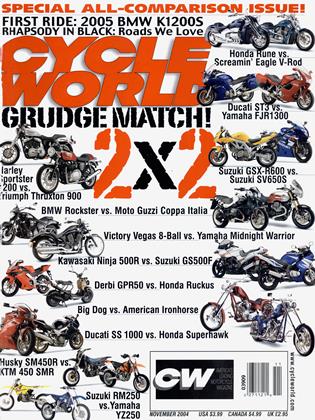

V-RODS IN DRAG

RACE WATCH

The Vance & Hines Harley went from 0 to dominance in 2 years...and then the NHRA stepped in

BRUCE FISCHER

IT ONLY LASTS ABOUT SEVEN SECONDS, but what a seven seconds it is! With motors screaming wide-open and rpm bouncing off rev-limiters, the light goes green and WHAM! a pair of motorcycles explodes down the quarter-mile in a breathtaking display of sound and fury—and, of course, acceleration. It’s NHRA Pro Stock Bike drag racing, pitting the fastest two-wheelers of their kind against one another to determine the same outcome that hot-rodders have been contesting for close to a century: Who can get to the end of the quarter-

mile first? It’s gearhead entertainment at its best.

But like the tip of an iceberg, that’s just the part that you see; what you don’t see is all the hard work that goes on behind the scenes. Each bike might make only a handful of runs during a weekend’s eliminations, but the time between those runs is spent inspecting, adjusting, replenishing, recalibrating and, on occasion, repairing, all in the hope of knocking a few thousandths off the next run’s E.T.

To get an up-close-and-personal view of what’s involved in keeping a frontrunning Pro Stock Bike competitive during a typical race meet, we spent an entire weekend with Harley-Davidson’s Screamin’ Eagle/Vance & Hines team during the Mile High Nationals at Bandimere Speedway in Denver this past July.

It was an eye-opening experience.

The V&H team is the only one in NHRA competition that fields two bikes, a pair of Pro Stock V-Rods ridden by young star G.T. Tonglet and Andrew Hines, son of legendary tuner and team leader Byron Hines. The bikes are attended to by Andrew’s brother Matt, himself a three-time NHRA Pro Stock champion as a rider, plus long-time associate Joe Vanderbrink, mechanic Greg Cope, all-around helper Meredith Schultz and truck driver Ray Veirs. With the team’s two large motorhomes and giant 18-wheeler that hauls the equipment, just getting to the events is a job in itself. The team’s other namesake, motorcycle drag-racing legend Terry Vance, also is on hand at most events.

We arrived at the track on Thursday and found that the pace of activities was fairly relaxed. That’s the day usually devoted to setting up pit areas and running the bikes through initial tech inspection. Aside from those routine chores, not much happens until Friday.

Except that at noon on this particular Friday, the heavens opened and dumped non-stop rains on the entire Denver area well into the night, erasing all of the day’s qualifying sessions. Forus, however, the upside of this interruption was that it gave us ample time to explore the impact of a controversial rules change that had been imposed on the Pro Stock Bike class just weeks earlier.

After more than two years of development, disappointment and second-guessing by trackside pundits, the Screamin’ Eagle V-Rods had finally begun to enjoy the kind of success everyone expected from a team run by the illustrious Vance & Hines organization. Consistently fast qualifying times, a few track records, three final-round wins and a commanding points lead by Andrew Hines had quieted the skeptics. But after Hines’s record-setting 7.010-second run en route to a win at Englishtown, New Jersey, everyone knew that a rules adjustment was inevitable. For quite some time, the NHRA had allowed two-valve pushrod V-Twins a distinct displacement and weight advantage. Twins could weigh as little as 575 pounds (bike and rider), and those with a 60-degree Vee spread, such as the V-Rod, were allowed 160 cubic inches, while the traditional 45-degree motors could be as big as 200 cubes. Four-cylinder bikes, meanwhile, have a 600-pound weight minimum and cannot exceed 92 cubic inches. The intention of this disparity was to attract the big boomers into what had been mostly a four-cylinder field dominated by Suzukis.

