HONDA RUNE

Every decade or so, Honda flexes its muscles and kicks sand in the face of its competition. This time around, though, it's not with engine technology.

STEVE ANDERSON

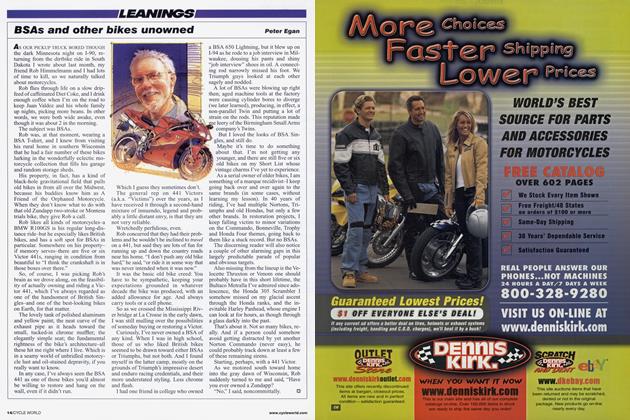

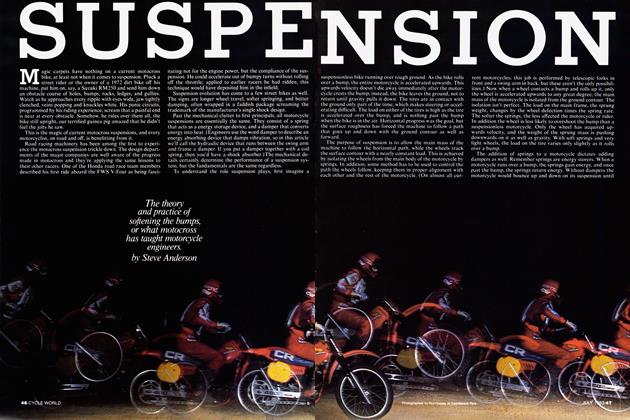

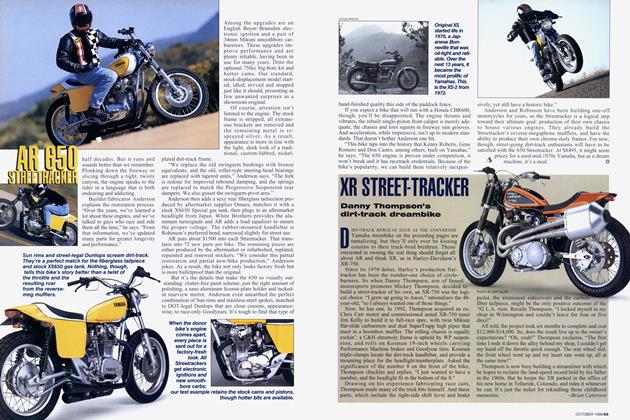

THE CB750. THE CBX. THE CX500 Turbo. The NR750. Every so often, Honda produces a motorcycle that is pure corporate testosterone, a declaration about who is really at the top of the two-wheel food chain. "See this bike and quake," is the statement to its competitors. "We can design and build anything,. just because we want to."

The latest addition to that extremely select list is the Rune, and it's also a first. While every one of its predecessors was about record-setting engine technology-the first mass-production Four of the modern era, the first Japanese inline-Six, the first mass-production turbo with sophisticated electronic controls, the first (and last) production oval-piston engine-the Rune makes do with a visually enhanced and only slightly torquier version of the 1832cc flat-Six that has powered Gold Wings for the last three years. No, the Rune isn’t about engine technology. It’s about style and appearance. It’s the Honda showbike that made it to the production line with all its character intact.

The Rune had a long and complex gestation. According to Ray Blank, VP of Motorcycles for American Honda, its roots reach back to off-site meetings at Laguna Seca Raceway held more than a decade ago and attended by employees from American Honda and Honda Research of America (a separate market research and design company owned by Honda). Blank says that the puipose of those meetings was to answer two questions: 1 ) In a production setting, what is a custom motorcycle? 2) Does Honda have a custom motorcycle? “At the time, we didn’t feel we had à custom machine that was exclusively our own,” Blank remembers.

