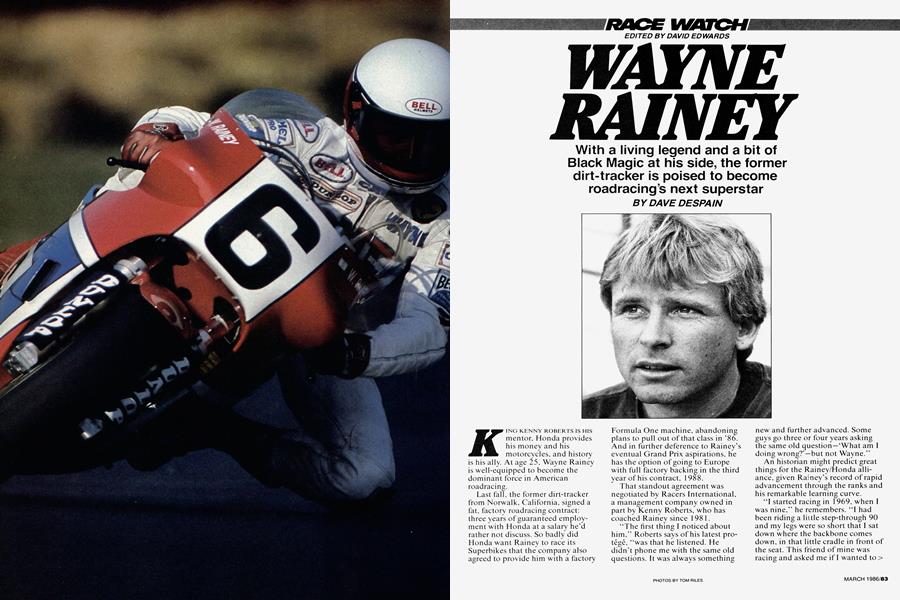

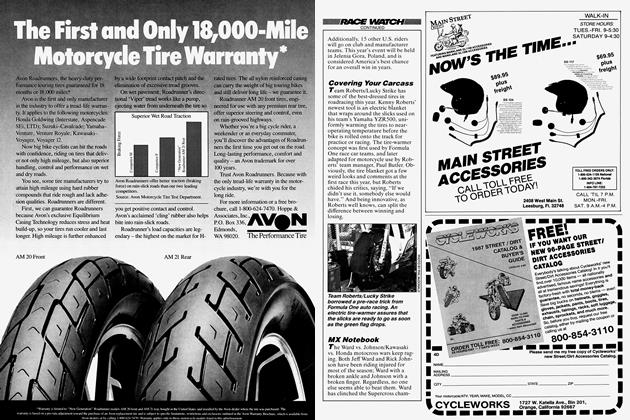

WAYNE RAINEY

RACE WATCH

With a living legend and a bit of Black Magic at his side, the former dirt-tracker is poised to become roadracing's next superstar

DAVID ED WARDS

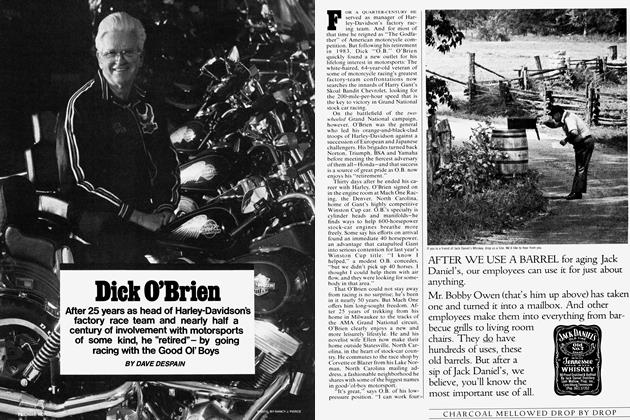

DAVE DESPAIN

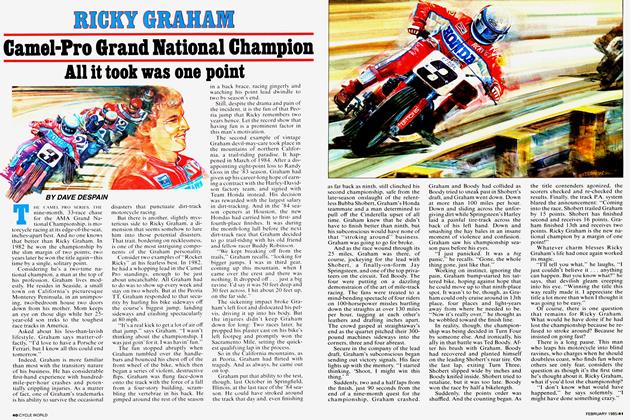

King KENNY ROBERTS IS HIS mentor, Honda provides his money and his motorcycles, and history is his ally. At age 25. Wayne Rainey is well-equipped to become the dominant force in American roadracing.

Last fall, the former dirt-tracker from Norwalk, California, signed a fat, factory roadracing contract: three years of guaranteed employment with Honda at a salary he'd rather not discuss. So badly did Honda want Rainev to race its

J

Superbikes that the company also agreed to provide him with a factory

Formula One machine, abandoning plans to pull out of that class in '86. And in further deference to Rainey’s eventual Grand Prix aspirations, he has the option of going to Europe with full factory backing in the third year of his contract, 1988.

That standout agreement was negotiated by Racers International, a management company owned in part by Kenny Roberts, who has coached Rainey since 1981.

“The first thing I noticed about him,” Roberts says of his latest protégé, “was that he listened. He didn't phone me with the same old questions. It was always something

new and further advanced. Some guys go three or four years asking the same old question—‘What am I doing wrong?’—but not Wayne.”

An historian might predict great things for the Rainey/Honda alliance, given Rainey’s record of rapid advancement through the ranks and his remarkable learning curve.

“I started racing in 1969, when I was nine,” he remembers. “I had been riding a little step-through 90 and my legs were so short that I sat down where the backbone comes down, in that little cradle in front of the seat. This friend of mine was racing and asked me if I wanted to > try it, so I went out and watched and thought, ‘Yeah, I'll try it.' Dad got one of those open-face helmets and put a football faceguard on it, and there I was. wetting my pants in the practice line.”

Success came quickly. And after eight years as a minibike and amateur hotshot, Rainey turned pro at 16. Riding Shell Thuett Yamahas, he cleaned up in the Novice and Junior dirt-track ranks, then struggled against the faster Harley-Davidsons as a rookie Expert in 1979. H-D-mounted for his sophomore season, he ranked 1 5th in the nation, but that 1980 campaign is better remembered for the phone call that changed his life.

“Kawasaki called Shell looking fora rider,” Rainey explains, “and he suggested me. They wanted somebody to ride their short-tracker in the National at Santa Fe Speedway. We went back and won the Expert trophy race and they were pretty happy, so they asked me if I'd like to ride some production roadraces.”

A quick “yes,” and Rainey was dispatched to the Keith Code Superbike School, where the principal was sufficiently impressed that he wrote a proposal to Kawasaki, offering to convert Rainey from a dirt-tracker to a pavement racer.

“I'd go to Keith's house every day and have my own little school. We’d go to Willow Springs, and he’d have five or six stopwatches and time me from corner to corner. I had to learn to use the front brake, because dirttrackers hardly ever do that. I was always bouncing the back wheel go-> ing into the corners and I wasn't smooth at all. Keith would sit me down and make me w rite down everything I was doing. That really helped me a lot.”

As precocious on pavement as he had earlier been on dirt. Rainey won 16 of l 8 West Coast production

roadraces in l 98 l. During that string, Kawasaki offered him the use of factory-team star Eddie Lawson's spare 250 for the Novice race at Loudon. New Hampshire; and that's when Rainey first made his Kenny Roberts connection.

Law son w as among the first cli-

ents signed by Roberts and his International Racers partner Gary Howard. Lawson recommended the deal to Rainey, who subsequently sought an audience with The King.

“Kenny called me on the phone two days before Loudon,” Rainey remembers, “and made me think about the different things he'd learned from Kei Carruthers and on his own. He just passed it on to me.”

“He was overshooting the corners,” Roberts recalls of that first conversation, “and not coming out fast enough. I told him for Loudon to keep that strategy, because that’s w hat it takes to go fast there; but after that. I told him he'd have to change and learn to come out of the corners faster.”

With Roberts’ coaching. Rainey won his first professional roadrace at Loudon, and Kawasaki responded with a factory Superbike contract for 1982. Just a year after his first amateur pavement event. Rainey was a factory roadracer.

Howard, who would later negotiate the lucrative Honda deal, demonstrated his bargaining-table> prowess early. He first convinced Kawasaki to let Rainey continue racing the dirt on a Harley, then got them to provide a truck to haul the bike! Instead, Rainey made an important decision to focus on roadracing.

“I thought there was more of a career there,” he says. “It was really hard to break away from the dirt tracks after l l years, but I could really see a future ahead of me. I was hearing about all the money the guys were making in Europe, I had the factory behind me, I was getting paid to race, flying around, hotels all paid for, so I knew it would be a lot better than driving around the States in my old, beat-up van.”

Once that decision was made, Rainey’s remarkable learning curve carried him to third behind Lawson and Mike Baldwin in the ’82 Superbike standings. In '83, he won six races and claimed the Superbike championship. And two days later, he was out of work.

“Gary Mathers, the team manager, called and told me Kawasaki had dropped out of roadracing for l 984,” recalls Rainey. “It was like a big empty hole in my heart. After being champion only two days, suddenly I didn't have a motorcycle to go out and race on as Superbike champion.”

Again, Roberts and Howard came to the rescue.

“Kenny wanted to kinda put me under his arm. so we went to Europe and put together a 250cc Grand Prix team for ’84,” explains Rainey. “I couldn’t believe what was going on. We'd get off the airplane and there would be cameramen and reporters. We’d walk down the street and people would be shouting, ‘The King!> The King!’ He was really a big deal over there.”

His pavement career reborn, Rainey won the '85 season-opening Formula Two race at Daytona, his second-ever ride on a 250. then launched his Grand Prix career in South Africa.

“On the way to the race. Kenny said. ‘You oughta do something over here to really make a name for yourself and get people talking about you.' In the first qualifying session it had just started to rain and I was the last guy out on the track. In five laps I passed everybody. I was coming up on World Champion Carlos Lavado and his teammate. Ivan Palazzese, but it was raining pretty hard in Turn One, so Carlos straightened up. I just went ahead and flicked ’er right in there and took out this poor Venezuelan Palazzese. I don’t know if I made a name for myself but I sure created a controversy.”

Rainey eventually set track records at six of the 12 GPs, but he ranked only eighth in the final standings because of one major problem: He couldn't master Grand Prix push-starts.

“The bike was really sensitive to heat,” he recalls. “If it was too hot or too cold, it wouldn’t start. I'd sit on the line watching the temperature gauge getting colder and colder, thinking, ‘Oh, no, it may not start.’ Everything’s dead-silent and then the light comes on, and once everybody got their bikes started. I couldn’t hear mine. I could always hear Roberts, though, on pit road as I came pushing by.”

Though Rainey figures that one season in Europe advanced his career by a couple of years, he chose not to return. “He didn't think the Yamaha would be competitive,” Roberts explains, “and for me to make a 250cc effort, I needed a reason. If he didn’t go back. I didn’t have a reason to go back.”

Rainey, eager to gain some 500cc experience, instead signed to race the 1985 season in America, with Bob McLean's privateer Honda team. The campaign was marred by injury and mechanical failure, but Rainey won two of the four 500cc races he contested and scored five 250cc victories in as many starts.

His affiliation with Roberts also provided him a temporary return to dirt-track racing: He was test pilot for the Mert Lawwill Harley that

Roberts rode last Labor Day at Springfield, Illinois. After a series of nickle-and-dime mechanical problems, Rainey closed the season with a brilliant run at Sacramento, California, losing the National to Scott Parker in a photo finish.

“I'm about two inches short of being satisfied with my dirt-track career,” he says of that race. “I really wanted to win a dirt-track National, but I think I’ve got dirttracking out of my system.”

With that, Rainey is set to launch a very serious assault on American roadracing. “I think if I do it right,” he forecasts, “I can win both titles— Superbike and Formula One. It’s not going to be easy, especially riding both classes, but I have enough experience now that each bike is going to help me on the other. I'm just going to take it race by race and make my game plan as I go.”

Roberts, who will field a 500cc Grand Prix team this year, can barely hide his disappointment that Rainey opted to stay in America. “He was my first choice for my team, and I would have matched what Honda paid him, though it would have only been for one year. The 500cc experience will be very good for him, but I don’t know about his rate of learning racing in America. Still, the kid’s gotta go where he wants to go.”

He wants eventually to go to Europe, but everybody would like to be over there. Everybody would like to be world champion. The dedication, the being away from home, the constant riding in bad conditions . . . that’s whàt separates world champions from wannabe’s.

“Right now,” says Roberts, “he’s got the drive and the determination. Whether he keeps it or not,” the three-time world champion concludes with a knowing laugh, “that’s Black Magic.”

His mentor’s view aside, Rainey is realistic about his decision. “I’ve run a grand total of four GP races on a 500. Am I ready to get over there and mix it up with Freddie Spencer and Eddie Lawson?”

Two stateside seasons with Honda will overcome that lack of experience, and Roberts will remain squarely in his corner. If the Black Magic holds until 1988, Wayne Rainey will then be ready for the final step in his remarkable career: the world championship. S

View Full Issue

View Full Issue