RACE WATCH

THE GIFT OF SPEED

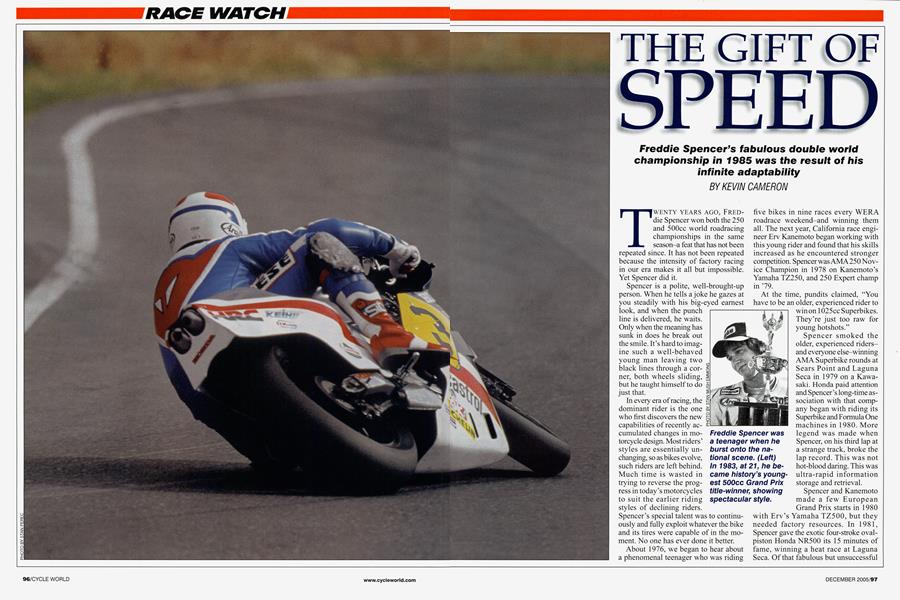

Freddie Spencer’s fabulous double world championship in 1985 was the result of his infinite adaptability

KEVIN CAMERON

TWENTY YEARS AGO, FREDdie Spencer won both the 250 and 500cc world roadracing championships in the same season—a feat that has not been repeated since. It has not been repeated because the intensity of factory racing in our era makes it all but impossible. Yet Spencer did it.

Spencer is a polite, well-brought-up person. When he tells a joke he gazes at you steadily with his big-eyed earnest look, and when the punch line is delivered, he waits.

Only when the meaning has sunk in does he break out the smile. It’s hard to imagine such a well-behaved young man leaving two black lines through a corner, both wheels sliding, but he taught himself to do just that.

In every era of racing, the dominant rider is the one who first discovers the new capabilities of recently accumulated changes in motorcycle design. Most riders’ styles are essentially unchanging, so as bikes evolve, such riders are left behind.

Much time is wasted in trying to reverse the progress in today’s motorcycles to suit the earlier riding styles of declining riders.

Spencer’s special talent was to continuously and fully exploit whatever the bike and its tires were capable of in the moment. No one has ever done it better.

About 1976, we began to hear about a phenomenal teenager who was riding five bikes in nine races every WERA roadrace weekend-and winning them all. The next year, California race engineer Erv Kanemoto began working with this young rider and found that his skills increased as he encountered stronger competition. Spencer was AMA 250 Novice Champion in 1978 on Kanemoto’s Yamaha TZ250, and 250 Expert champ in ’79.

At the time, pundits claimed, “You have to be an older, experienced rider to win on I025cc Superbikes. They’re just too raw for young hotshots.”

Spencer smoked the older, experienced ridersand everyone else-winning AMA Superbike rounds at Sears Point and Laguna Seca in 1979 on a Kawasaki. Honda paid attention and Spencer’s long-time association with that company began with riding its Superbike and Formula One machines in 1980. More legend was made when Spencer, on his third lap at a strange track, broke the lap record. This was not hot-blood daring. This was ultra-rapid information storage and retrieval.

Spencer and Kanemoto made a few European Grand Prix starts in 1980 with Erv’s Yamaha TZ500, but they needed factory resources. In 1981, Spencer gave the exotic four-stroke ovalpiston Honda NR500 its 15 minutes of fame, winning a heat race at Laguna Seca. Of that fabulous but unsuccessful engineering project Spencer said, “The heat.. .that and the bulk of the engine.. .it couldn’t sit far enough forward. It had no torque, so you had to anticipate with the throttle. The British GP at Silverstone was next and I knew it wasn’t going to work there.”

Nevertheless, Spencer put the NR, described by another rider as “heavy as lead,” into fifth before it stopped running. Honda digested embarrassment and accepted that pure engineering wasn’t enough in racing. Setting aside its fourstroke pride, Honda put in the back-up program-a two-stroke Triple-for Freddie’s first lull 500cc GP season in 1982.

