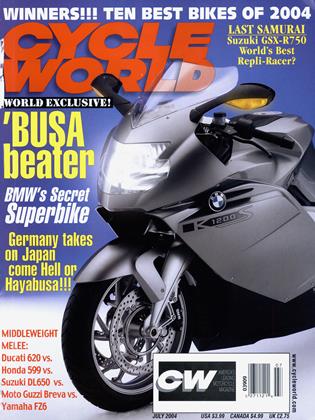

Kéjà Vu

A brief K-bike history

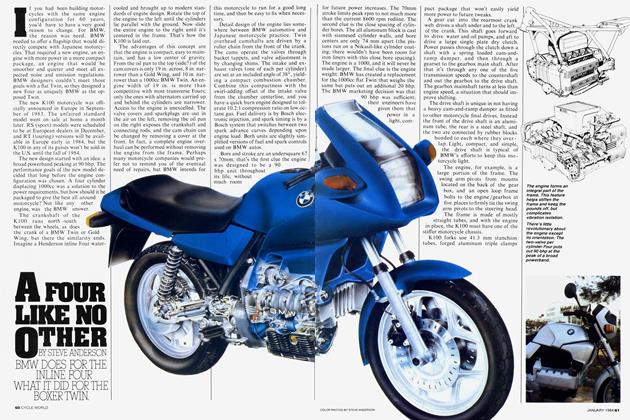

A little more than 20 years ago, I was having dinner in a pleasant outdoor café in Nice, France, with Stefan Pachernegg, the Austrian-born chief engineer for BMW motorcycles. Pachernegg, who passed away unexpectedly only a few years later, was one of the most forthright and outspoken chief engineers I’ve ever met-not the type to parrot the corporate line. When asked why the architecture of the then-new BMW K100 placed the gearbox behind the engine, instead of under it, he replied, “Maybe German engineers can’t think in three dimensions?”

He went on to explain that he had been hired after much of the definition of the new K-bike had been completed, and there were decisions that would have been handled differently if he had been there from the beginning. His job, he explained, was to either kill the project or see it to fruition.

Pachernegg may well have been the slender thread from which BMW Motorrad was dangling. There was a time when it was not at all certain that the company would continue with its motorcycle division. It may be hard for younger motorcyclists to believe, but by the end of the Seventies, it seemed that twin-cylinder motorcycles were doomed to be swept away by a tsunami of Japanese Fours. BMW’s motorcycle division was far from being a profit center, and the only things that kept the corporation from cutting its losses were heritage and image. Its German rival Daimler-Benz was the company that made cars and trucks, while BMW made sporty cars and sportier yet motorcycles. That distinction was worth preserving even at the cost of losses from the motorcycle division-as long as they didn’t get too out of control.

The old pushrod Boxer Twin was a large part of the problem. Its complex design, machining and assembly requirements kept production costs high. So when BMW decided to go with the first K-bike in 1985, it was an industrial design from the beginning-and actually cheaper to build (base engine to base engine) than the Twin. But management also insisted that the new Four would not enter BMW into the Japanese horsepower wars-this was the era of the six-cylinder Honda CBX and the first Suzuki GS1100, and European safetycrats were threatening to ban such insanely powerful machines. (If only they’d been exposed to today’s Kawasaki ZX-10R!)

BMW’s engineers complied with a design that surrendered before the first shot was fired: The first K100 acquired its displacement through a long 70mm stroke and a small 67mm bore, a combination that severely limited revs and power potential. That first K engine put out just 90 crank horsepower, and in later years it would prove a phenomenal challenge to squeeze more from an engine that was literally designed to have no room to grow.

Derivatives soon followed. The first was the 1986 K75, a three-cylinder slice off the original, a possible successor to the Boxer Twins, and as slow as the U.S. Postal Service. The counterbalanced Triple wasn’t as buzzy as the Four, however, and with a charismatic engine note proved relatively popular in the U.S. In its home market, though, German riders never seemed to get over the fact that it wasn’t any faster on the autobahn than a Japanese 500cc Twin.

On the four-cylinder front, more sport was eventually desired, and in 1989 BMW introduced the K1 with a four-valve head that finally brought output to the 100-horsepower level. The K1 combined an extreme riding position and flashy looks with lessthan-600cc performance, but its hardware would provide the basis for more powerful K-bikes in less extreme garb. Eventually, the original K engine would be bored and stroked to every last millimeter of possibility, and packaged in a chassis with vibration-shielding rubber mounts. The result, the 1997 K1200RS, was the longest sportbike extant, and heavy to boot, but proved a reasonably competitive sport-tourer when compared to Honda’a CBR1100XX-or at least the German magazines thought so.

Meanwhile, the introduction of the Kbike had made a lot of BMW fans think more fondly of Twins, and their desires became clear: No K-derived Triple or Four would satisfy them. That led in the early Nineties to the all-new, four-valve

R1100 Boxer, which along with the (originally Aprilia-built) F650 Single helped lead to a long and strong BMW sales revival. When it came time to think about doing a new K-bike, BMW’s motorcycle division was a different place than before, richer and more confident, and not willing to concede performance to the Japanese.

That’s what shows most strongly in this new K1200S, which is meant to go head-to-head with comparable Japanese sportbikes. So much for never entering the power wars!

And once again, derivatives will certainly follow. I, for one, can hardly wait for the imagined replacement for the K1200GT-a comfortable riding position for two, heated seat and grips, quality luggage and 160 horsepower without the flab of the current machine.

It’s a damn good thing Pachernegg thought the first K-bike worth finishing more than two decades ago.

Steve Anderson