After that, Honda derived the six-cylinder Valkyrie from the first six-cylinder Gold Wing, resulting in a unique machine that developed a loyal following. When the GL1800 Gold Wing replaced the GL1500, most assumed Honda would upgrade the Valkyrie, as well. But, says Blank, the replacement had to be something special. Honda was watching a limited market develop for $30,000-plus customs built on Harley-Davidson platforms, machines designed by true custom builders. The dream was to move the Valkyrie’s successor in that direction as far as possible to become the ultimate contradiction in terms: a true production custom.

That was what Martin Manchester, head of motorcycle design at HRA, was charged with creating. The design teams came up with three initial directions, prosaically labeled Tl, T2 and T3. Tl was a Valkyrie hot-rod. Many of its styling cues, notes Manchester, went into the VTX series, “diluting the styling strength.” The T3 was a more drag-style custom, fitted with an externally exposed, round-tube frame. But it was the T2 that fired up the designers. It had a 1930s streamline moderne theme that Manchester describes as “Neo Retro.” It very much picked up on the interplay between those early designs, and what modem hot-rod car builders do

to those traditional shapes. The T2 had full fenders for the “slammed” look, a low, long appearance that can be readily seen at such venues as the Oakland Roadster show, where cars are lowered so much that their fenders all but hide their tires. Similarly, the T2’s radiator grill, a complex and curvaceous form, picked up on the 1930s automotive themes.

The T2’s visually complex trailing-link front suspension was derived from the Honda Zodia, a 1995 showbike that had been far too radical for production, but inspired American Honda to push the envelope farther for the Valkyrie replacement. On the Zodia, the trailing-link front stmts were an even more

outrageous design element, with a flowing, scimitar-like shape. On the T2, the designers dialed that back a bit and made each stmt look like a fork leg with a false step mirroring the interface between a conventional tube and slider. And they raked the tubes far more extremely than the steering head, the same trick Harley used on the VRod to give it an extremely raked-out look without achieving tme chopper anti-handling.

There were obviously different factions within Honda pushing for alternative designs. The Tl hot-rod was easy for the non-Americans to understand, and relatively easy to put into production. According to Masanori Aoki, the engineer who served as the LPL (Large Project Leader) on the Rune and the man responsible for moving the Valkyrie replacement from concept to production, “We were hoping the Tl mock-up would be the most popular [at the 2000 Cycle World motorcycle show in Long Beach, California] because new-model development had already begun based on the Tl. But people at the show who saw the T2 mock-up expressed a most unusual degree of excitement. The customer response was so strong it was difficult for many Japanese to understand such enthusiasm. The T2 was more than four times more popular than any of the other designs. It was far and away the overwhelming favorite.”

The enthusiasm at the show and in Honda focus groups cemented the decision:

Honda would build the Rune based on the T2 design. According to Blank, “R&D said the bike couldn’t be built on an assembly line, and that dealerships couldn’t service it. But to be a Honda, it had to be serviceable, reliable, something you can ride in a torrential downpour.” Eventually, Blank says, word came down from the top that the crazies at American Honda “were dreaming, and that’s what we want them to do. We want to build the Rune.” The only problem was in figuring out how.

That was Aoki’s job. He lists 11 new technologies that Honda had to create or adapt to make the Rune producible. Some were relatively straightforward, such as the steelbraided brake lines and throttle cables (watch for those on other Honda models, says Aoki). Others were more involved, such as the chrome-plated wheels that are still giving the production department headaches with high rejection rates. But there were also a few fundamental difficulties in translating the T2 design-it had been done by stylists with little engineering input, after all-into a running motorcycle.

“I thought it would be impossible to mass produce without changing the styling design,” says Aoki. “As an engineer, I thought the process was completely backward.” Honda usually engineers motorcycles, and then gives the stylists engineering constraints under which to work. For the Rune, the process was exactly opposite.