“When Erv first saw that thing...”, Freddie began, then let the words hang.

What they saw was like three 166cc reed-valve motocross engines on a single crank. It was nothing like the mighty and dominant 140-horsepower disc-valve square-Fours of Suzuki and Yamaha. Yet Spencer instantly learned to ride it in spite of the novelty of life in Europe, despite splitting practice between machine setup and learning new circuits. By the seventh race, he had it figured out and won-aged only 20. The year also brought four mechanical DNFs and a crash in the rain. His boy-next-door cheerfulness was bulletproof, as he won the next-to-last race as well. In his first full season in Europe, he’d finished third in the 500cc championship. I asked him how he handled the strangeness of Europe, the lack of familiar surroundings.

“Europe got easier after we got the motorhome,” he said. “But I was so focused on what we had to do that I mostly didn’t notice.”

As racebikes became more powerful, their acceleration made them harder to steer off comers-what riders today call “completing the comer.” Engineers responded by moving engines forward, restoring the load needed to keep the front tire steering. Most riders responded to this trend by entering turns more cautiously, as extra front tire load easily becomes overload, causing a front-end tuck from diminished grip. For a combination of reasons, Spencer was uniquely prepared to turn this problem into an opportunity.

“I was, I don’t know, 14 or 15, at a dirt-track near Tulsa,” he said. “I was riding a 500 Single and the other guys mostly had 750s. I’d ride into the turn faster and faster, and then the front would start to tuck. I played with it a little and I found that when that happened, if I picked up the throttle, lifted up the bike and got the back tire moving, the front would grip again. I played with it some more until I could almost go all the way around that track wide open.

“You had to do it just right, though,” he went on. “If you didn’t, you’d end up losing both ends. I finished maybe third or something that day. But I took home something that was worth a lot more than a win.”

A year or two later, Spencer was on a Kanemoto Yamaha 250 at Loudon, New Hampshire, and decided to try on pavement what had worked so well on dirt. He could do it, entering turns at a speed that would for other riders mean loss of front grip and a certain crash. Picking up the throttle transferred some load from the small, overloaded front tire to the larger rear. The front would then grip again and Spencer could apply more power to get the back tire sideways to increase his turning power. The result was a super-fast corner entry, a high comer speed and a quick transition back to acceleration-the condition in which front-heavy bikes are most stable because it puts most of the load on the big rear tire. What the onlooker heard was Spencer, cracking open the throttle the instant the bike reached full lean-earlier than anyone.

When Spencer rode Honda’s 1982 NS500 two-stroke GP bike this way, even highly experienced observers attributed his speed off comers to “tremendous reed-valve acceleration.” Yet that early Triple actually had ultra-narrow power from 9800-11,000 rpm-and just 108 hp. Powerband width comes from pipes and porting. Reeds just obey orders from the moving air. At Honda’s early state of two-stroke knowledge, this was the best the engineers could do. They were learning.

Spencer didn’t have a choice. If he wanted to lead on this motorcycle, this was how he had to ride. “Top speed was pretty good,” he remembered. “But it didn’t have any midrange, so if I didn’t keep a high comer speed, I couldn’t hold on to those (Yamaha, Suzuki) four-cylinders.”

Kanemoto was a pioneer in forward weight placement. Knowing that powerful bikes “pushed” when accelerating off turns, he’d included a completely adjustable steering head on the Suzuki 750 he built for Gary Nixon in 1974. It confirmed his conclusion that rake and trail changes can’t make a bike steer off corners. Only adequate front tire load can do that. To achieve this load, engine and rider had to be moved forward, just as Velocette had done in 1935 and just as Rex McCandless had done for Norton in 1950. Spencer and Kanemoto brought this message to Honda just as the company was switching from the 18,500-rpm four-stroke NR500 to the motocross department’s two-stroke GP project-the NS3. Honda is ruled today by the very men who designed the NR and the NS. Then, they were up-and-coming engineers.

“That was really my bike,” Spencer told me, meaning that it was made to suit his abilities alone. “Takazumi Katayama won one race in the rain on it.” Otherwise, Freddie was the only man to win on it. It was his bike. In fact, other riders on the NS500 tended to lose the front end, and there were some serious accidents.

Even Spencer’s ability to ride a nopowerband bike was a gift of circumstance. At the time Kanemoto began working with Spencer in the U.S., his 250cc engine produced all its power up high, with little midrange. With characteristic adaptability, Spencer mastered it-and the similar, but much more powerful TZ750 soon after. When the NS3 arrived in 1982, he was ready.

Meanwhile, in 1980 Erv and Freddie went to the Trans-Atlantic Match Races with the Yamaha 750-a flexing, armstretching machine whose torque nearly doubled at 9300 rpm, its power peaking at 10,300. Spencer built up a 60-second lead at Daytona on this bike, only to lose a big-end bearing just before the second gas stop. Spencer and Kanemoto absorbed the setback. In England, the other riders-established international stars-were on up-to-date 500s with better suspension and smoother, non-exploding powerbands. Seeing himself and Kanemoto as “just guys in a little rental van,” Spencer felt invisible. During practice he told Kanemoto that maybe they didn’t belong there. Erv replied, “There’ll be days like this.” Even if you don’t have an edge, you race with what you have. Spencer raced, winning the two races at Brands Hatch, beating Kenny Roberts and Barry Sheene in the process.

“That was a wonderful feeling,” Spencer said, grinning and savoring the experience anew. “Everyone was shocked but me. I knew I was in the right place. The attitude around us was suddenly, ‘Who are these guys?’

“Do you know Brands?” he asked me. “There’s this turn out in the back. I got maybe 50 or 100 yards off that turn and then I looked back. I could see the tum and I could see the approach to it, and there was no one there.”

In 1999, when Mick Doohan retired, I described to him Spencer’s comerentry style of using the throttle to relieve front tire overload. Doohan’s reply was, “You can ride that way. I’ve ridden that way. But you can’t do it all day long.” Spencer did.

On another occasion, I was talking with Roberts, years after both he and Spencer had retired. I made some reference to Freddie’s style and Kenny, always competitive, hotly cut me off. “Freddie didn’t have a style. He just coped.”

There’s some truth there. When Spencer and Kanemoto went to Brazil for preseason three-cylinder testing, Erv brought a radar gun to measure comer speed. After a couple of tests, he put it away. Freddie’s comer speed was just as high no matter what combination of chassis, fork, tires or swingarm was on the bike. The only real variable Kanemoto could find was the amount of sweat in Spencer’s helmet. Some setups made him work harder than others.

Erv then said to Mr. Oguma, Honda’s famously blunt team manager, “Do you know the word ‘compensation?’”

Spencer’s ability to instantly adapt to new conditions was the opposite of a traditional rider style. He adapted to the machine and to the moment, so in that sense what Roberts said was true: He had no riding style.

“At the end of a race, your tires are gone, your brakes are gone and you have to find ways to ride what you have left,” Spencer described to me. Despite this, just like Valentino Rossi today, Freddie’s fastest lap often came at the end of a GR When I proposed to him that this was the legacy of his father’s energy in preparing so many bikes for him to ride in so many WERA races, he exclaimed, “Absolutely! That’s how I learned!”

Today, engineering experience provides near-limitless combinations for use in machine setup. A rider can now expect his crew to adapt the machine to his style, rather than adapting his style to the machine. This seems proper because engineering exists to serve human needs. Then we remember that the machine, its brakes and its tires change throughout the race. If the rider cannot adapt to such changes as they come, lap times will suffer.

As the writers of the GP annual Motocourse put it, “1983 will be remembered as a classic confrontation between two racing talents that put everyone else completely in the shade.” Spencer won most of the early races, Roberts won four out of the last five and in between they traded DNFs and placings.

“Kenny and I were forced to ride the way we did by the differences in the bikes we rode,” Spencer acknowledged. “Sometimes our lines would cross.”

The reed-valve Honda gave Spencer quicker push starts, but the Yamaha’s wider torque allowed Roberts to slide big sweepers that Freddie had to break down into two comers, each placed to make use of the Honda’s narrow torque peak. Kenny’s preference for a “backmotor” bike with a more rearward center of gravity made his machinery light on the front and wheelie-prone-but more capable while braking. Spencer’s frontheavy NS was happy on super-early throttle in comers, keeping comer speed high. The Spencer/Roberts battles of 1983 have been called the greatest ever seen in GP racing.

The duel came down to the last two races, with the celebrated and often-described “off-road excursion” at the Swedish GP, of which Freddie says today, “You know, in Sweden, we never touched.” Both riders ran off and Spencer regained the track first, winning and putting himself in position to win the title at the last race by finishing second.

“Kenny would never say ‘congratulations,’” he said. “But on the podium he did say, T gave it everything I had.’” Spencer also revealed other concerns on that day. First, he said, “I wanted to beat Hailwood’s record-to be the youngest GP champion. And we knew that we had to win to keep Honda in the game.” Luck, that sum of immeasurables, is subject to change without notice. In the first race of 1984, at South Africa, Spencer set pole and then a carbon-fiber wheel broke. Eddie Lawson won. Spencer came back to win Misano but a broken foot at Donington sidelined him for the Spanish race. He won five races in all to Lawson’s four, but finished fourth in the championship to his new rival. Lawson was always there, maybe a quarter of a second behind in qualifying, always studying and working, grinding his way ever closer, a personal nemesis.

