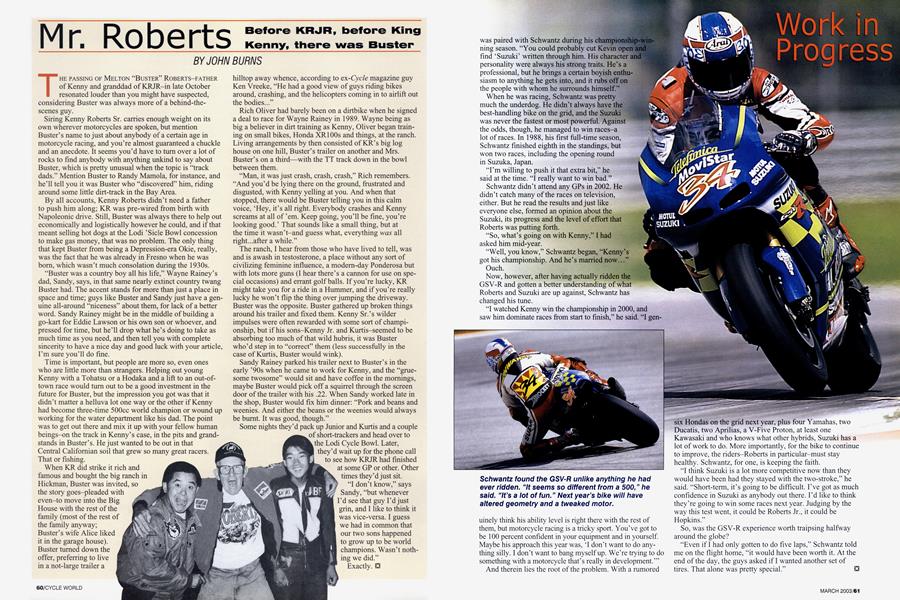

Mr. Roberts

Before KRJR, before King Kenny, there was Buster

JOHN BURNS

THE PASSING OF MELTON "BUSTER" ROBERTS—FATHER of Kenny and granddad of KRJR—in late October resonated louder than you might have suspected, considering Buster was always more of a behind-the-scenes guy.

Siring Kenny Roberts Sr. carries enough weight on its own wherever motorcycles are spoken, but mention Buster’s name to just about anybody of a certain age in motorcycle racing, and you’re almost guaranteed a chuckle and an anecdote. It seems you’d have to tum over a lot of rocks to find anybody with anything unkind to say about Buster, which is pretty unusual when the topic is “track dads.” Mention Buster to Randy Mamola, for instance, and he’ll tell you it was Buster who “discovered” him, riding around some little dirt-track in the Bay Area.

By all accounts, Kenny Roberts didn’t need a father to push him along; KR was pre-wired from birth with Napoleonic drive. Still, Buster was always there to help out economically and logistically however he could, and if that meant selling hot dogs at the Lodi ’Side Bowl concession to make gas money, that was no problem. The only thing that kept Buster from being a Depression-era Okie, really, was the fact that he was already in Fresno when he was bom, which wasn’t much consolation during the 1930s.

“Buster was a country boy all his life,” Wayne Rainey’s dad, Sandy, says, in that same nearly extinct country twang Buster had. The accent stands for more than just a place in space and time; guys like Buster and Sandy just have a genuine all-around “niceness” about them, for lack of a better word. Sandy Rainey might be in the middle of building a go-kart for Eddie Lawson or his own son or whoever, and pressed for time, but he’ll drop what he’s doing to take as much time as you need, and then tell you with complete sincerity to have a nice day and good luck with your article, I’m sure you’ll do fine.

Time is important, but people are more so, even ones who are little more than strangers. Helping out young Kenny with a Tohatsu or a Hodaka and a lift to an out-oftown race would turn out to be a good investment in the future for Buster, but the impression you got was that it didn’t matter a helluva lot one way or the other if Kenny had become three-time 500cc world champion or wound up working for the water department like his dad. The point was to get out there and mix it up with your fellow human beings-on the track in Kenny’s case, in the pits and grandstands in Buster’s. He just wanted to be out in that Central Californian soil that grew so many great racers. That or fishing.

When KR did strike it rich and famous and bought the big ranch in Hickman, Buster was invited, so the story goes-pleaded with even-to move into the Big House with the rest of the family (most of the rest of the family anyway; Buster’s wife Alice liked it in the garage house). Buster turned down the offer, preferring to live in a not-large trailer a

hilltop away whence, according to zx-Cycle magazine guy Ken Vreeke, “He had a good view of guys riding bikes around, crashing, and the helicopters coming in to airlift out the bodies...”

Rich Oliver had barely been on a dirtbike when he signed a deal to race for Wayne Rainey in 1989. Wayne being as big a believer in dirt training as Kenny, Oliver began training on small bikes, Honda XRlOOs and things, at the ranch. Living arrangements by then consisted of KR’s big log house on one hill, Buster’s trailer on another and Mrs. Buster’s on a third—with the TT track down in the bowl between them.