The three main issues that had to be dealt with were the cooling system, riding position and exhaust. The radiator size the stylists had chosen was adequate for 22 horsepower, slightly less than the 118 the Rune is said to produce. It had to grow, but careful work by the designers in cooperation with the engineers preserved the T2’s general look while yielding the necessary greater cooling capacity. The riding position was more troublesome. The designers had given the T2 a boomerang-shaped aluminum handlebar/wing that also incorporated the instruments. The low, stretched-out look and sixcylinder engine placed the rider well back on the machine, so anyone on the T2 had to reach and lean far forward. It was not a riding position that was going to work for a cruiser. But the boomerang bar looked awful if it were stretched to bring the grips back farther. This is one area where the designers gave way, opting for a conventional handlebar and relocating the speedometer into a recess in the gas tank. The short, triangular exhausts were a key of the T2 design, and it was here the stylists refused to compromise. So, Aoki and his team found engineering solutions, including an amazingly expensive one: The difficult-to-form muffler end caps are one-piece investment castings, surely a first for a motorcycle muffler. In the end, engineering and manufacturing at Honda moved mountains to keep the Rune true to the T2 design.

Of course, all of this meant the Rune was not really a Valkyrie replacement, because the no-compromise design pushed the price ($24,499 base, $26,999 with chromed wheels) out of Valkyrie territory. And even then, when asked if Honda was likely to make a profit on the Rune, Blank snorts, “God, no!” The Rune will be produced in sufficient quantity to fulfill existing deposits and so that every dealer will receive at least one, but it’s not intended to be a volume leader. Blank even hints that it might only be produced for a couple of years. It’s about making a statement.

So, what’s this statement like to ride? First, the Rune looks different in metal than in the pictures: smaller, lower and longer, and incredibly well-finished and detailed. When you sit on it,

you it feels lighter than its 794-pound claimed dry weight, and you notice immediately how low the 27.2-inch seat actually is. The engine fires instantly and revs quickly. If you listen closely, you can tell that Aoki was having fim with the exhaust; he’s routed the pipes from cylinders 4-5-2 to the left muffler, from cylinders 3-6-1 to the right, which means three impulses reach the left followed by three impulses hitting the right for the closest approximation to a V-Twin beat that any Six will ever make.

That said, the Rune doesn’t run like any V-Twin. Six individual throttle bodies help it make more mid-range torque than a Gold Wing (which makes do with two throttle bodies). It pulls hard from absurdly low rpm-you can lug it well below 1000 rpm in top gear and still pull smoothly away-and then revs out harder yet. Carrying as much weight as it does, the Rune is not going to be fast by sportbike standards, but it feels quick and strong compared to any cruiser this side of a Yamaha V-Max. And it almost goes without saying that the Six is eerily smooth.

The first thing you notice as you ride away is the immense length that stretches out in front of you; there’s almost the full length of a Buell Lightning starting at the rear of the Rune’s seat and extending to the tip of its headlight. There’s very much the feel of steering a large ship with a tiller, and it takes more than a few turns to get used to that. But the Rune rolls easily in response to slight bar movements, and once you adapt to its unique characteristics, handling is reliable and stable. You can feel the massiveness of the front suspension in very low-speed maneuvers, much as you feel the added weight of the Springer front end on the Harley Softails that are equipped with it.

On the road in top gear, you can admire yourself in the handlebar clamp, which has a convex, shiny surface that mirrors the rider’s head perfectly. Top-gear roll-ons are fearsomely quick. This is one machine you won’t bother to shift often. The riding position remains somewhat compromised by the design, with the pegs rather close and even the longer bar on the chromed-wheel version requiring a very slight forward lean. Similarly, relatively short suspension travel leads to a ride that’s adequate most times, but harsh over larger or sharper-edged bumps.

Overall, though, the Rune impresses with how seamlessly it goes about normal motorcycle business. The fuel-injection provides smooth response, the linked brakes stop the machine strongly and securely, and the handling, within the 32-degree lean limits allowed by the low design, is confidence-inspiring. The Rune may be an attempt to build a true custom, but it remains a Honda first and foremost.

The Rune, then, is a visual statement that works as a motorcycle. It’s a stylistic extreme, and will attract some riders as strongly as it repels others. This is exactly what Honda intended. The Rune says Honda can build a true custom that, by definition, is not going to be the machine for everyone. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue