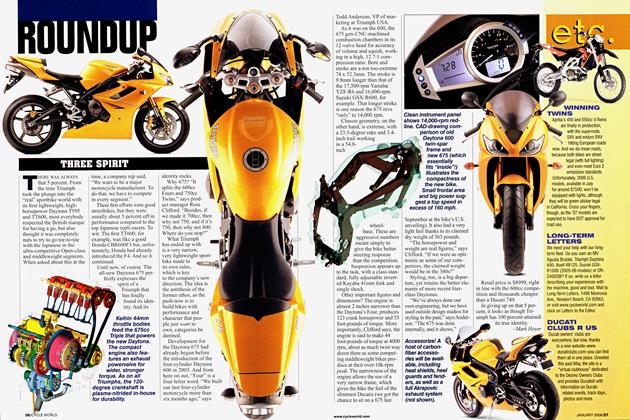

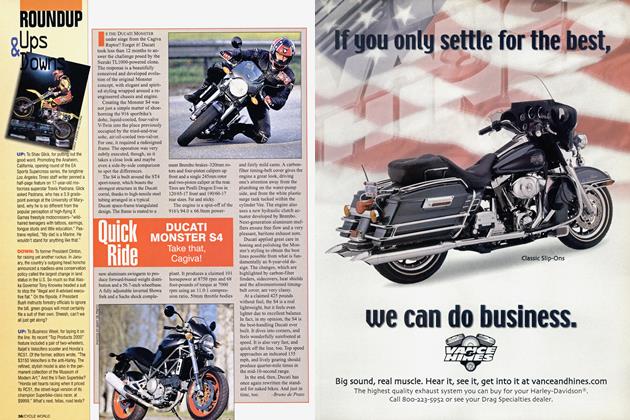

The Paul Smart 1000 Limited Edition and the Sport 1000 share the same frame and geometry. In fact, only a few basic components differentiate the two machines. Finely triangulated in the front section, the trellis-style frame is structurally very sophisticated and not used by other Ducatis. The same goes for the hydro-formed swingarm, which is a real work of art, reproducing the look of the 750/900SS models of the Seventies, but in a much more massive form, since the diameter of the tubing used for the arms has gone up considerably. A single shock, asymmetrically mounted on the left side, allows for right-side mounting of the over-under exhaust system. The Paul Smart features an inverted 43mm Öhlins fork, an Öhlins shock and a Sachs steering damper,

while the Sport gets a 43mm Marzocchi fork, a Sachs shock and no steering damper. Large-diameter, hollow axles are used at both ends.

Wheelbase is 56.1 inches, more than an inch longer than on the current Supersport 1000. The additional length was added to the rear, giving the SportClassics a 52/48 weight distribution and making for possibly the best-balanced Ducatis ever. Steering geometry is 24.0 degrees of rake, 4 inches of trail. Seat height is 32.5 inches. Claimed dry weight is low: 399 pounds for the Paul Smart and 395 for the Sport. Both bikes roll on elegant, 36-spoke, Excel aluminum-rimmed wheels, shod with Pirelli Diablo radiais in the latest sizes, a 120/70-17 front and a 180/55-17 rear. For a touch of nostalgia, the tread pattern is that of the old Phantom rear. Brakes are modern Brembos, with two semifloating 320mm rotors teamed with four-piston calipers up front. At the rear, a floating, single-piston caliper puts the squeeze on a 245mm rotor.

In a different time, Gigi Mengoli had to fight to keep the air-cooled V-Twin in Ducati’s inventory. I’m glad he didn’t give up, because for the SportClassics there was no other choice. With its modern electronics and fuel-injection, the 1000DS is far superior to the smaller-displacement, carbureted engines that powered the ’72 Imola stormers, even if peak horsepower-84 hp at 8000 rpm-is

only up slightly. With excellent drivability and shudder-free acceleration from as low as 2500 rpm, it’s the best air-cooled engine Ducati has ever pro-

duced, a glorious banger that delivers.

On the morning that Imola was available for our test, a thick, wet fog surrounded the whole hillside, leaving the tarmac treacherously slippery, with little grip anywhere.

The rain from the previous evening had stopped, though, so that was enough, and the Sport and Paul Smart sat ready in pit lane.

The Sport was a dark yellow in color, just like the one I used to ride three decades ago. It is best described as an

old-style café racer, with clip-on handlebars and rearset footpegs that deliver a racy, though not uncomfortable, riding position. The seat is supportive and the bike feels compact, due in large part to its light weight and easily managed engine. All this inspired a sense of togetherness with the bike and optimism over track conditions-until the engine’s generous torque curve and the rear tire’s lack of grip conspired to produce a sudden loss of stability! Braking demanded a safecracker’s touch on the lever, but accurate feedback made it easy to modulate power even when slowing from fairly high speeds.

The track was slow to dry, but by the time I switched to the Paul Smart, there were a few spots with decent grip. Rivazza Corner, for example, is pretty tricky, coming as it does at the end of a steep downhill run. Here, the more sophisticated suspension made itself known. The front end felt more precise, and the marginally extra weight and polar momentum generated by the half-fairing were imperceptible. In fact, the fairing makes for a more comfortable

riding experience, especially at higher speeds, and gave me the feeling of being transported through time, as if I were actually blasting past the screaming crowds as those two silver flashes did so many years ago. I missed the terrific thunder of the open megaphones, as the Paul Smart is more civilized than those old Desmos, yet the racer and the production bike still have much in common. The engine response is much the same, as is the acceleration and 140mph-plus top speed. There’s the same lovely feel of togetherness, too, just an extra touch of superior sophistication for the Paul Smart.

Rivazza’s semi-dry line was inviting, and I would have loved to dare a knee-grinding lean angle. But I conceded to the conditions, knowing that I might just as easily end up on my butt. Next time, though, look out... □