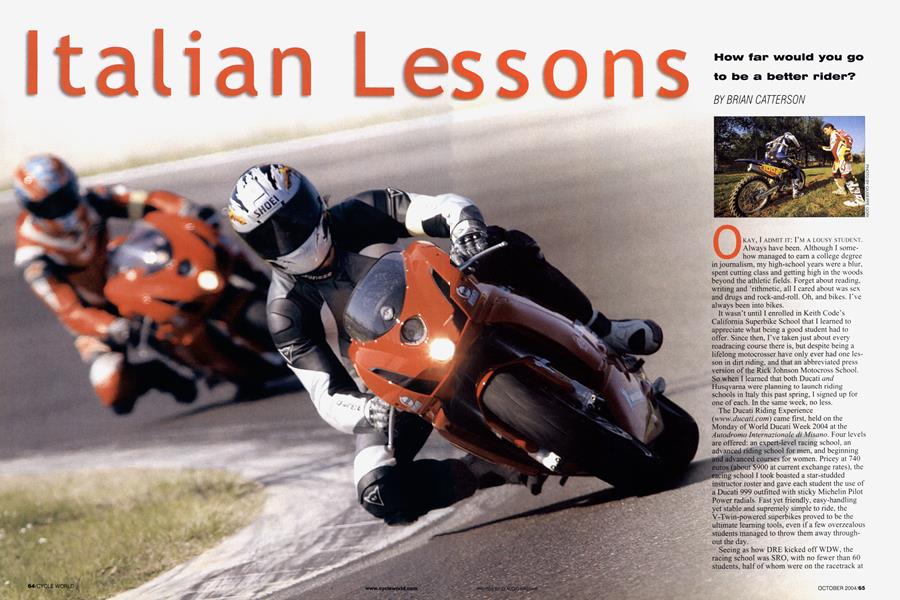

Italian Le ssons

How far would you go to be a better rider?

BRIAN CATTERSON

OKAY, I ADMIT IT: I'M A LOUSY STUDENT. Always have been. Although I somehow managed to earn a college degree in journalism, my high-school years were a blur, spent cutting class and getting high in the woods beyond the athletic fields. Forget about reading, writing and 'rithmetic, all I cared about was sex and drugs and rock-and-roll. Oh, and bikes. I've always been into bikes.

It wasn’t until I enrolled in Keith Code's California Superbike School that I learned to appreciate what being a good student had to offer. Since then, I’ve taken just about every roadracing course there is, but despite being a lifelong motocrosser have only ever had one lesson in dirt riding, and that an abbreviated press version of the Rick Johnson Motocross School. So when I learned that both Ducati and Husqvama were planning to launch riding schools in Italy this past spring, I signed up for one of each. In the same week, no less.

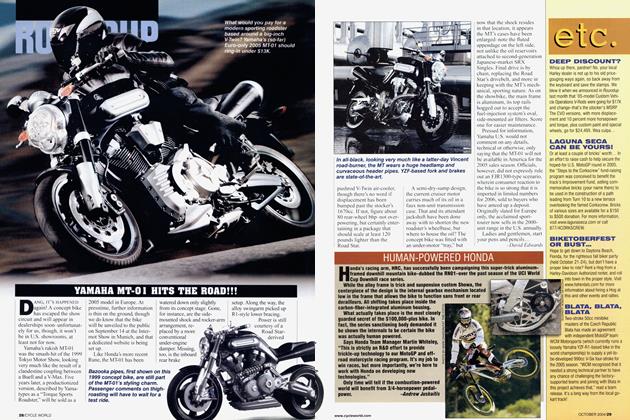

The Ducati Riding Experience (www.ducati.com) came first, held on the Monday of World Ducati Week 2004 at the Autódromo Internazionale di Misano. Four levels are offered: an expert-level racing school, an advanced riding school for men, and beginning and advanced courses for women. Pricey at 740 euros (about $900 at current exchange rates), the racing school I took boasted a star-studded instructor roster and gave each student the use of a Ducati 999 outfitted with sticky Michelin Pilot Power radiais. Fast yet friendly, easy-handling yet stable and supremely simple to ride, the V-Twin-powered superbikes proved to be the ultimate learning tools, even if a few overzealous students managed to throw them away throughout the day.

Seeing as how DRE kicked off WDW, the racing school was SRO, with no fewer than 60 students, half of whom were on the racetrack at any one time, split into small groups of six so there was plenty of one-on-one instruction. The instructor for my group was no less than Marco "Lucky" Lucchinelli, the charismatic 1981 500cc world champion on a Suzuki RG500 who helped Ducati develop the original eight-valve 851 before going on to manage

the factory Superbike team. Joining me were five other English-speaking students, including photographer Jim Gianatsis of www.fastdates.com fame, plus three other Americans and one Swede.

Teaching in a foreign language initially worried Marco, as he warned, I speak only paddock English. Everything I know, I learned from talking to Barry Sheene and Kenny Roberts." With those two characters as teachers, suffice it to say he has a colorful grasp of the language! But we managed to communicate just fine.

Headmaster or head World Champion Ma, reputation for being himself long enough instructor at the Duc~ T he program consisted of six 30-minute sessions, the first two of which were spent following Marco in formation to learn the 2.5-mile track. Fortunately, I'd been to Misano before for WDW 2000 and various press intros, so didn't need many laps to get up to speed. Derided by some Grand Prix and Superbike racers as unsafe, Misano is nonetheless a fabulous race circuit, flat but with a wide variety of corners, most exciting of which is the succession of four left-handers that lead onto the 150-mph back straight. The fact that Wayne Rainey had his career-ending crash ly has tainted some riders' opinions, but the circuit wasn't at fault; if it were in the U.S. it would be the safest track in the land. Not to mention the best-or maybe the second-best behind Laguna Seca. at Misano undoubted-

The remaining sessions saw us each follow Marco for a few laps, after which he followed us for a few, then cut us loose to lap on our own. Between sessions we sipped espres so, nibbled on pastries, posed for caricatures by renowned cartoonist Matitaccia (Italian for "Pencil," whose real name is Giorgio Serra) and listened to Lucchinelli's advice in the lavishly appointed garage. -

Surprisingly, the only observation Marco made about my riding was, "You don't use the rear brake." "I've tried, but my boot gets in the way in right-handers," I said in defense. "You should use it," he said. "Why?" I asked. "Because there are two," he replied. Uh, yeah.

Marco hammered home his point by asking if the rear brake was useless, why did Mick Doohan go to the trouble

of having a thumb lever fitted after his serious leg injury? Using the rear brake helps settle the bike entering corners, he explained, and allows you to scrub off speed mid-corner where applying the front brake could result in a low-side. The theoretical higher cornering speed this allows also helps save the rear tire, because you don't have to accelerate as hard at the exit.

Duly noted, and so whenever Marco followed me after that, I made a point of trailing the rear brake so deep into corners that he'd know it couldn't pos sibly be the front brake mak ing the light come on. But I didn't feel any faster, and my boot still got in the way in right-handers.

An incident in which using the rear brake helped not one iota occurred shortly thereafter, when my Swedish classmate, Paul Guldstrand, high-sided in front of me exiting the final chicane before the start/finish straight. I was setting up to draft past him at the time, thus was close behind, and with his bike spinning to the left, him tumbling to the right and the pit wall fast approaching, I literally had nowhere to go. And so with God and a dozen onlookers as my witnesses, I braked as hard as I could (with both brakes-honest, Marco!) and rode the longest stoppie of my life before coming to a halt literally between Paul’s thighs! The only problem was my bike was still nearly vertical, so if I let go of the brake lever, the front wheel would have, uh, ruined his day. Realizing this, I took a giant step to the left, performing a graceful shoulder roll, and the bike tipped over onto its side so gently that the only damage was a slightly bent shifter lever, promptly straightened back in the pits. Paul was bruised and battered but not seriously hurt, and later thanked me, said his unborn children thanked me and promised to buy me a beer, which I only now realized he never did. Ingrate.

case? Former 500cc Lucchinelli has a bit crazy, but behaved serve as a guest Riding Experience.

N ow, I may not be your typical student (I'm actually an instructor at Club Desmo track days), but I have to admit I was somewhat disappointed by the DRE curriculum. The only formal instruction came after a typi cally sumptuous Italian lunch in the paddock restaurant, when we re-convened in the press room to watch an ani mated video of a rider going through various corners. It was only after speaking to Ducati Corse boss Claudio Domenicali that I learned the video was produced using the latest data acquisition, not just on the bike but in the rider's leathers as well. As impressive as was the technol ogy behind the images, however, the message was nothing new: It merely suggested that you brake as hard as possible while straight up and down, go in deep, trail off the brakes, turn quickly and then get back on the throttle, clipping a late apex before driving onto the following straightaway.

I'm also sorry to say that Marco didn't sho~v me much on the racetrack. The 49-year-old today runs a company called CMJ, which makes vintage-style leather jackets like the ones sold by Ducati Performance, but he also

recently spent time in prison on drug charges. No surprise, then, that he was out of practice on a bike, and had a hard time keep ing up with the faster students. At the end of one session, he chas tised me in the pits, saying, "You only care about going fast. You should do the lessons slow and then they'll help you when you go fast." The thing is, I wasn't going that fast! But while Marco's on-track tutelage may have been lack-

ing, he made up for it in the pits, dutifully answering each of our questions and showing the sort of insight that only a rider/team manager with his experience can pos sess. He talked about the importance of being smooth, of turning the bike with pressure from your inside hand and foot, but countering those inputs with the opposite hand and foot so that the bike doesn't just "flop" over. He told us of the importance of standing on the footpegs while making transitions, getting your butt off the seat by just a few millimeters so that it doesn't drag across and upset the chassis. And he discussed the finer points of braking, of how you should squeeze the front brake lever soft ini tially to compress the fork and then add pressure once the front tire got a good bite. I can't honestly say that I learned anything new, but I had some of my beliefs reaf firmed, and my less-experienced classmates said they learned a lot, so it was a worthwhile experience. And this was the first school; the curriculum will likely improve with time.

I nevitably. talk turned to racing. and Marco regaled us with tales from his competitive years. He reminded us that Valentino Rossi's father Graziano (his Honda team mate in 1982) could have been world champ that year if he hadn't been injured; fondly remembered Joey Dunlop, whom he passed on the last lap to win a round of the old Formula 1 World Championship at Misano; and expressed his belief that Giancarlo Falappa might have been the best motorcycle racer of all time if he hadn't suffered head injuries in a mechanically induced testing accident. Falappa

is still part of the extended Ducati family, and was in atten dance at WDW. posing for photos and signing autographs for the fans who remembered him-and apologizing for not remembering them!

B ut I'm getting ahead of myself, because on the Thursday between DRE and the weekend festivities at WDW, I found myself at a motocross track in

Schianno, near the northern Italian town of Varese where the Cagiva factory (makers of MV Agusta and Husqvarna motor cycles) is based. The Husqvarna Off-Road School (w%t~it. o/froadschool.it) offers courses in motocross, enduro and super moto competition, with tuition cost ing 80 euros (about S 100) and bike rentals avail able for another 80. There were 1 8 students in our class, ranging in age from pre teens on mini bikes to Vets on

Open-classers, the majority teens and early-20-somethings on 125s.

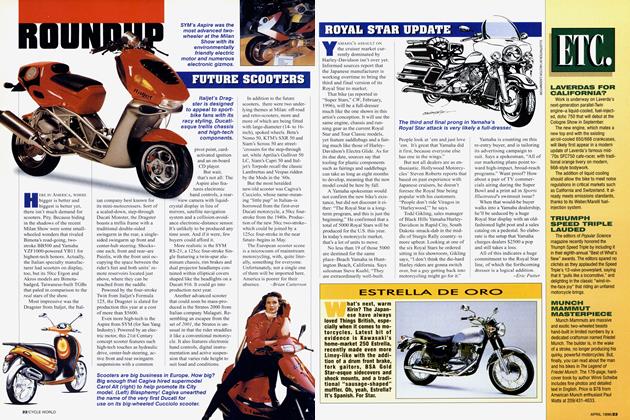

Guest instructor for the day was none other than Alex Puzar, former world champion in the 250cc (1990) and 125cc (1995) classes, and a member of the winning Motocross Des Nations team (2002). Now retired from racing and working as a realtor in Monaco (where he recently sold a home to Ducati MotoGP racer Loris Capirossi), the 35-year-old can still do the business on a dirtbike, with a compact, tidy riding style that reminded me of Jeremy McGrath-whom he claims is a good friend.

Oh, and did I mention that the class was taught in Italian? Fortunately, bnraaap means the same thing in any language, hand signals arc universal (and vital in Italy), and both Puzar and chief instructor Martino Bianchi (whose day job is as Cagiva press officer) speak English, so could translate if I looked lost. Not that they had to: After numerous trips to Italy over the years, my comprehension of the language is pretty solid-it’s not that different from Spanish, after all, and I do live in Southern California. And Martino said that if there were enough interest, classes could be conducted in English.

Compared to the Ducati school, the Husky course was both more and less structured-more in that there was formal instruction with riding drills, and less in that it was extremely low-key, with lessons taught trackside and under an awning in the paddock. No classroom, no garages, no restaurant.

A half-day affair, the school started at 2 p.m. with calisthenics and stretching-always a good idea before riding dirtbikes, especially at my age. We were then sent out to do a few warm-up laps wherein I did my best to learn the undulating I .4-mile circuit on my borrowed Husqvarna TC450.

A classic European-style, natural-terrain motocross track,

Schianno was carved out of a bluff so has numerous steep ascents and descents.

Depending on which sprinklers were sprinkling, the dirt varied from hard-packed to silt to mud, with lots of big, round rocks to make traction even sketchier.

Of course, most of the students were locals who ride this track regularly, so were smoking past me on both sides-a far cry from my Misano experience.

F ollowing our warm-up, we headed to a particularly nasty corner with a steep, bumpy, downhill braking area leading into a silty berm. First, Puzar demonstrated the proper technique, standing on the pegs as he bounded down the hill in complete control, slowing to a crawl as he hit the berm, then sitting down on the front of the seat to let the front tire get a good bite and whacking open the throttle to explode out of the corner. Pros like him make it look so easy!

Then, one by one we attempt ed to duplicate his form, students alternately blowing through the berm after approaching it too fast or tipping over when they hit it too slow. I botched my first two attempts, once stalling the engine and once stewing side ways as I struggled to get a feel

for the Husky's hydraulically actuated clutch. But I nailed it on my third and final attempt, at which point we moved on to jumping.

Having started motocrossing in the pre-Supercross age, I’ve never been big on jumps, particularly doubles and triples, and especially in the wake of the 2001 accident in which I broke my right arm in 20-odd places. I’ve still got a bunch of hardware from that one. Tabletop jumps are no big deal, though, even if the takeoff and landing ramps on this one were pretty steep.

Again, we watched Puzar demonstrate the proper form, holding steady throttle up the jump face, then closing the throttle, stepping on the rear brake to pivot the bike forward in mid-air and landing front-wheel-first at just the right attitude.

I leaned my bike against a dirt embankment while watching him, and shut off the petcock to prevent fuel overflowing the float bowl. Regrettably, I forgot to turn it back on before making my first pass, and so amused my teacher and fellow students by stalling on takeoff and flying maybe

three feet through the air. Oops. I did better with the engine running on successive passes, eventually clearing the obstacle in a graceful arc.

We then headed to another challenging part of the track, a steep downhill leading

into a muddy, rutted, 180degree berm that routed riders right back uphill. Here again, Puzar stressed the importance of being smooth and in control, rather than banzaing it and praying for the best. And again, we students flubbed it one after the other, though thanks to my Husky’s superb brakes, plentiful engine braking and tractable power delivery, I soon had it down.

We continued to work on our cornering skills in a couple of other turns after that, and ended the day by practicing starts in a grassy area at one end of the paddock. Here, Puzar demonstrated how to start in first gear, then kick the shift lever into second with your boot heel as you bring your feet up onto the pegs. After years of starting in second, this was an absolute revelation. Holeshot, here I come!

B y day's end, a few of my peers had come out of their shells and started conversing with me in English. Most want ed to know about Supercross, about who was faster, RC or Bubba, and whether McGrath was

still racing. But one asked a more pointed question: Why would an American travel all the way to Europe to attend a riding school?

A good question, that, and one for which I had no ready answer. The obvious reason is that this was a once-in-a-lifetime (or twice?) opportunity to sample a state-of-the-art motorcycle on a world-class racetrack while receiving instruction from a former world champion. Sure, I could have done that somewhere in the U.S.-in fact I have, and probably will again in the future. But by traveling to Italy, my trip became something of a pilgrimage, the ultimate quest to improve my riding skills.

It was only after I returned home and got thinking about my trip that I realized by taking both motocross and roadrace schools in the same week, I’d reinforced my long-held belief that motorcycles are motorcycles. Riding techniques may vary, but the basic skills are the same, and so readily transfer from one discipline to another. If you feel you’ve mastered one, there’s always another. Education is a neverending process. U

View Full Issue

View Full Issue