TRIUMPH TRACKER

A factorybacked project revives an old tradition

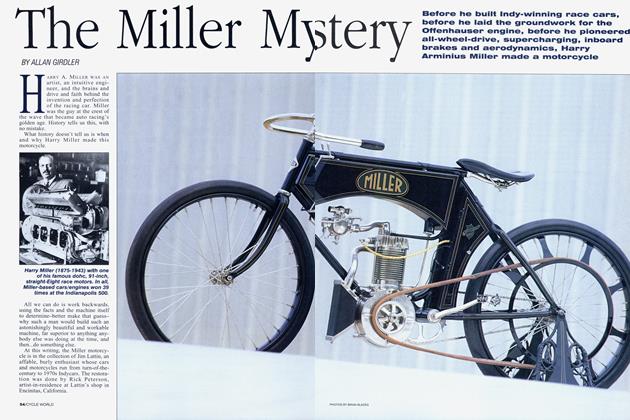

ALLAN GIRDLER

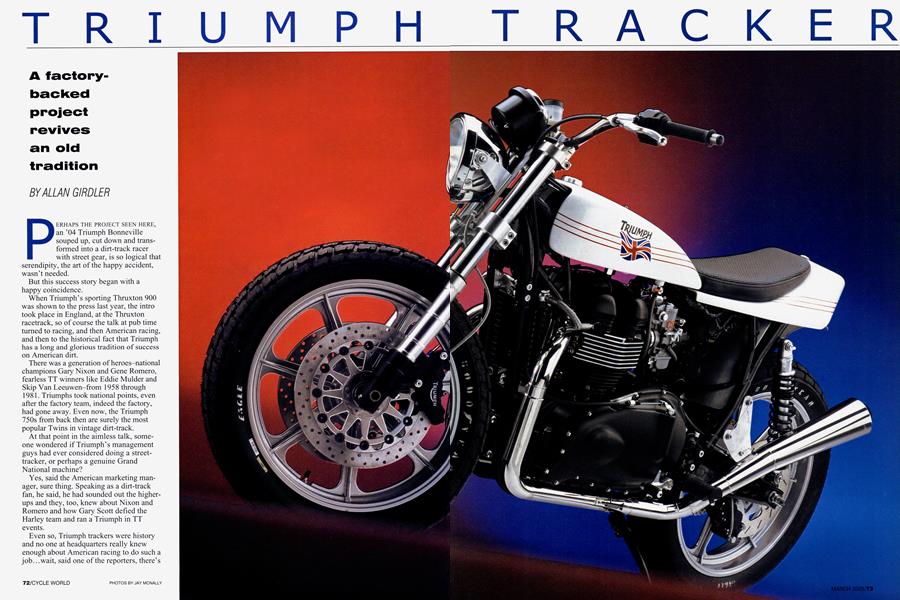

PERHAPS THE PROJECT SEEN HERE, an ’04 Triumph Bonneville souped up, cut down and transformed into a dirt-track racer with street gear, is so logical that serendipity, the art of the happy accident, wasn’t needed.

But this success story began with a happy coincidence.

When Triumph’s sporting Thruxton 900 was shown to the press last year, the intro took place in England, at the Thruxton racetrack, so of course the talk at pub time turned to racing, and then American racing, and then to the historical fact that Triumph has a long and glorious tradition of success on American dirt.

There was a generation of heroes-national champions Gary Nixon and Gene Romero, fearless TT winners like Eddie Mulder and Skip Van Leeuwen-from 1958 through 1981. Triumphs took national points, even after the factory team, indeed the factory, had gone away. Even now, the Triumph 750s from back then are surely the most popular Twins in vintage dirt-track.

At that point in the aimless talk, someone wondered if Triumph’s management guys had ever considered doing a streettracker, or perhaps a genuine Grand National machine?

Yes, said the American marketing manager, sure thing. Speaking as a dirt-track fan, he said, he had sounded out the higherups and they, too, knew about Nixon and Romero and how Gary Scott defied the Harley team and ran a Triumph in TT events.

Even so, Triumph trackers were history and no one at headquarters really knew enough about American racing to do such a job... wait, said one of the reporters, there’s a builder in California who’s just the man you need.

Richard Pollock, the reporter said. Does business under the name Mule Motorcycles. His day job in aerospace, Pollock is one of the craftsmen who takes the theories and computer work of the rocket scientists and turns them into hard parts, the metal and ceramic and unobtanium that become the actual space vehicles.

After hours, on his own time, Pollock builds showbikes, usually Harleys, for the Japanese, making him one of the few Americans to sell to, rather than buy from, that nation. And for a hobby he tunes and prepares Hondas and Yamahas and KTMs-quickly enough to take club class championships and miss making AMA fields by a fraction of a second.

Mule Motorcycles was clearly the perfect place for Triumph to have a street-tracker built, and as still another happy accident, the reporter had Mule’s phone m give to Triumph and the marketing man’s number to give to Pollock, and they came to terms. The result is what you see here. (Modesty and perhaps a shade of conflict of interest prevent any remarks about who the reporter was, eh? Just remember, you saw this project here first.)

Soon as the deal was done, Triumph delivered a new Bonneville and Pollock took it apart.

A stock Bonneville weighs about 475 pounds read) has a wheelbase of 58.5 inches and the 790cc en£ ers a claimed 61 crankshaft hp. Brisk, sufficient for use, not especially fast.

Pollock’s project got lots of help from D&D Pensacola, Florida, where the owners have becor for the current Bonneville’s sporting owners. D&D provided a big-bore kit, taking the engine out to 904cc, bigger even than the 865cc Thruxton option, and also sent along a hot camshaft, a sporting street grind if not a full-race.

The new carburetors are 35mm Keihin CRs, the roundslide model used by almost all Superbike builders back in the day who weren’t willing to spend four times the CR’s price for the fancier flat-slide version. For show, the carbs wear air horns, which wouldn’t be practical on the street, never mind flat-track.

The head was sent to Brian Sheridan, a top tuner in Superbike circles. He said the porting, the size of the valves and the form of the combustion chamber were good as they came stock, so they were mildly cleaned up and that was all. The Bonneville’s cases, barrels, the complete

lower end of the engine and the gearbox are more than ade-

quate stock and for racing, so no changes were made there, nor to the ignition.

Pollock “cut up a lot of pipe” to make the exhaust system. This was a challenge, and the result isn’t exactly in the dirttrack tradition. There wasn’t room for the classic high TT pipes, nor for mildly sweeping curves. The exhaust pipes are stainless-steel, 1.5 inches in diameter as they exit the head, growing to 1.85 inches below the frame and then to 2.0 inches at the megaphones, which have muffler cores.

The bends look a bit severe, and the tipped-up megaphones are more roadrace than flat-track, but they work and the look is surely current.

The engine, as a unit, was surprisingly light: Pollock could lug it around the shop, something not sensible with, say, a Harley XR-750.

The Bonneville frame was tidy, but had more investment castings, which are heavy, than expected. The front of the frame was usable. Pollock replaced the rear subframe with shorter, lighter and stronger chromoly tubes, which moved the seat, shocks and taillight mounts forward. The swingarm was shortened and beefed and braced, while neat touches like the stock drop-in chain adjusters were retained.

The Works Performance shocks are an inch longer than the stock units, to steepen the steering head’s rake and speed steering. The fork is from Triumph’s 955i Triple, 45mm diameter, with the stanchion tubes shortened by 1.5 inches. The billet clamps move the tubes closer to the steering stem for added trail. Nominal wheelbase, that is with the rear axle in the middle of its travel, is 55.5 inches. All the dimensional modifications are to put the bike close to flat-track standards. Actual wheel travel, front and rear, is unchanged.

The front brakes use the 955’s four-piston calipers with rotors from Kosman Racing. The rear brake has the stock master cylinder, a 10.5-inch rotor and two-piston caliper from A&A Racing. Handlebars are stainless-steel, dirt-track bend and width, from Ron Wood Racing.

Cast-magnesium wheels, in the classic 19-inch diameter, came from Sundance in Japan, and at $3300 a piece (!) are the most expensive parts on the list. They’re coated in a color and material known as Reflecta, which brightens in sunlight, no kidding.

Tires are Goodyear Eagle DT, labeled 27 x 7 and 27 x 7.5—for reasons lost to history, dirt-track tire labels and measurements don’t match; a 27 x 7 DT is 5 inches across and roughly compares to an older Pirelli 400 x 19.

After the frame and thus the whole machine was tipped forward, Pollock leveled the seat by reworking the mounting rails. The saddle itself began life as an aftermarket item, but Pollock didn’t want the routine Harley profile, so the rear was reshaped and enlarged to carry the taillights and license plate. The shape was done in foam, from which a mold was made and as a hint of future hopes, the seat seen here is one from a short production run.

At a glance, the fuel tank is classic Trackmaster. In fact, the fiberglass Trackmaster’s general profile was retained, but the tank, done by Racetech in Oxnard, California, is alloy, and carries a slosh more than two gallons.

This is a street-tracker so the bike retained the Bonneville’s headlight, one of the few stock pieces still in place. The rear light is one of those evergreen little units as seen on vintage British roadsters and older enduros. Most of the comprehensive electrical system is still in place, looking cluttered minus covers. Pollock plans to either reduce the bulk of the wiring loom or hide the tangle behind covers.

Paint for the deliberately skimpy bodywork is a slightly off-white pearlescent, with three red stripes as seen on the old team racers. The badge, a Union Jack flowing in partnership with the swooped R in the Triumph logo, was done by Dennis Wells of Uptown Cycle Design. It’s actually a painting, not a logo, although the Triumph execs who saw it, like it and it could become official.

And the math? A Thruxton weighs 472 pounds dry. Pollock estimates nearly 100 pounds have been pared off the Bonneville, so ready to go the project tracker should be close to 400 pounds, heavy for a dirt-track bike, light for the street.

Exact figures and a dyno run will have to wait. This project was ordered and funded by Triumph, so they have first call on the bike and their call is to show it at (modest pause here) Cycle World's International Motorcycle Shows, playing coast to coast from late ’04 to early ’05.

The tracker Bonneville is coming to a convention center near you, unless it’s already been when this appears. Either way, Pollock hopes to do some tidying up, and we’re hoping to wring it out.

Meanwhile, D&D Cycles, the makers of the speed stuff, has an AMA Grand National program in the works.. .and wouldn’t it be good to see Triumph back on track?

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

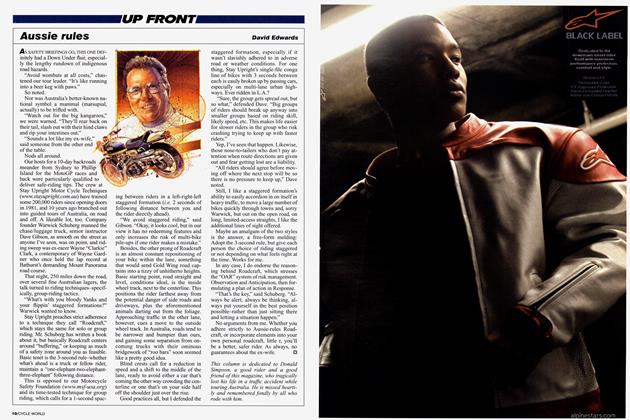

Up FrontAussie Rules

March 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOn the Trail of the Mighty One

March 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTelephone Teams

March 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

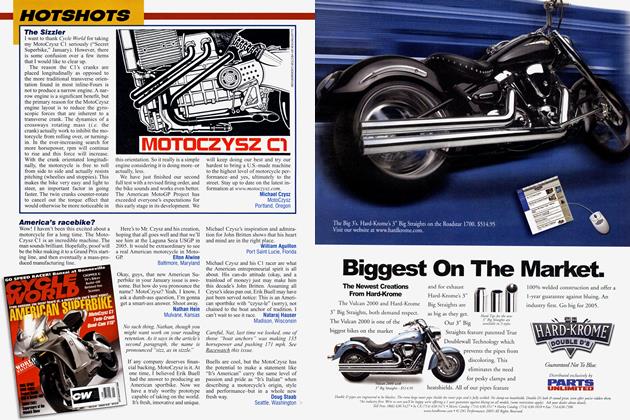

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2005 -

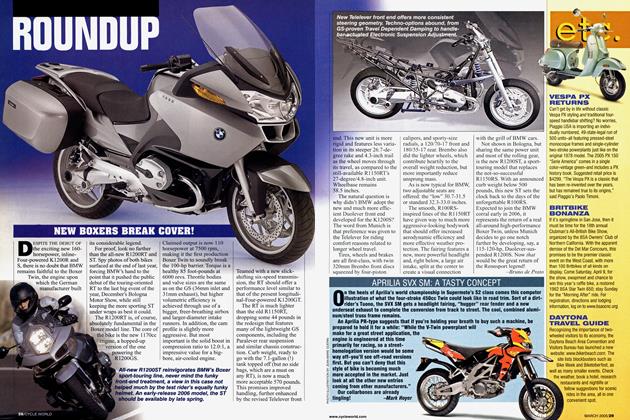

Roundup

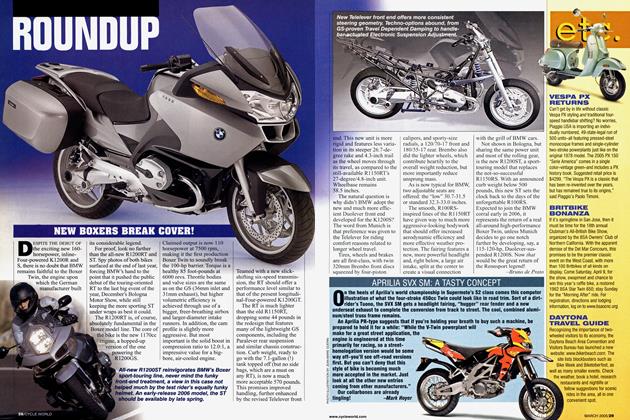

RoundupNew Boxers Break Cover!

March 2005 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Svx Sm: A Tasty Concept

March 2005 By Mark Hoyer