What is broken can be mended. Spencer had bounced back from misfortune or failure many times before. In 1985, Freddie not only won seven 500cc races but took the 250cc title as well. These were hard-fought, on-the-limit races and he won them one after another. Yet Lawson was a constant fixture, his relentless intensity burning a way forward. At a camera’s distance, Spencer’s ’85 season was seamless excellence, but people close to him knew he’d had to dig very deep again and again. The 11th race, held in Sweden, would be his last-ever GP win.

It wasn’t for lack of trying, but things got in his way now and nothing worked. Racing is cruel, always asking the uncaring question, “Yes, but what have you done lately?” Comebacks didn’t work, save for a few rides in AMA Superbike, where his old fluidity was evident but without some magical element. Fans are cruel, too. The public imagine a man into a hero, then blame him when he remains a man. Thus began the exile of Freddie Spencer-a time of intractable wrist problems, missed starts, blown-out contact lenses-the dark reverse side of seamless success. This time, it seemed, there was no mending what was broken.

What happened? Spencer did things that no other man could do as consistently or as well, but he found that he couldn’t do them forever. Should that surprise or disappoint us? Spencer’s reservoir of talent was wide and deep, but he poured it fast and generously, and we were fascinated. I asked him about this, citing something Roberts said years earlier about Randy Mamola: “People are saying he’ll have this long career because he’s started so young. But from what I’ve seen, a man gets 10 years in this sport. Then that’s it— something gets used up.”

Racing isn’t a video game. Like infantry combat, it has possible consequences no sane person can ignore. All people are changed by chronic exposure to extreme risk. Spencer’s rare adaptability kept him magically safe on the strange bubblelike surface that separates possible from impossible. Yet even the hardest soldiers, decorated heroes like Audie Murphy, know there are limits.

Freddie replied, “Yes, I think something does.. .get used up.”

With a faraway look he added, “But you know, I think if there hadn’t been those accidents and problems I could’ve carried right on.”

Today Freddie Spencer operates his racing school at Las Vegas Motor Speedway and enjoys family life with his wife and two children. He’s still smooth and fast on a motorcycle, and he can explain what it takes to go fast. He survived the 100-mph knee saves and the sixth-gear front-end tucks while accomplishing great things that we all admire. He’s in from the cold.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

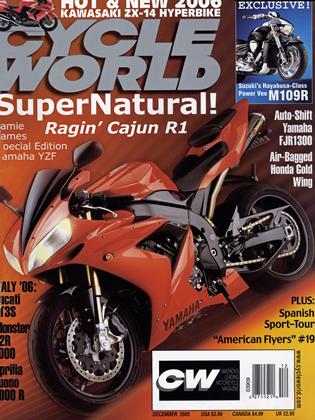

Up Front

Up FrontMiscellany

December 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsKing of the World

December 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCFire, Misfire

December 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2005 -

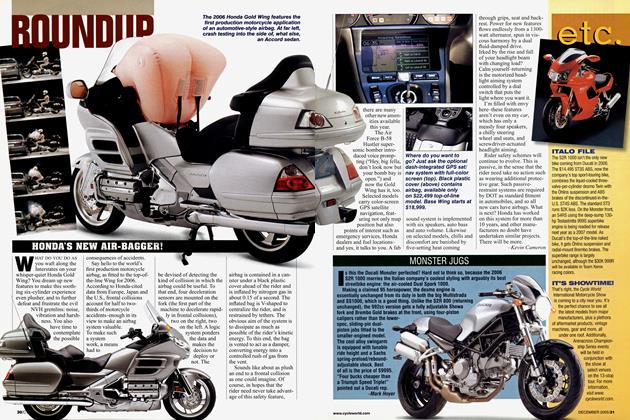

Roundup

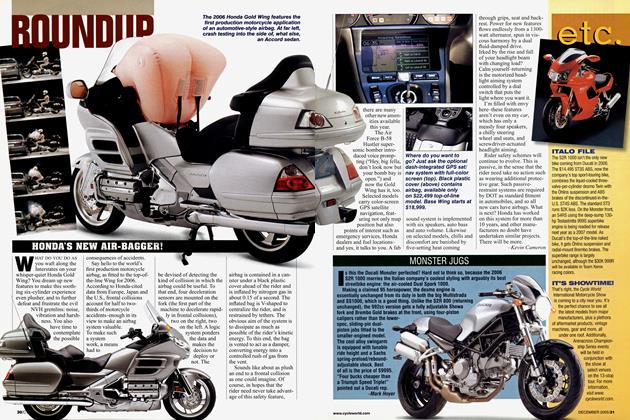

RoundupHonda's New Air-Bagger!

December 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupMonster Jugs

December 2005 By Mark Hoyer