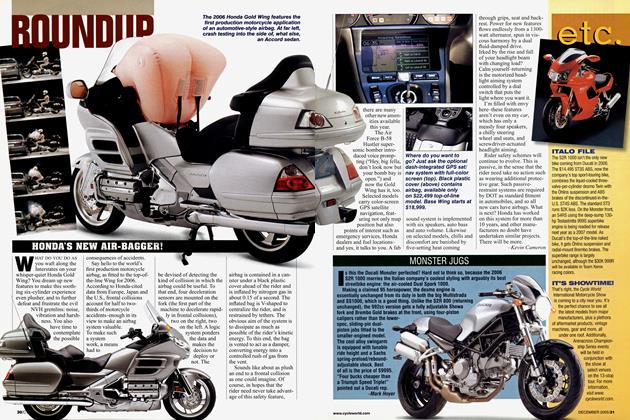

THE NEW NORTON

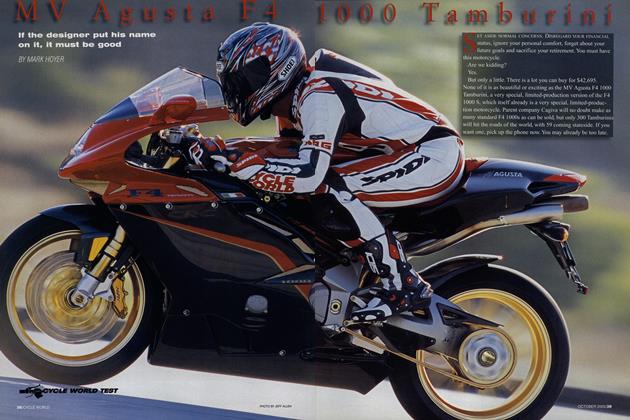

STARTING A MOTORCYCLE COMPANY IS BOTH ADMIRABLE and insane. History is littered with the snapped crankshafts, shattered dreams and broken men who have tried. Resurrections of storied old brands have come—and (Triumph aside) mostly gone.

And if you were ever to try to concoct the world’s Least Likely Resurrection Scenario, it would be that of Olde English bike-maker Norton being reborn in the New World-specifically Portland, Oregon-using a wholly new and proprietary motorcycle design by Kenny Dreer who, little more than five years ago, was restoring vintage bikes in his bam.

By 1999, though, his “restorations” had evolved into something more, essentially the remanufacturing of Commandos using more and more modem parts. At the end of the last century, we tested the first significantly upgraded Norton Twin turned out by Dreer’s company, known as Vintage Rebuilds at that time. It was the VR880 Sprint Special, and was as much Dreer as it was Norton, with most major systems very heavily modified or completely replaced. His bikes evolved further, to the point that ultimately only the cylinder heads and gearboxes were of original Norton manufacture. Frames, barrels, swingarms, suspension, brakes and wheels were all-new. So when we subtitled that ’99 road test, “A Norton for the Nineties.. .and beyond,” no one had any idea how prophetic that really was.

For here we are today, when Dreer & Co. have consolidated virtually all of the worldwide rights to the 106-yearold Norton name, and are on the cusp of producing for sale a real, all-new Norton Commando.

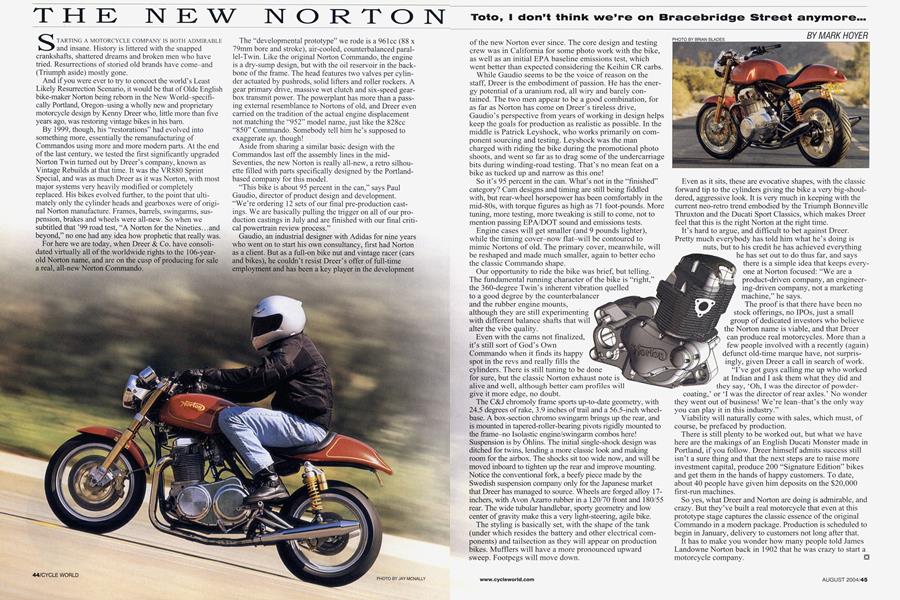

The “developmental prototype” we rode is a 961cc (88 x 79mm bore and stroke), air-cooled, counterbalanced parallel-Twin. Like the original Norton Commando, the engine is a dry-sump design, but with the oil reservoir in the backbone of the frame. The head features two valves per cylinder actuated by pushrods, solid lifters and roller rockers. A gear primary drive, massive wet clutch and six-speed gearbox transmit power. The powerplant has more than a passing external resemblance to Nortons of old, and Dreer even carried on the tradition of the actual engine displacement not matching the “952” model name, just like the 828cc “850” Commando. Somebody tell him he’s supposed to exaggerate up, though!

