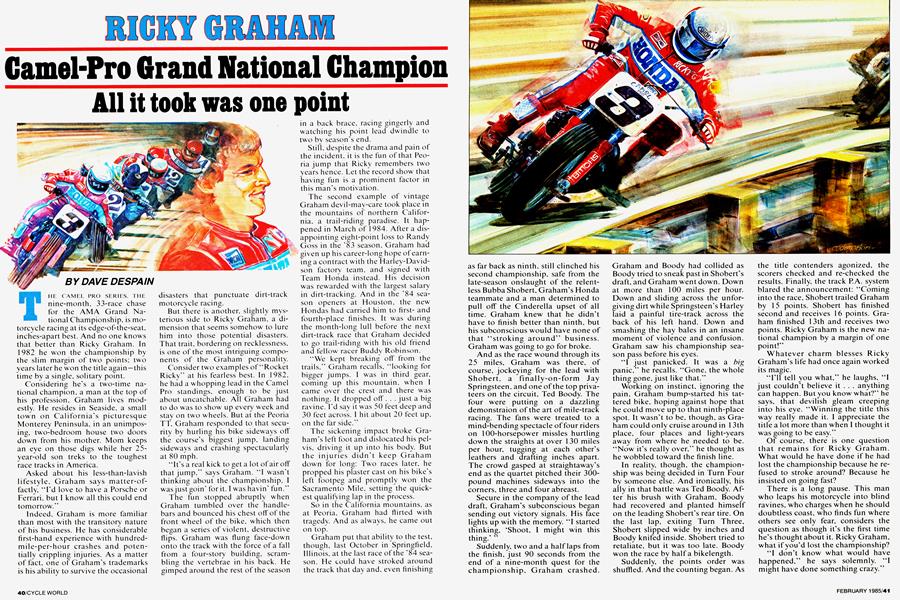

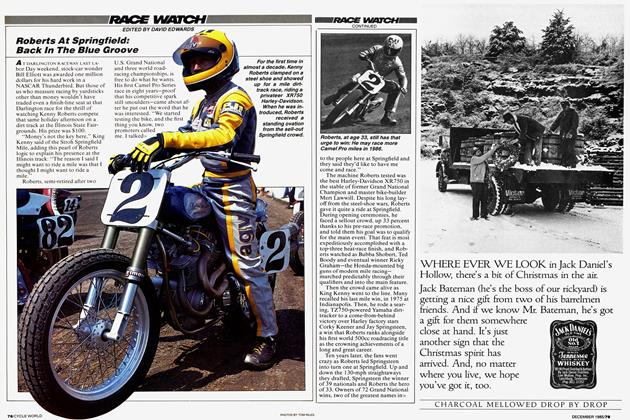

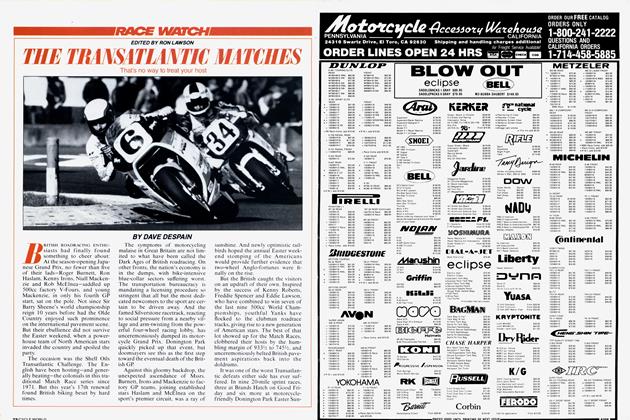

RICKY GRAHAM

Camel-Pro Grand National Champion

All it took was one point

DAVE DESPAIN

THE CAMEL PRO SERIES. THE nine-month, 33-race chase for the AMA Grand National Championship. is motorcycle racing at its edge-of-the-seat. inches-apart best. And no one knows that better than Ricky Graham. In 1982 he won the championship by the slim margin of two points; two years later he won the title again-this time by a single, solitary point.

Con~sidering he's a `two-time na tional champion. a man at the top of his profession. Graham lives mod estly. He resides in Seaside, a small town on California's picturesque Monterey Peninsula, in an unimpos ing. two-bedroom house two doors down from his mother. Mom keeps an eye on those digs while her 25year-old son treks to the toughest race tracks in America.

Asked about his less-than-lavish lifestyle. Graham says matter-of factly. "I'd love to have a Porsche or Ferrari, but I know all this could end tomorrow."

Indeed. Graham is more familiar than most with the transitory nature of his business. He has considerable first-hand experience with hundred mile-per-hour crashes and poten tially crippling injuries. As a matter of fact, one of Graham's trademarks is his ability to survive the occasional disasters that PU nctUate dirt-track motorcycle racing.

But there is another, slightly mys terious side to Ricky Graham. a di mension that seems somehow to lure him into those potential disasters. That trait, bordering on recklessness. is one of the most intriguing compo nents of the Graham personality.

Consider two examples of "Rocket Ricky" at his fearless best. In 1 982, he had a whopping lead in the Camel Pro standings. enough to be just about uncatchable. All Graham had to do was to show up every week and stay on two wheels. But at the Peoria TT, Graham responded to that secu rity by hurling his bike sideways off the course's biggest jump. landing sideways and crashing spectacularly at 80 moh.

"It's a real kick to get a lot of air off that jump." says Graham. "I wasn't thinking about the championship. I was just goin' for it. I was havin' fun."

