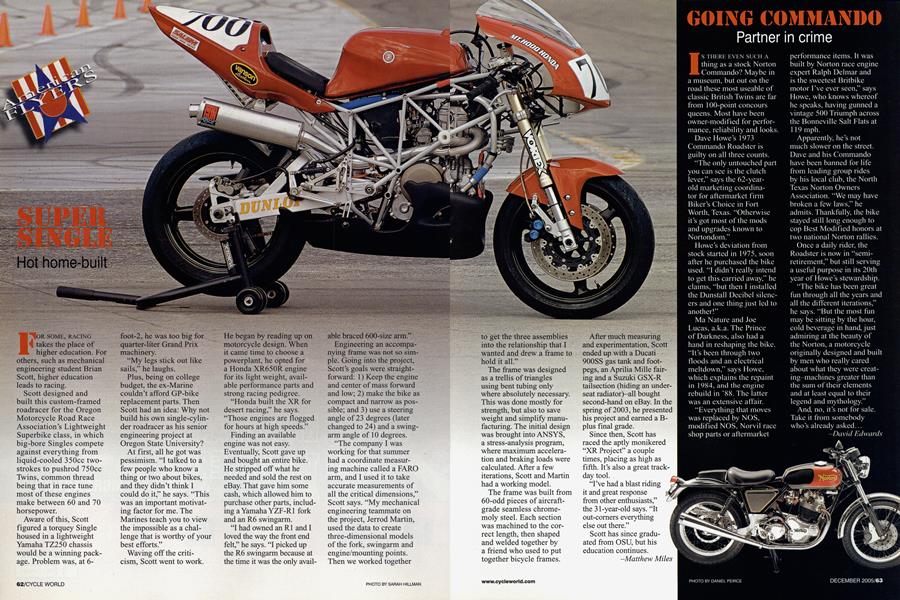

SUPER SINGLE

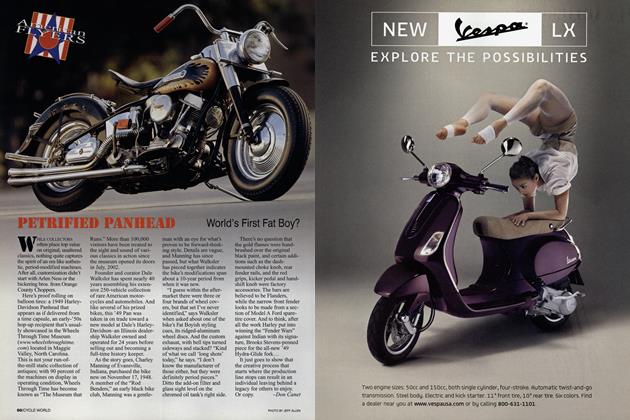

American FLYERS

Hot home-built

FOR SOME, RACING takes the place of higher education. For others, such as mechanical engineering student Brian Scott, higher education leads to racing.

Scott designed and built this custom-framed roadracer for the Oregon Motorcycle Road Race Association’s Lightweight Superbike class, in which big-bore Singles compete against everything from liquid-cooled 350cc two-strokes to pushrod 750cc Twins, common thread being that in race tune most of these engines make between 60 and 70 horsepower.

Aware of this, Scott figured a torquey Single housed in a lightweight Yamaha TZ250 chassis would be a winning package. Problem was, at 6foot-2, he was too big for quarter-liter Grand Prix machinery.

“My legs stick out like sails,” he laughs.

Plus, being on college budget, the ex-Marine couldn’t afford GP-bike replacement parts. Then Scott had an idea: Why not build his own single-cylinder roadracer as his senior engineering project at Oregon State University?

At first, all he got was pessimism. “I talked to a few people who know a thing or two about bikes, and they didn’t think I could do it,” he says. “This was an important motivating factor for me. The Marines teach you to view the impossible as a challenge that is worthy of your best efforts.”

Waving off the criticism, Scott went to work. He began by reading up on motorcycle design. When it came time to choose a powerplant, he opted for a Honda XR650R engine for its light weight, available performance parts and strong racing pedigree.

“Honda built the XR for desert racing,” he says. “Those engines are flogged for hours at high speeds.”

Finding an available engine was not easy. Eventually, Scott gave up and bought an entire bike.

He stripped off what he needed and sold the rest on eBay. That gave him some cash, which allowed him to purchase other parts, including a Yamaha YZF-R1 fork and an R6 swingarm.

“I had owned an RI and I loved the way the front end felt,” he says. “I picked up the R6 swingarm because at the time it was the only available braced 600-size arm.”

Engineering an accompanying frame was not so simple. Going into the project, Scott’s goals were straightforward: 1) Keep the engine and center of mass forward and low; 2) make the bike as compact and narrow as possible; and 3) use a steering angle of 23 degrees (later changed to 24) and a swingarm angle of 10 degrees.

“The company I was working for that summer had a coordinate measuring machine called a FARO arm, and I used it to take accurate measurements of all the critical dimensions,” Scott says. “My mechanical engineering teammate on the project, Jerrod Martin, used the data to create three-dimensional models of the fork, swingarm and engine/mounting points. Then we worked together to get the three assemblies into the relationship that I wanted and drew a frame to hold it all.”

The frame was designed as a trellis of triangles using bent tubing only where absolutely necessary. This was done mostly for strength, but also to save weight and simplify manufacturing. The initial design was brought into ANSYS, a stress-analysis program, where maximum acceleration and braking loads were calculated. After a few iterations, Scott and Martin had a working model.

The frame was built from 60-odd pieces of aircraftgrade seamless chromemoly steel. Each section was machined to the correct length, then shaped and welded together by a friend who used to put together bicycle frames.

After much measuring and experimentation, Scott ended up with a Ducati 900SS gas tank and footpegs, an Aprilia Mille fairing and a Suzuki GSX-R tailsection (hiding an underseat radiatorj-all bought second-hand on eBay. In the spring of 2003, he presented his project and earned a Bplus final grade.

Since then, Scott has raced the aptly monikered “XR Project” a couple times, placing as high as fifth. It’s also a great trackday tool. .

“I’ve had a blast riding it and great response from other enthusiasts,” the 31-year-old says. “It out-comers everything else out there.”

Scott has since graduated from OSU, but his education continues.

-Matthew Miles

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMiscellany

December 2005 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsKing of the World

December 2005 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCFire, Misfire

December 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

December 2005 -

Roundup

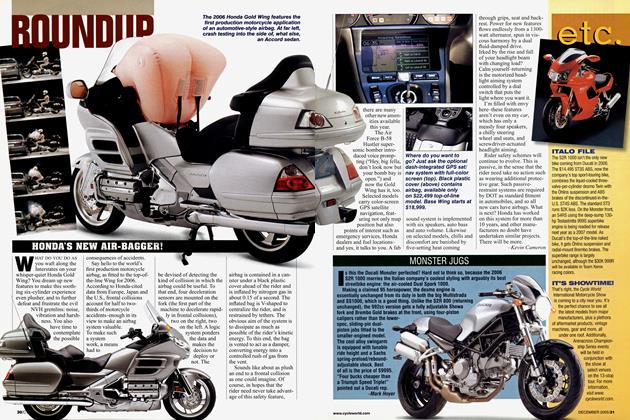

RoundupHonda's New Air-Bagger!

December 2005 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupMonster Jugs

December 2005 By Mark Hoyer