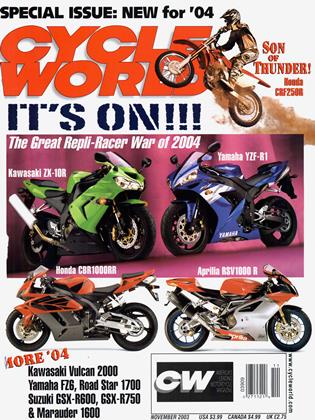

WAR OF THE REPLI-RACERS

.04newrides

We’ve seen the future, and it’s in a hurry

STEVE ANDERSON

THERE WAS A TIME WHEN MOTORCYCLISTS ACTUALLY thought that a Honda CBX might be the end of the line for two-wheel performance. The government and the manufacturers just had to put an end to the performance race, the thinking went. After all, mid-11-second quarter-mile times were just too fast for mere humans. A decade of escalation later, in 1990, the new end of history was to have been the Kawasaki ZX-11, one of which a well-known motorcycle engine-builder actually bought and left in the crate because he just knew there wouldn’t be faster production bikes made. Fast-forward another 13 years and we arrive at the latest candidates for the performance peak: Kawasaki’s brand-new ZX-10R and Yamaha’s revised-from-the-tire-patch-up YZF-R1.

These two machines are amazingly similar in some ways, and along with the new-for-2004 Honda CBR1000RR (see page 42) and current Suzuki GSX-R1000, define a new class of machines: the Universal Japanese Repli-Racer, or UJRR for short. That similarity is understandable, given that they’re tailored to the new realities of Superbike ruleswhich encourage lOOOcc Foursand given the tendency for convergence in high-performance Japanese motorcycle designs. Both the Kawasaki and Yamaha are targeted directly at the recent sales-hit GSX-R, and both manufacturers are dropping hints of outrageous performance: rear-wheel horsepower numbers in the mid-to-high 150s, combined with ready-to-ride weights barely exceeding 400 poundslighter than some 600s, in other words. Between the diets

and gains in muscle, both promise almost a 20 percent power-to-weight improvement over the first Rl, which is about as excessive as strapping a JATO rocket to an F22. Both machines are powered by extremely compact, allnew inline-Fours. Both mount accessories on auxiliary shafts, the better to keep the crankcases as narrow as possible (the new Yamaha engine is 2 inches narrower than the ’03 model) and to allow their engines to be mounted low and forward. Both use gearboxes with stacked input and output shafts, just as the first Rl did, to minimize engine length and allow the longest possible swingarms. The cylinders lean forward, providing a straight path for downdraft

intake systems. (Yamaha engineers have pushed this farthest, tilting the Rl’s cylinders 40 degrees from vertical, 10 degrees more than its predecessor, and almost as much as the first FZ750 Genesis engine.) While bore/stroke figures for the ZX-10R weren’t immediately available, its ability to rev to 12,000 rpm and beyond unmasks its big-bore, shortstroke design. Similarly, the new Yamaha motor bumps bore size up by 3mm over last year’s to 77mm, while stroke shortens from 58mm to 53.5mm. Again, the oversquare design allows a high redline (13,750 rpm indicated on the tachometer) and the big power possible from high revs. Likewise, chassis designs of the two machines have a cer-

tain déjà-vu quality. Both wrap large fabricated aluminum beams tightly around their engines, which bolt in rigidly to reinforce the structure without cradling downtubes. Yamaha claims the same 54.9-inch wheelbase for the R1 as in the previous year, while a quick measurement in our photo studio scaled the Kawasaki’s wheelbase at 55.5 inches. The ZXlOR’s swingarm uses a fabricated structure on the right side, while the left side makes do with an extruded arm with a reinforcing brace for chain clearance. The steering rake on the Kawasaki measures a steep 23.5 degrees, while Yamaha claims 24 degrees. See what we mean by convergence? Similarly, both use the latest radially mounted brake calipers

at the front, with Yamaha topping the trendiness wars with what appears to be a Grand Prix-spec Brembo radial master cylinder, as well. Both bikes have large, curved radiators that provide a much better flow path and more effective cooling. But certainly important details are different. While both bikes use beautifully fabricated titanium exhaust systems (remember when aftermarket companies sold less-refmedlooking Ti systems for $2500?), the Kawasaki’s is a conventional 4-2-1 design with a large muffler on the right side. The Yamaha exhaust reaches up through the swingarm to feed twin mufflers under the seat, leaving the sides of the bike as free from muffler clutter as a Buell, Ducati 999 or Honda

