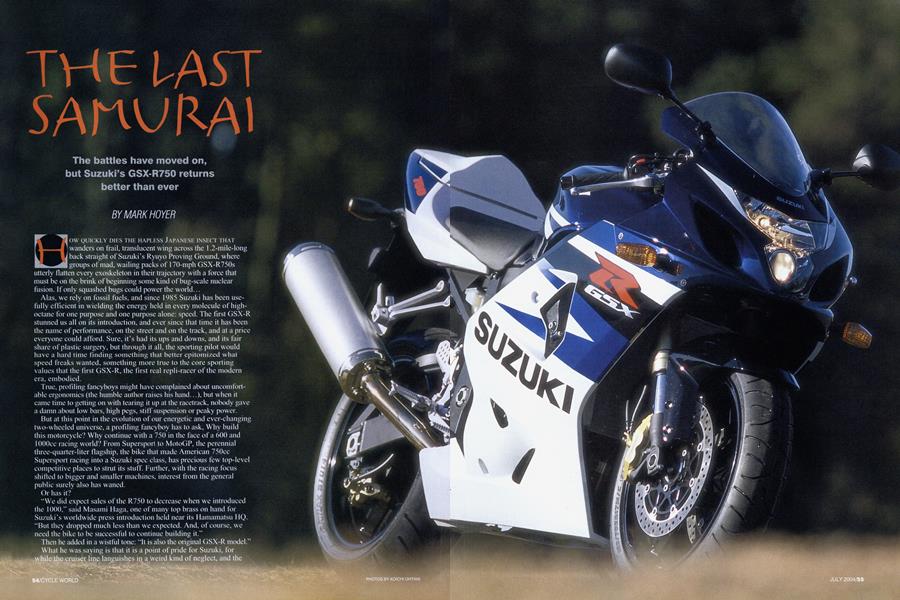

THE LAST SAMURAI

The battles have moved on, but Suzuki’s GSX-R750 returns better than ever

MARK HOYER

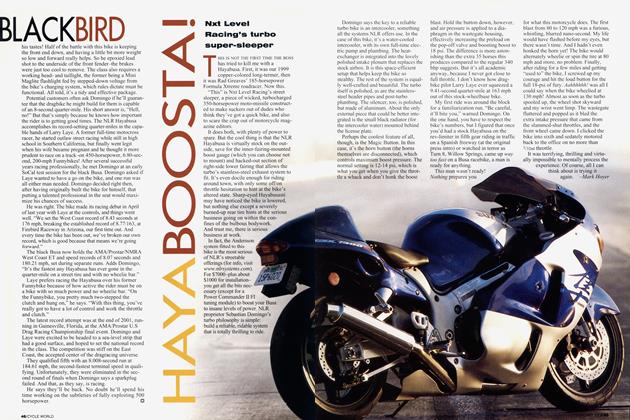

HOW QUICKLY DIES THE HAPLESS JAPANESE INSECT THAT wanders on frail, translucent wing across the 1.2-mile-long back straight of Suzuki’s Ryuyo Proving Ground, where groups of mad, wailing packs of 170-mph GSX-R750s utterly flatten every exoskeleton in their trajectory with a force that must be on the brink of beginning some kind of bug-scale nuclear fusion. If only squashed bugs could power the world...

Alas, we rely on fossil fuels, and since 1985 Suzuki has been usefully efficient in wielding the energy held in every molecule of highoctane for one purpose and one purpose alone: speed. The first GSX-R stunned us all on its introduction, and ever since that time it has been the name of performance, on the street and on the track, and at a price everyone could afford. Sure, it’s had its ups and downs, and its fair share of plastic surgery, but through it all, the sporting pilot would have a hard time finding something that better epitomized what speed freaks wanted, something more true to the core sporting values that the first GSX-R, the first real repli-racer of the modern era, embodied.

True, profiling fancyboys might have complained about uncomfortable ergonomics (the humble author raises his hand...), but when it came time to getting on with tearing it up at the racetrack, nobody gave a damn about low bars, high pegs, stiff suspension or peaky power.

But at this point in the evolution of our energetic and ever-changing two-wheeled universe, a profiling fancyboy has to ask. Why build this motorcycle? Why continue with a 750 in the face of a 600 and lOOOcc racing world? From Supersport to MotoGP, the perennial three-quarter-liter flagship, the bike that made American 75()cc Supersport racing into a Suzuki spec class, has precious few top-level competitive places to strut its stuff. Further, with the racing focus shifted to bigger and smaller machines, interest from the general public surely also has waned.

Or has it?

“We did expect sales of the R750 to decrease when we introduced the 1000,” said Masami Maga, one of many top brass on hand for Suzuki’s worldwide press introduction held near its Hamamatsu MQ. “But they dropped much less than we expected. And, of course, we need the bike to be successful to continue building it.”