“Man, it was just crash, crash, crash,” Rich remembers. “And you’d be lying there on the ground, frustrated and disgusted, with Kenny yelling at you. And when that stopped, there would be Buster telling you in this calm voice, ‘Hey, it’s all right. Everybody crashes and Kenny screams at all of ’em. Keep going, you’ll be fine, you’re looking good.’ That sounds like a small thing, but at the time it wasn’t-and guess what, everything was all right...after a while.”

The ranch, I hear from those who have lived to tell, was and is awash in testosterone, a place without any sort of civilizing feminine influence, a modern-day Ponderosa but with lots more guns (I hear there’s a cannon for use on special occasions) and errant golf balls. If you’re lucky, KR might take you for a ride in a Hummer, and if you’re really lucky he won’t flip the thing overjumping the driveway. Buster was the opposite. Buster gathered up broken things around his trailer and fixed them. Kenny Sr.’s wilder impulses were often rewarded with some sort of championship, but if his sons-Kenny Jr. and Kurtis-seemed to be absorbing too much of that wild hubris, it was Buster who’d step in to “correct” them (less successfully in the case of Kurtis, Buster would wink).

Sandy Rainey parked his trailer next to Buster’s in the early ’90s when he came to work for Kenny, and the “gruesome twosome” would sit and have coffee in the mornings, maybe Buster would pick off a squirrel through the screen door of the trailer with his .22. When Sandy worked late in the shop, Buster would fix him dinner: “Pork and beans and weenies. And either the beans or the weenies would always be burnt. It was good, though.”

Some nights they’d pack up Junior and Kurtis and a couple of short-trackers and head over to the Lodi Cycle Bowl. Later, they’d wait up for the phone call to see how KRJR had finished at some GP or other. Other times they’d just sit.

“I don’t know,” says Sandy, “but whenever I’d see that guy I’d just grin, and I like to think it was vice-versa. I guess we had in common that our two sons happened to grow up to be world champions. Wasn’t nothing we did.” Exactly.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontResurrection, Inc.

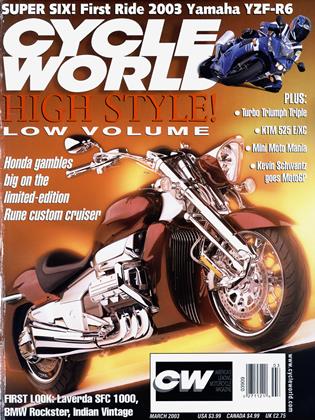

March 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsFamous Harley Myths

March 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

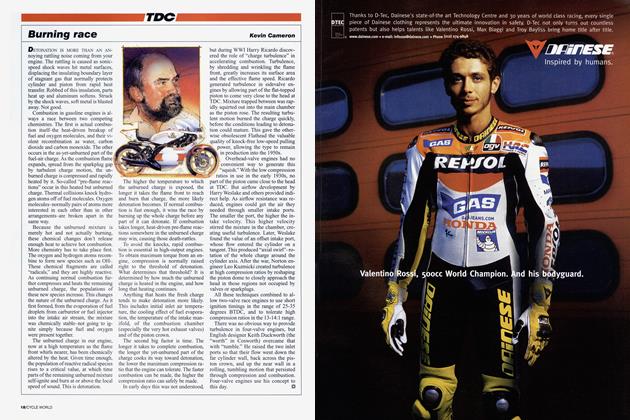

TDCBurning Race

March 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

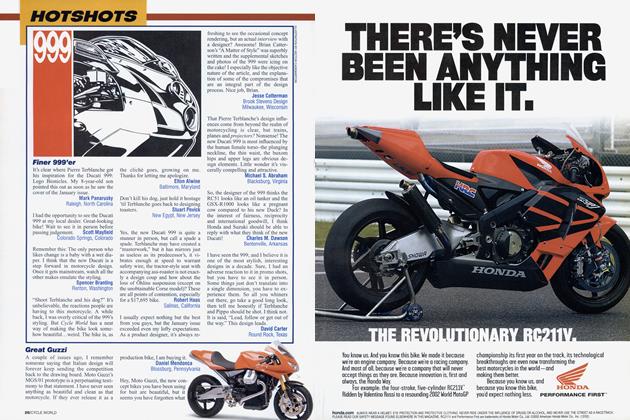

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2003 -

Roundup

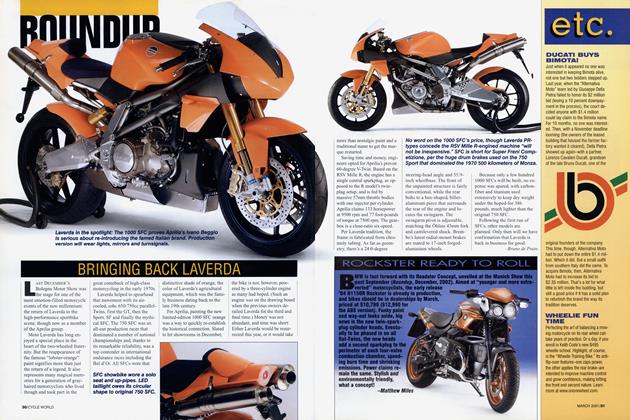

RoundupBringing Back Laverda

March 2003 By Bruno De Prato -

Roundup

RoundupRockster Ready To Roll

March 2003 By Matthew Miles