But that all changed a mere two days before the June event at Gateway International Raceway in Madison, Illinois. To the shock and dismay of the V&H team, the NHRA didn’t just level the weight rule by mandating a 600-pound minimum for all Pro Stock bikes, it added yet another 15 pounds for those with 60-degree motors, which had proven to be better performers than the 45-degree Vees. That meant the V-Rods would have to weigh in 15 pounds heavier than anything else running in the class.

This left the V&H team with no chance to make any adjustments prior to the Gateway event besides arbitrarily bolting on some chunks of lead, with no time for any testing to assess the results. So, the V-Rods only managed to qualify 14th and 15th at Gateway, posting E.T.s that, on average, were .2-second slower than usual. And by Sunday’s second round, both bikes had been eliminated. Matt Hines claims that it takes about 18 horsepower to regain ,2-second of elapsed time, and weight placement always is critical to a Pro Stocker’s hook-up ability; obviously, a lot of midnight oil had to be burned in the two weeks before the Denver shootout.

Some of the other racers in this class, including reigning champ Geno Scali, would rather have seen an increase in displacement for the Fours (maybe up to 100 cubes), or the allowance for them to use fuel-injection like the NHRA has let the Harleys run for the past three years. “It’s racing. Why slow anyone down?” said Scali.

Other “American”-powered teams, who already were struggling to make shows, found the change to be very severe. The new S&S-powered “G Squared” Buell of George Bryce and George Smith didn’t run at Denver, and the team reported it wouldn’t return until it could make the bike competitive again. Considering that just two years ago, none of the pushrod motors could even make the show, Matt Hines opined that, “Maybe the NHRA’s decision wasn’t well-thought-out.” And if the comments offered by many fans during the weekend are any indication, most of them also disagree with the NHRA’s decision.

By Saturday, the meteorological storm front at least had moved out and weather conditions were excellent for the two remaining opportunities everyone had to make the field. The three-week break since the Gateway race had given the V&H team time to cope with the new weight regulations. They machined oil pans from solid billet steel that put 18 pounds of added mass down low and forward where it is the least detrimental to the bike’s all-important launch char-

acteristics. They also filled the hollow frame crosstubes at the bottom of the chassis with lead to bring the bikes up to the minimum weight. Byron Hines acknowledged that he had given the engine a few tuning tweaks but, in typical race-tuner style, was unwilling to talk about them. There was still a big question mark about how well the engines would function, especially in Denver’s high-altitude atmosphere; they don’t call it the “Mile High Nationals” for nothing. But, having done all the initial dyno work in nearby Trinidad, Colorado, the elder Hines knew his motor could make reasonable power at high elevations.

That’s always a concern for everyone when racing at Denver. “The bikes don’t run the quick numbers in the high altitude, so it puts a lot on the drivers to cut good lights,” said Scali. “You’ll see a lot of matchups won on the starting line this weekend.” At the time, Scali wasn’t aware that his remarks would turn out to be quite prophetic.

Early on Saturday, Tonglet said he would be happy with a mid-pack time, but that comment was disregarded after he posted a 7.560 E.T., quickest in the first session, with Hines a solid third at 7.590. This was much better than anyone expected. When the bikes returned to the pits, the numbers from the onboard data acquisition systems were downloaded to the computer in the trailer and closely scrutinized. After analysis of that information and some discussion, a final-drive ratio change was ordered. In what seems like no time at all, sprockets were swapped, clutch packs inspected and all the other prep work completed.

Although both riders often help with the wrench-spinning, another important facet of their job is to “meet and greet” the hordes of fans who gather outside the roped-off pit area. So, after finishing their mechanical tinkering, they handed out free posters, signed endless autographs, shook countless hands.

The crew finished their work in time for Saturday’s final qualifying session, during which Hines stunned the crowd by rewriting both ends of the track record with a 7.509 blast at more than 185 mph. Tonglet was no slouch, either, posting a 7.550 run at over 176 mph, good for third in the standings. This meant that the two V-Rods couldn’t possibly race each other until the last round of eliminations, an outcome that prompted lots of handshakes and smiles between team members. The bikes then received their requisite servicing before all the gear was stowed for the night. Apparently, all that hard work during the previous weeks was bearing fruit.

Sunday dawned bright and clear, bringing the warmest temperatures of the weekend. It was time for the money rounds and those all-important championship points. Before the driver/rider introductions and other pre-final hoopla, the equipment was set up one more time and numerous small adjustments were made to the V-Rods to accommodate the warmer weather.

In the first round, Hines defeated Redell Harris with a 7.530, the second-best time, while Tonglet advanced over Fred Camarena with a 7.640 posting. The bikes were hurried back to the pits where, after a short flurry of smiles and high fives, the crew went into action. The same amount of work that was done almost leisurely between time trials on Saturday now had to be completed before the next round of racing in less than 75 minutes. With things seemingly headed in the right direction, the focused crew performed another gear change, made slight timing and fuel-tuning adjustments and completed a routine clutch service. All this while Andrew and Tonglet, of course, engaged in more rider-fan interaction. Next thing we knew, it was time to get back up to staging for another attempt to advance toward the final round.

Oops! Tonglet left too soon against Shawn Gann, turning on one of 11 redlights that plagued the field during eliminations. Hines ran a solid 7.600 that put Scali on the trailer and advanced the VRod into the semifinal go. Back in the work area, scowls and smiles abounded as one bike was done but the other still had a chance at the big win. The time passed fast, but now, with twice as many hands to do the work, the crew efficiently got the remaining machine fully prepped.

Tonglet was beside himself for lighting the red bulb but he put on a smile, responded to the sympathetic crowd and inked his John Hancock on yet more posters.

As the Hines-piloted mount returned to the staging area, expectations were high, since a win would put him into the finals. The two bikes rolled into the staging beams, the tree went yellow and-damn!-the dreaded crimson glowed again on the VRod side of the strip. To add insult to injury, Hines’s opponent, Craig Treble, had his engine explode in a ball of flame before hitting the stripe, slowing him enough have been easily outrun.

Back in the V&H pit, that unmistakable look of utter disappointment was on everyone’s face. They all knew that they weren’t beaten, but they also knew that they did lose.

Even so, the drama wasn’t over yet: Treble had to face Gann in the final, but had a greatly wounded motorcycle. Matt Hines (who used to own the bike that Treble campaigns) and brother Andrew, along with Tonglet, Vanderbrink and Cope, all joined a host of people from other defeated teams who rushed to Treble’s trailer to help him change engines before the last race. Wrenches spun. Parts were strewn about. Bodies charged to other trailers for last-minute bits. Finally, to a congratulatory burst of applause from onlookers, the bike fired just in time to make it back to the starting line.

As it turned out, Treble lost to Gann. But much satisfaction was derived anyway from the camaraderie and sportsmanship exhibited by everyone who helped Treble get to the line in time.

After the sound and the fury were over, cold brews appeared while everything was packed up amid a laid-back atmosphere. With its respectable showing in Denver, the team hoped to resume its earlier string of successes at the next challenge in Sonoma, California, where the almost-sea-level altitude is a horsepower equalizer. More brainstorming, more fiddling and more hard work will likely result in more wins. Maybe it will even put the much-coveted Pro Stock Bike championship trophy on display in that big brick building on Juneau Avenue in Milwaukee.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

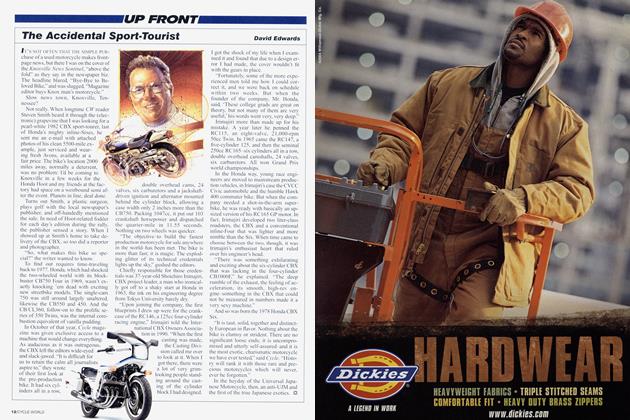

Up FrontThe Accidental Sport-Tourist

November 2004 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsKtm Unplugged

November 2004 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBigger Big Bangs?

November 2004 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2004 -

Roundup

Roundup2005 Bmw K1200s: Too Fast For the Autobahn?

November 2004 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupBmw Goes To Motogp

November 2004 By Bruno Deprato