Then he added in a wistful tone: “It is also the original GSX-R model.” What he was say ing is that it is a point of pride for Suzuki, for while die cruiser line languishes in a weird kind of neglect, and the company’s first 450cc four-stroke motocrosser is still a season away from being on sale, the GSX-R line flourishes, kicking ass on the road, on the track and on the sales floor. It remains true to its original concept of being a pure performance machine, using light materials and big horsepower in a compact, racer-replica inline-four-cylinder package. So, sure, current market trends and racing regulations have moved the 750cc sportbike from favor, but the core idea of balanced yet uncompromised performance remains as pure today as it was in 1985.

Actually, the original GSX-R750 debuted at the Cologne Motorcycle Show in the fall of 1984. The rest of the world got the bike in ’85, but release for our shores wasn’t scheduled until a year later. This just wouldn’t do, so Cycle World smuggled one into the States for a comparison test with the Yamaha FZ750 in June, 1985 (“The War of the 100-hp 750s”). From the story came this observation: “Suzuki’s concept for the GSX-R was simple: to be as close to a racebike as possible. Specifically, it should be a streetgoing replica of a 24-hour endurance racer...” That first GSX-R weighed 423 pounds without fuel, making it the lightest 750 on the market by more than 60 pounds! And it was lighter than the hottest 600s of the day, the Kawasaki Ninja and Yamaha FJ600. It had an aluminum frame at a time when most bikes were still being made from surplus sprinkler pipe, and a fullfairing that appeared as though it came right off a racebike.

And while that first model looks decidedly antique these days, with its narrow 18-inch wheels (using a 140mm-wide bias-ply rear tire!) and closely pitched cooling fins, it was at the time the most exotic-looking mass-produced sportbike ever made. Plus, the combination of the light chassis and high-power air/oilcooled engine whipped the wheelie-prone bike through the quarter-mile in 11.48 seconds at 118.26 mph, a terminal speed approaching that of Open-class sportbikes of the day.

Which is not all that unlike what today’s GSX-R750 does. While the 1996 model marked the return to core light-isright values (there was a porky stage when the bike flabbed up to 460 pounds dry), it was the 2000 model that really put the R750 back on the map. With 124 horsepower and a dry weight of 398 pounds on the CW certified scale, it combined power and handling in a way that only a 750cc machine could, taking Best Superbike honors in Ten Best balloting that year, and it handily won a comparison against its GSXR1000 and 600 stablemates (“Family Feud,” April, 2001).

Suzuki claims power is up and weight is down. Peak power is improved with a figure of 125.6 bhp at 12,750 rpm, although depending on which previous-generation testbike lined up against the ’04, the increase is either nominal, or meets the 5 percent reported by Suzuki. Our first 2000 GSXR750 made 124 bhp on the CW dyno, while one tested later that same year produced 119. As for weight reduction, our scales say the ’04 weighs 405 pound dry, compared with the 398 lbs. of the older model. At the dragstrip, performance matched that of the previous generation, with a 10.39-second/136.28-mph pass. Zero to 60 came in 2.8 seconds.

Even with no appreciable straight-line gain (it’s not like the old bike was a stone), the GSX-R750 is still a sweet combination of brutal-yet-manageable performance, especially in the face of monsters such as thel55-bhp/408-pound Kawasaki ZX-10R and Suzuki’s own King Kong GSXR1000 flagship.

Two days lapping Ryuyo, Suzuki’s aging test track near the company’s central Japan base, showed once again that there may be no better on-track tool. There are more than 3.7 miles in a lap of this high-speed circuit through the trees, with a back straight that measures more than a mile, which means you have enough time wide-open in sixth gear to think about the aerodynamic subtleties of your toes being in or out of the slipstream, to wonder what would happen if something let go in the engine, or if a tire failed. Or the fact that because you’re 6-foot-2 and 215 pounds, you punch one righteous hole in the atmosphere that lets your arch-joumo-rivals slingshot past you as you sit helplessly trying to crawl further under the paint and find a way to remove from your diet slices of pizza you already ate.

But the straights are only a small (okay looong) portion of the fun. Yes, it is very high speed-you basically hit the revlimiter in sixth gear twice per lap-but the big thrill comes because while tipping into the Tum 1 dogleg, the engine goes, brrrrrrr! on the rev-limiter as the smaller rolling circumference of the edge of the tire effectively shortens gearing! Then you get the, umm, relief of backshifting to fifth after that first dogleg in preparation for Turn 3. But the problem with 3 is that it’s actually a turn, which you are taking in the top of fifth with your knee on the deck. It is at moments like these that, while you always want to be aware of what danger lies where around a racetrack, it is of paramount importance to focus on the track, so as to not go off the track, if you get what I’m saying. It’s the kind of track that changes if not your life, at least your pants. All you can envision is a massive four-cylinder ball of flames, the bike grinding and cartwheeling across asphalt, then grass and full stop against a concrete wall with what look like used wrestling mats taped to them. This is not the place for savage over-riding of someone else’s motorcycle, for wild experiments in line or throttle application, just measured, sure, muscular and swift steering inputs, for no motorcycle is easy to steer at 165 mph.

“Ryuyo Proving Ground is not a racing circuit but a proving ground, ” read our orientation paperwork. “Racing circuits usually have enough escape zones for securing safety to avoid serious crashes; however, since this is a proving ground, you will see less escape zones as compared to ones on racing circuits. If you go out of the track, you may have serious injuries. ”

So the short and the short of it was that the runoff is, in fact, virtually nonexistent, especially at an average lap speed nearing 120 mph. Kevin Schwantz, on hand for the intro, related stories of testers who had met their ends at the track, reiterating quotes I found on his website prior to the trip about what a terrifying place Ryuyo was to test his vicious old RGV500 Grand Prix bike. He also related a storv about one of the testers who had died at the track, not by just hitting a wall but by flipping over one and drowning in a swamp. I’m shopping for a Joe Rocket floatation device now...

Not long after I had discovered the Schwantz web quotes, Suzuki PR man Mark Reese called to ask this: “The guys at the factory wanted me to make sure you had valid health insurance for the trip to Japan. Just a formality..And quite a confidence-inspiring one!

To be honest, once we were on the track and accustomed to the speeds, it wasn’t as bad as expected, and in fact all felt quite manly. At one point, as we sat waiting in the pit area to launch during a latter session, a light rain began to fall, dotting faceshields and fresh Suzuki blue paint with bubbles of Japanese water, which at press introductions usually spells some quality sitdown time in a cramped pitside tent. Not even the Italians let us out in the rain on a proper Grand Prix racing course.

But a Suzuki exec came over and waved us out onto the track, telling us to please be careful.

Over two days, there were no falls, no hard landings. In fact, virtually nothing happened. Two days of maximum acceleration and braking, wide-open throttle on the rev-limiter in every gear toward an indicated 180-plus mph. No brake fade, no missed shifts, no rise in engine temperature, not one thing amiss, just incredible performance, inspiring stability and amazing consistency.

It seemed remarkable that Suzuki would do this, have this press introduction at its test track, a place with these incredibly long straightaways and the same number of fifthand sixth-gear comers as second-gear ones, even as good as modem motorcycles have become.

But if you look back at the history of the GSX-R750, back at CWs world speed records set in 1985 aboard two stock GSX-Rs, piloted by Editorial Director Paul Dean, Editor-InChief David Edwards and Publisher Larry Little, among others, you realize that these motorcycles have always been made to run WFO. It was also a return to the track where the first GSX-R750 was introduced in 1985, where our own Steve Anderson attended the bike’s launch.

Because development money is no longer demanded by the 750cc class, while more and more is tunneled to 600s, the R750 has become the derivative model, contrary to how it’s been in the past for Suzuki. It’s a good way to go, though, with all the lightness and nearly 20 percent more power than the 600. Naturally, there are differences in the frame and swingarm on the bigger bike, for although these pieces share exterior dimensions, the castings are thicker in key places for more stiffness to cope with the extra power. Weight has nonetheless been chipped away from every component on the bike with precious, fine details like a tapered inner wall on the wristpins, thin little cookies of forged pistons that basically amount to ring-carriers, titanium valves, thinner wall thickness on the hollow camshafts, a light resin fuel-rail for the dualthrottle fuel-injection, “waisted” bolt shanks, narrow between the head and thread area, all details and knowledge culled from racing and somehow applied to a motorcycle that costs $9599 and comes with a 12-month unlimited-mileage warranty!

Anyway, you feel the lightness as you lift the bike from its sidestand, in every tum, in the way the engine revs and how quickly the GSX-R stops. Still, as I got more comfortable with the speeds and which way the turns went, the bike began to chatter during hard braking for the two second-gear corners. I asked the engineers for a little more preload, adding, “I weigh 215 pounds,” which is more than 50 percent of the bike’s weight.

There was much amused debate among engineers, R750 Project Leader Hiroshi lio among them, and seemingly some disbelief. They suggested only increased rebound damping, both in the fork and shock-no extra preload, surprisingly. Perhaps they thought it was futile. Nonetheless, the rhythmic cycling of the fork during braking for both of the two second-gear comers was reduced in magnitude, as was corner-entry drama. Stability also was improved in the very large-radius right-hander at the end of the 170-mph straight. This comer had pairs of bumps in succession through the tum, and with slightly tighter rebound, the chassis was more settled, which in turn settles the rider who has his knee on the pavement in the top of fourth gear, or bottom of fifth, depending on how much personal risk he is comfortable with in this turn.

Other than these small issues, at this super-fast Ryuyo test course, stability of the steering-damper-equipped GSX-R750 was never in question. In fact, it all seemed like harmless fun. Amazing.

The GSX-R has been a constant in the sportbike world, the quintessential distilled Superbike for the street from the very beginning. It is the very reason that we have the sportbikes we have today, lOOOcc machines that weigh close to 400 pounds and make 150 horsepower, 600s that weigh less and make 100-plus-bhp. The GSX-R was the fuel that fired the growth in the popularity of roadracing in America, because for the first time ever you could buy a bike that was, with a few small modifications, ready to win at the track, even if there are fewer and fewer classes in which it is eligible to compete. That’s why Suzuki continues to make this motorcycle and why people still buy it. Yes, the battles may have moved on, but the GSX-R750 is ready.

On the road or on the track, there still may be no better way to squash bugs.