CBR. That left room for Yamaha to position the swingarm bracing low rather than high, creating an airy-looking back end and helping to lower the Rl’s center of gravity. And while both machines have ram-air systems that feed through the frames, the Kawasaki system is particularly elegant with a large central tube flowing air through and around the steering head, with the frame volume acting to significantly increase airbox capacity. Kawasaki set the goal of making the new 10R the lightest machine (as well as the most powerful) in its class, and that surely drove many decisions, some apparent, some far less so. It’s not

hard to see that the wavestyle front discs are slightly smaller than the more conventional discs on the Yamaha (300 versus 320mm, respectively), but other design decisions are almost invisible, such as the linerless cylinder block integrated with the top case half that saves 2 pounds, or the camshafts that Kawasaki machines from billet to save a half-pound over cast cams. (Interestingly, Yamaha retreated from integrating cylinder block from case top in the new Rl, citing the ease of a possible big-bore block!) Six-spoke wheels were chosen because the closer spacing allowed a thinner rim, helping to reduce unsprung weight or, in Kawasaki’s words, “to be practically as light as race-specific wheels.” And one look at the compact analog tachometer with digital speedometer readout in one tiny package tells that the 1 OR must have some of the lightest instrumentation available. To achieve its acceleration goals, Kawasaki turned to designs equally obvious or subtle. The new engine is very much a dry/wet-sump design, with a rectangular sump extending forward from the crankcases, the better to keep the oil far away from the crank to reduce windage losses. Large, 43mm Keihin throttle bodies and finely atomizing fuel-injectors feed a new four-valve cylinder head, one with

highly optimized port shapes. Single, oval-cross-section valve springs with aluminum retainers keep weight low for high-speed operation. Both the intake and exhaust system have computer-controlled butterfly valves to fatten the powerband and allow the use of cams with more overlap. Just as important as horsepower for high-speed acceleration is low drag. To achieve that, Kawasaki’s engineers kept the new 10R compact, with less frontal area than the ZX-6RR. Even the fuel tank has a concave top to allow the rider to tuck in farther. The six-speed transmission is particularly close-ratio, and a back-torque-limiting clutch helps reduce wheel hop during hard braking or quick downshifts. The racing intent of the 10R is clear when Kawasaki notes that optional springs, spring retainers and shims will be available to fine-tune the back-torque function of the clutch for specific conditions.

Yamaha’s goals for the new Rl were phrased slightly differently than Kawasaki’s (not “most powerful and lightest,” but to be the “best, most exciting supersport motorcycle to ride”), but the intent was similar: a quicker, faster, betterhandling and better-looking machine than last year’s Rl, and one that would spank a Suzuki GSX-R1000. The translation of those goals into specific engineering language led to some amazing targets: 172 horsepower at the crankshaft (180 when the ram-air is working at speed), and a dry weight of just 378 pounds-targets that Yamaha claims to have met. To do that, the new engine was required. It retains a classic Yamaha five-valve-per-cylinder combustion chamber, but more oversquare cylinder dimensions required the valve-included angle to be tightened once again to actually increase compression with undomed pistons. Smaller diameter camshafts reduce weight while providing

more lift and duration. And while piston speeds for the new Yamaha engine have reached the stratosphere at the indicated redline (over 4700 feet per minute), one of the secrets of Open-class sportbikes is that their engines can be run a lot closer to the edge than those of 600s or smaller machines because no rider on any road in the world can use them at full power but for a tiny fraction of his riding time.

The new frame is more compact and more rigid than its predecessor, and while it’s not made using Yamaha’s much vaunted Controlled Fill casting process, the swingarm and subframe are created using that technology, which allows much thinner wall thicknesses and results in lighter weight components. (It’s also used for engine components.) Similarly, newly designed five-spoke wheels shave 10 percent from the weight of last year’s hoops. The big front brake discs may have grown by 20mm this year, but they’ve also been thinned by 10 percent to 4.5mm to keep weight low.

Of course, neither Yamaha nor Kawasaki wanted to stop with just improving the performance of their liter-class leaders; they wanted them to look swoopier, as well. The approaches were somewhat different, with Kawasaki relying on the sharp angular styling given

its GP machine this year, and a distinctive large central ram-air scoop for a unique and aggressive face. The Rl, meanwhile, is most distinguished by its pointed nose and airy appearance at the rear, with almost no hardware filling the area immediately above the rear tire. With four headlights and two running lights, the front view of the Yamaha is unique, remaining symmetrical with one low and one high beam on each side. The Kawasaki lights just one light per side at a time, depending on whether you’re on low or high. The detail design of both machines is relatively stunning, with hardware that looks like it came from a recent GP machine. Particularly nice are the exhaust headers on both bikes, their LED taillights, the through-the-frame shift linkage on the Yamaha, and the wave front discs of the Kawasaki.

Of course, as with every other escalation of the performance wars, there will be those who’ll ask, “Who needs this level of performance?” The answer to that is simple: No one needs a 400-pound motorcycle with almost 160 horsepower, a motorcycle capable of accelerating through the quartermile in less than 10 seconds. Absolutely no one needs a motorcycle with a top speed pushing 180 mph or more. No one needs a motorcycle that will snap upright into a wheelie every time you accelerate out of a tight comer. Nah, no one needs any of that.

But there are plenty of motorcyclists out there who want it, and the Japanese motorcycle companies are

working harder than ever to meet not just our needs, but to fulfill our wildest dreams. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontRoad Man

November 2003 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsBoogie Music & Them Mean Old Biker Blues

November 2003 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCDodging the Dragon

November 2003 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2003 -

Roundup

RoundupJesse James, Inc.

November 2003 By Mike Seate -

Roundup

RoundupAnti-Dive Alive!

November 2003 By Mike Keller