The fun stopped abruptly when Graham tumbled over the handle bars and bounced his chest off of the front wheel of the bike, which then began a series of violent, destructive flips. Graham was flung face-down onto the track with the force of a fall from a four-story building. scram bling the vertebrae in his back. He gimped around the rest of the season in a back brace, racing gingerly and watching his point lead dwindle to two by season's end.

Still, despite the drama and pain of the incident, it is the fun of that Peo ria jump that Ricky remembers two years hence. Let the record show that having fun is a prominent factor in this man's motivation.

The second example of vintage Graham devil-may-care took place in the mountains of northern Califor nia, a trail-riding paradise. It hap pened in March of 1984. After a dis appointing eight-point loss to Randy Goss in the `83 season. Graham had given up his career-long hope of earn ing a contract with the Harley-David son factory team, and signed with Team Honda instead. His decision was rewarded with the largest salary in dirt-tracking. And in the `84 sea son openers at Houston, the new Hondas had carried him to firstand fourth-place finishes. It was during the month-long lull before the next dirt-track race that Graham decided to go trail-riding with his old friend and fellow racer Ruddy Robinson.

"We kept breaking off from the trails." Graham recalls. "looking for bigger jumps. I was in third gear. coming up this mountain, when I came over the crest and there was nothing. It dropped off. . . just a big ravine. I'd say it was 50 feet deep and 30 feet across. I hit about 20 feet up. on the far side."

The sickening impact broke Gra ham's left foot and dislocated his pel vis, driving it up into his body. But the injuries didn't keep Graham down for long: Two races later, he propped his plaster cast on his bike's left footpeg and promptly won the Sacramento Mile. setting the quick est qualifying lap in the process.

So in the California mountains, as at Peoria, Graham had flirted with tragedy. And as always, he came out on top.

Graham put that ability to the test. though. last October in Springfield, Illinois, at the last race of the `84 sea son. He could have stroked around the track that day and, even finishing as far back as ninth, still clinched his second championship, safe from the late-season onslaught of the relent less Bubba Shobert, Graham's Honda teammate and a man determined to pull off the Cinderella upset of all time. Graham knew that he didn't have to finish better than ninth, but his subconscious would have none of that "stroking around" business. Graham was going to go for broke.

And as the"raciwo~ind through its 25 miles, Graham was there, of course, jockeying for the lead with Shobert, a finally-on-form Jay Springsteen, and one of the top priva teers on the circuit, Ted Boody. The four were putting on a dazzling demonstraion of the art of mile-track racing. The fans were treated to a mind-bending spectacle of four riders on 100-horsepower missles hurtling down the straights at over 130 miles per hour, tugging at each other's leathers and drafting inches apart. The crowd gasped at straightaway's end as the quartet pitched their 300pound machines sideways into the corners, three and four abreast.

Secure in the company of the lead draft, Graham's subconscious began sending out victory signals. His face lights up with the memory. "I started thinking, `Shoot, I might win this thing.'"

Suddenly, two and a half laps from the finish, just 90 seconds from the end of a nine-month quest for the championship, Graham crashed. Graham and Boody had collided as Boody tried to sneak past in Shobert's draft, and Graham went down. Down at more than 100 miles per hour. Down and sliding across the unfor giving dirt while Springsteen's Harley laid a painful tire-track across the back of his left hand. Down and smashing the hay bales in an insane moment of violence and confusion. Graham saw his championship sea son pass before his eyes.

"( just panicked. It was a big panic," he recalls. "Gone, the whole thing gone, just like that."

Working on instinct, ignoring the pain. Graham bump-started his tat tered bike, hoping against hope that he could move up to that ninth-place spot. It wasn't to be, though, as Gra ham could only cruise around in 1 3th place, four places and light-years away from where he needed to be. "Now it's really over," he thought as he wobbled toward the finish line.

In reality, though, the champion ship was being decided in Turn Four by someone else. And ironically, his ally in that battle was Ted Boody. Af ter his brush with Graham, Boody had recovered and planted himself on the leading Shobert's rear tire. On the last lap, exiting Turn Three, Shobert slipped wide by inches and Boody knifed inside. Shobert tried to retaliate, but it was too late. Boody won the race by haifa bikelength.

Suddenly. the points orde~r was shuffled. And the counting began. As the title contenders agonized, the scorers checked and re-checked the results. Finally, the track PA. system blared the announcement: "Coming into the race. Shobert trailed Graham by 15 points. Shobert has finished second and receives 16 points. Gra ham finished 13th and receives two points. Ricky Graham is the new na tional champion by a margin of one point!"

Whatever charm blesses Ricky Graham's life had once again worked its magic.

"I'lrtell you what," he laughs, "I just couldn't believe it . . . anything can happen. But you know what?" he says, that devilish gleam creeping into his eye. "Winning the title this way really made it. I appreciate the title a lot more than when I thought it was going to be easy."

Of course, there~ is one question that remains for Ricky Graham. What would he have done if he had lost the championship because he re fused to stroke around? Because he insisted on going fast?

There is'~t 1o'~ig pause. This man who leaps his motorcycle into blind ravines, who charges when he should doubtless coast, who finds fun where others see only fear, considers the question as though it's the first time he's thought about it. Ricky Graham, what if you'd lost the championship?

"I d~n't know what wculd have happened," he says solemnly. "1 might have done something crazy."

View Full Issue

View Full Issue