Aside from sharing a similar basic design with the Commandos last off the assembly lines in the midSeventies, the new Norton is really all-new, a retro silhouette filled with parts specifically designed by the Portlandbased company for this model.

“This bike is about 95 percent in the can,” says Paul Gaudio, director of product design and development. “We’re ordering 12 sets of our final pre-production castings. We are basically pulling the trigger on all of our production castings in July and are finished with our final critical powertrain review process.”

Gaudio, an industrial designer with Adidas for nine years who went on to start his own consultancy, first had Norton as a client. But as a full-on bike nut and vintage racer (cars and bikes), he couldn’t resist Dreer’s offer of full-time employment and has been a key player in the development of the new Norton ever since. The core design and testing crew was in California for some photo work with the bike, as well as an initial EPA baseline emissions test, which went better than expected considering the Keihin CR carbs.

Toto, I don't think we're on Bracebridge Street anymore...

MARK HOYER

While Gaudio seems to be the voice of reason on the staff, Dreer is the embodiment of passion. He has the energy potential of a uranium rod, all wiry and barely contained. The two men appear to be a good combination, for as far as Norton has come on Dreer’s tireless drive,

Gaudio’s perspective from years of working in design helps keep the goals for production as realistic as possible. In the middle is Patrick Leyshock, who works primarily on component sourcing and testing. Leyshock was the man charged with riding the bike during the promotional photo shoots, and went so far as to drag some of the undercarriage bits during winding-road testing. That’s no mean feat on a bike as tucked up and narrow as this one!

So it’s 95 percent in the can. What’s not in the “finished” category? Cam designs and timing are still being fiddled with, but rear-wheel horsepower has been comfortably in the mid-80s, with torque figures as high as 71 foot-pounds. More tuning, more testing, more tweaking is still to come, not to mention passing EPA/DOT sound and emissions tests.

Engine cases will get smaller (and 9 pounds lighter), while the timing cover-now flat-will be contoured to mimic Nortons of old. The primary cover, meanwhile, will be reshaped and made much smaller, again to better echo the classic Commando shape.

Our opportunity to ride the bike was brief, but telling. The fundamental running character of the bike is “right, the 360-degree Twin’s inherent vibration quelled to a good degree by the counterbalancer and the rubber engine mounts, although they are still experimenting with different balance shafts that will alter the vibe quality.

Even with the cams not finalized, it’s still sort of God’s Own Commando when it finds its happy spot in the revs and really fills the cylinders. There is still tuning to be done for sure, but the classic Norton exhaust note is alive and well, although better cam profiles will give it more edge, no doubt.

The C&J chromoly frame sports up-to-date geometry, with 24.5 degrees of rake, 3.9 inches of trail and a 56.5-inch wheelbase. A box-section chromo swingarm brings up the rear, and is mounted in tapered-roller-bearing pivots rigidly mounted to the frame-no Isolastic engine/swingarm combos here! Suspension is by Öhlins. The initial single-shock design was ditched for twins, lending a more classic look and making room for the airbox. The shocks sit too wide now, and will be moved inboard to tighten up the rear and improve mounting. Notice the conventional fork, a beefy piece made by the Swedish suspension company only for the Japanese market that Dreer has managed to source. Wheels are forged alloy 17inchers, with Avon Azarro rubber in a 120/70 front and 180/55 rear. The wide tubular handlebar, sporty geometry and low center of gravity make this a very light-steering, agile bike.

The styling is basically set, with the shape of the tank (under which resides the battery and other electrical components) and tailsection as they will appear on production bikes. Mufflers will have a more pronounced upward sweep. Footpegs will move down.

Even as it sits, these are evocative shapes, with the classic forward tip to the cylinders giving the bike a very big-shouldered, aggressive look. It is very much in keeping with the current neo-retro trend embodied by the Triumph Bonneville Thruxton and the Ducati Sport Classics, which makes Dreer feel that this is the right Norton at the right time.

It’s hard to argue, and difficult to bet against Dreer. Pretty much everybody has told him what he’s doing is nuts, but to his credit he has achieved everything he has set out to do thus far, and says there is a simple idea that keeps everyone at Norton focused: “We are a product-driven company, an engineering-driven company, not a marketing machine,” he says.

The proof is that there have been no stock offerings, no IPOs, just a small group of dedicated investors who believe the Norton name is viable, and that Dreer can produce real motorcycles. More than a few people involved with a recently (again) defunct old-time marque have, not surprisingly, given Dreer a call in search of work.

“I’ve got guys calling me up who worked at Indian and I ask them what they did and they say, ‘Oh, I was the director of powdercoating,’ or T was the director of rear axles.’ No wonder they went out of business! We’re lean-that’s the only way you can play it in this industry.”

Viability will naturally come with sales, which must, of course, be prefaced by production.

There is still plenty to be worked out, but what we have here are the makings of an English Ducati Monster made in Portland, if you follow. Dreer himself admits success still isn’t a sure thing and that the next steps are to raise more investment capital, produce 200 “Signature Edition” bikes and get them in the hands of happy customers. To date, about 40 people have given him deposits on the $20,000 first-run machines.

So yes, what Dreer and Norton are doing is admirable, and crazy. But they’ve built a real motorcycle that even at this prototype stage captures the classic essence of the original Commando in a modem package. Production is scheduled to begin in January, delivery to customers not long after that.

It has to make you wonder how many people told James Landowne Norton back in 1902 that he was crazy to start a motorcycle company.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue