Clipboard

MotoGP season setup

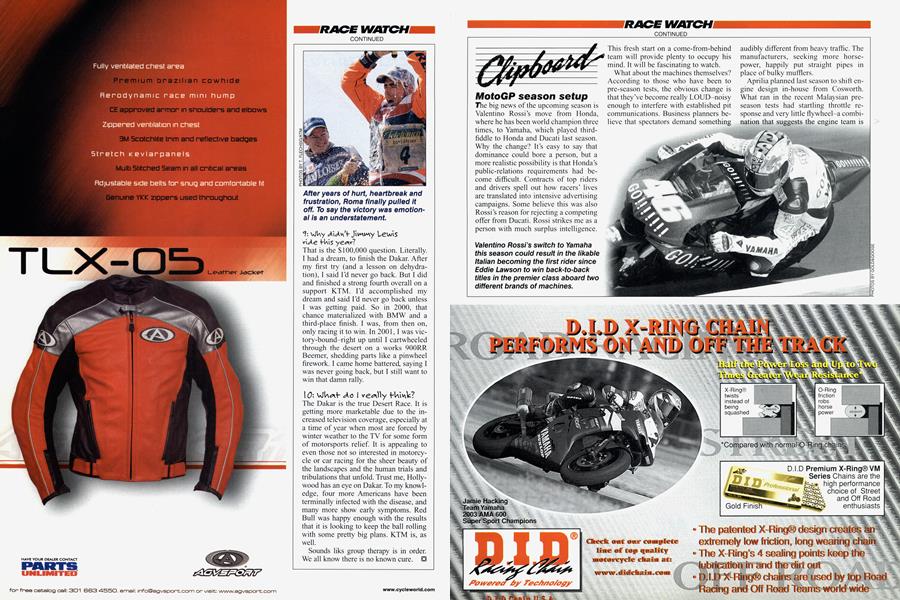

The big news of the upcoming season is Valentino Rossi’s move from Honda, where he has been world champion three times, to Yamaha, which played third-fiddle to Honda and Ducati last season. Why the change? It’s easy to say that dominance could bore a person, but a more realistic possibility is that Honda’s public-relations requirements had become difficult. Contracts of top riders and drivers spell out how racers’ lives are translated into intensive advertising campaigns. Some believe this was also Rossi’s reason for rejecting a competing offer from Ducati. Rossi strikes me as a person with much surplus intelligence.

This fresh start on a come-from-behind team will provide plenty to occupy his mind. It will be fascinating to watch.

What about the machines themselves? According to those who have been to pre-season tests, the obvious change is that they’ve become really LOUD-noisy enough to interfere with established pit communications. Business planners believe that spectators demand something audibly different from heavy traffic. The manufacturers, seeking more horsepower, happily put straight pipes in place of bulky mufflers.

Aprilia planned last season to shift engine design in-house from Cosworth. What ran in the recent Malaysian preseason tests had startling throttle response and very little flywheel-a combination that suggests the engine team is more concerned with power than with rideability at the moment. At the first Sepang test, the Aprilia showed a very high top speed-nearly 198 mph. At the second test, this was down 3-4 mph. This is a common Aprilia test profile: to run a high-horsepower engine first, then retune downward for a wider torque spread to find the quickest lap time.

Yamaha was so eager to have Rossi because it has been a long time since it had an accomplished development rider who can also win races. Carlos Checa is fast but falls often, and Marco Melandri is a recent arrival from 250s. With Rossi came his experienced core staff from Honda. If they mesh quickly with Yamaha, things can happen fast. Rossi’s bike at the second test had a new, duller engine sound, indicating an altered firing order. Anyone who has heard the current Suzuki or the 1982 Honda FWS has heard something similar-a flat, truck-like drone. The normal firing order for an inline-Four like Yamaha’s Ml is an outer cylinder firing first, then 180 degrees later one of the inner pair, then the other outer, followed by the remaining inner-all at even-fire 180 intervals. This is what generates the characteristic high shriek of a Four-a sound the Kawasaki ZX-RR still makes. An alternate firing scheme, retaining the normal “flat” crankshaft, might be to fire the outer pair together, then the inner pair 180 degrees later, repeating 540 degrees after that. This could be done to gain the notional traction advantage of narrow-firing-angle “big-bang,” which is believed to work by laying down a fresh tire footprint, unstressed by engine torque, and then applying four firing impulses to it in a short time. Such firing orders were employed on the 500cc two-strokes, but were later abandoned. A problem with narrow firing angle is that peak driveline torque is considerably increased, placing greater demands upon clutch and gearbox.

Suzuki is still struggling to become competitive in four-stroke MotoGR One theory of its failure thus far to do so claims that its advanced drive-by-wire system, integrating throttle, brakes, clutch and gearbox under a computerdriven system, needs more development time. Once the work is complete, so this theory goes, Suzukis will lead the pack into an all-electronic future that makes conventional, manually operated controls as outdated as the penny-farthing bicycle. Less sympathetic commentators suggest that the proper role for computer controls is as enhancements to proven, existing systems, and not as wholesale replacements for them. The bigger your gamble, the larger the potential loss. As Honda has so far been successful with what is basically a very powerful and fast conventional motorcycle, it may be that the path Suzuki engineers have chosen is premature. Former World Champion Kenny Roberts, Jr. seems to believe the Suzuki can improve for he is still with the team.

Because of the many separate skills involved in development, the work tends to fragment into separate specialties. The Öhlins or Showa technician deals with the suspension. The Michelin, Dunlop or Bridgestone engineers deal with tires. The computer and electronics technician handles the data. In all of this impressive division of labor, something could be overlooked-that the motorcycle must function as a whole, and can’t be “divided” in the same way. In the jargon of aerospace, at this point what’s needed is “systems integration.” That may be why the 40-year veteran race engineer Erv Kanemoto was in the Suzuki pit at both Sepang tests. And new engines are in the works.

Everyone expects Honda to raise the game this year. Why? Because the RC211V’s engine still contains old-tech features such as metal valve springs and turns “only” 16,500 rpm, there is plenty of room for performance growth. If a five-cylinder 990cc engine were given Formula One-like proportions and burned its mixture to state-of-the-art pressure, it could, rev to 20,000 rpm and make nearly 300 bhp. Honda is now said to be making about 240, so you can see that there are other horses in the barn, just waiting to be hitched up. Factory and satellite-team Honda riders were reaching maximum speeds of around 195 mph at Sepang with late-2003-spec engines, while recently retired (at least from racing) Tohru Ukawa on a new-spec machine ran 3 mph faster. Because aero horsepower scales as the cube of speed, this might require a 5 percent power gain, or another 12 bhp. On the other hand. Ukawa’s test bike may have also embodied aerodynamic refinements, in which case the power difference could be less.

Now what about Ducati? Last year, this small company surprised everyone by being Honda’s only effective challenger, winning one race and gaining many podiums in the hands of riders Loris Capirossi and Troy Bayliss. Sepang was something of a disappointment for them, as Bayliss was often seen to wait with evident impatience for his new GP4 machine to be made ready. There may also have been some engine or other failures. Yamaha and Rossi made the only times fully competitive with Honda’s at Sepang, but a week later in Phillip Island, Capirossi on the Ducati was fastest until Max Biaggi pipped him on the final day. These are pre-season tests, not races. Tests exist to test things, and not all tests succeed.

Americans can rejoice that Nicky Hayden had, by a hundredth of a second, the fastest lap time in the second Sepang test. What I found less pleasin’ is that Honda’s press release made a point o’ presentin’ him as a country hick. Hayden is an intelligent and experienced racer who deserves better than this. After a full season in Europe, he is acclimatized and ready to compete on an equal footing with the best. Hayden sensibly made his hot lap in the (relative) cool of the morning. Sepang is noted for its spirit-crushing humidity and 125-degree pavement temperatures.

Two-time World Superbike champ Colin Edwards has been consistently very fast in these pre-season tests-no surprise to anyone who saw any part of his inspiring 2002 WSB season. In that year he came from behind in a relentless, near-perfect drive to take the title. He was then fired by Honda-some say because he occasionally uses language saltier than “aw, shucks.” When Rossi left for Yamaha, Honda recalled Edwards from his sabbatical at Aprilia. There is no better, more dogged tactician.

Four-time 250cc title-winner Biaggi’s nemesis has been Rossi, who has been able to count on Max’s tires being worse than his own late in a race. Biaggi is fast and experienced, and wins races when he can escape the pressure. This is why

he is now on a Honda. Even one of the “second level,” it is currently the winning machine. He believes that given even nearly equal machines, he will be champion. Of course, that theory didn’t pan out last year.

Series veterans Sete Gibernau and Alex Barros are other strong Honda performers in these tests. They show that the rideability of these bikes erases the barrier that used to stand between former 250 riders and the top class.

Kenny Roberts Sr.’s Proton team fielded its first four-stroke engine design last year-a 60-degree V-Five. A second and

more refined design is expected this year, with a third iteration in the works. Roberts’ son Kurtis takes the seat vacated by Jeremy McWilliams’ move to Aprilia. This team’s program is to blend development and racing to achieve a quick, practical run-up from innocence to sophistication. The presence of F-1 engineer John Barnard on the team suggested to some that access to auto-racing mysteries would give a breakthrough advantage (they are based near Banbury, England, in the heart of the “F-l District”). Can motorcycle design leap forward, slipping the surly bonds of conventionality? If it can, that leap lies in the future. There is still time for the appearance of fearsome technological creation of slots, suction fans, wings, psychosomatic valves and geosynchronous orbital performance. Meanwhile, Kenny and his crew hew away at the purely practical problems of learning four-stroke racing as fast as they and their Malaysian Proton partners can contrive. The team’s obvious goal is to rise in the finishing order. I believe they will. Actual knowledge of racing is a more powerful tool than millions wasted on abstract factory policies.

These new MotoGP 990cc four-strokes are very little heavier than the 500cc two-strokes they have replaced. Think what that means in terms of engine structure. Down in the bottom-end is a crank with two, three or four crankpins, rotating 30-50 percent faster than the old two-stroke cranks did, while carrying counterweights sized for much bigger pistons. All this means large distorting forces applied to main-bearing saddles. If the minimum oil film thickness in those bearings is one micron (.00004-inch), how much distortion constitutes a disaster? Now think of the extra metal required to make cylinders up to 70 percent larger in diameter-and give them the stiffness to remain round enough for piston rings to seal despite distortion from head bolt forces, combustion pressure and piston inertia forces. And now figure out how to provide this increased stiffness with less metal than was used on the old twostrokes. Why less, if the weight is close? Because the two-strokes had no cams, tappets, valves, camboxes, cam drives, oil pumps, filters, or sumps. To hit the weight goals, design will have to teeter between marginal reliability and a raft of problems such as leakage, distortion and fatigue cracking.

Not only must the engine survive all of the above, but it must also deliver its power in a smooth, controllable way as part of an integrated package. The top MotoGP bikes are the fastest road racing machines ever built, but they remain recognizably motorcycles all the same-not explosive devices to be handled only by ultra-supermen. -Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontMending History

May 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Forgotten Passenger

May 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCInvisible Seal

May 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

May 2004 -

Roundup

RoundupDy-No-Mite! Benelli Unveils Tnt Naked Bike

May 2004 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupVtx Show-Shocker

May 2004 By Mark Hoyer