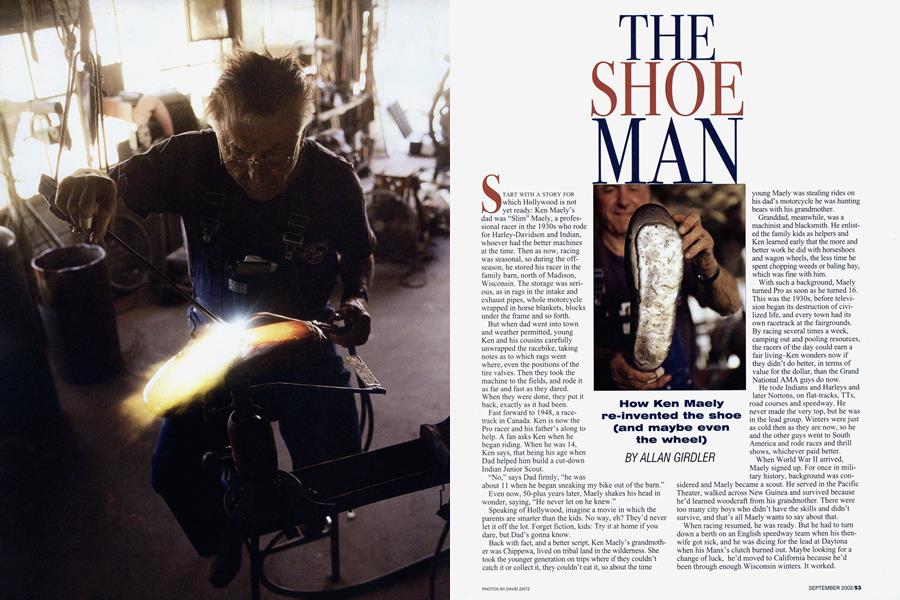

THE SHOE MAN

How Ken Maely re-invented the shoe (and maybe even the wheel)

ALLAN GIRDLER

START WITH A STORY FOR which Hollywood is not yet ready: Ken Maely’s dad was “Slim” Maely, a professional racer in the 1930s who rode for Harley-Davidson and Indian, whoever had the better machines at the time. Then as now, racing was seasonal, so during the offseason, he stored his racer in the family barn, north of Madison,

Wisconsin. The storage was serious, as in rags in the intake and exhaust pipes, whole motorcycle wrapped in horse blankets, blocks under the frame and so forth.

But when dad went into town and weather permitted, young Ken and his cousins carefully unwrapped the racebike, taking notes as to which rags went where, even the positions of the tire valves. Then they took the machine to the fields, and rode it as far and fast as they dared.

When they were done, they put it back, exactly as it had been.

Fast forward to 1948, a racetrack in Canada. Ken is now the Pro racer and his father’s along to help. A fan asks Ken when he began riding. When he was 14,

Ken says, that being his age when Dad helped him build a cut-down Indian Junior Scout.

“No,” says Dad firmly, “he was about 11 when he began sneaking my bike out of the bam.” Even now, 50-plus years later, Maely shakes his head in wonder, saying, “He never let on he knew.”

Speaking of Hollywood, imagine a movie in which the parents are smarter than the kids. No way, eh? They’d never let it off the lot. Forget fiction, kids: Try it at home if you dare, but Dad’s gonna know.

Back with fact, and a better script, Ken Maely’s grandmother was Chippewa, lived on tribal land in the wilderness. She took the younger generation on trips where if they couldn’t catch it or collect it, they couldn’t eat it, so about the time

young Maely was stealing rides on his dad’s motorcycle he was hunting bears with his grandmother.

Granddad, meanwhile, was a machinist and blacksmith. He enlisted the family kids as helpers and Ken learned early that the more and better work he did with horseshoes and wagon wheels, the less time he spent chopping weeds or baling hay, which was fine with him.

With such a background, Maely turned Pro as soon as he turned 16. This was the 1930s, before television began its destmction of civilized life, and every town had its own racetrack at the fairgrounds. By racing several times a week, camping out and pooling resources, the racers of the day could eam a fair living-Ken wonders now if they didn’t do better, in terms of value for the dollar, than the Grand National AMA guys do now.

He rode Indians and Harleys and later Nortons, on flat-tracks, TTs, road courses and speedway. He never made the very top, but he was in the lead group. Winters were just as cold then as they are now, so he and the other guys went to South America and rode races and thrill shows, whichever paid better.

When World War II arrived, Maely signed up. For once in military history, background was considered and Maely became a scout. He served in the Pacific Theater, walked across New Guinea and survived because he’d learned woodcraft from his grandmother. There were too many city boys who didn’t have the skills and didn’t survive, and that’s all Maely wants to say about that.

When racing resumed, he was ready. But he had to turn down a berth on an English speedway team when his thenwife got sick, and he was dicing for the lead at Daytona when his Manx’s clutch burned out. Maybe looking for a change of luck, he’d moved to California because he’d been through enough Wisconsin winters. It worked.

Ken Maely’s major claim to racing fame began, of all odd places, at the Marine Stadium in Long Beach.

But first, tradition says the notion of putting steel between boot and track first took hold in Australian speedway in the 1930s. Speedway went international and the idea caught on. The first American standard in the mid-1940s was one end of a ’34 Ford bumper. The ends curled up, which made for a toe, sort of, while the bumpers were cheap and the junkyard close. But such a plate weighed 8 pounds and would last only a couple of weeks.

Maely used the bumpers like everyone else, but he had racer, adventurer and blacksmith genes. Watching boat races one day, he observed the hulls skimming over the surface, and thought, “Of course! Why don’t I shape a shoe like that?” He knew metals, so he experimented and came up with bandsaw blades, made in high-carbon steel.

The shape wasn’t that hard to forge, and the shoe worked. Ed Kretz (among others) borrowed Maely’s shoe and asked him to make another. In 1950, Harley-Davidson asked him to outfit the entire team, and Ken Maely became “The Shoe Man.”

The record speaks for itself: “Since 1952, every national champion has done it with a Maely shoe.”

In detail, it’s not that simple, of course. The shoe has to have the best steel, and there’s a coating, the equivalent of secret sauce, and the curvature varies-speedway slides aren’t like mile slides-and over the 50 years there have been modifications and improvements. Maely has a contractor making

boots to partner the shoes now, so he and his helpers can use a semi-production line. (He also has testimonials from racers who say they were back of the pack until they got his new boots and shoes, and now they’re on the box, but as they say in the prospectus, your results may vary.)

In the mid-1970s, when speedway racing was big in California and he’d retired from the flat-track circuit and had time and energy to spare, Maely designed and produced, in limited numbers, his own speedway engine. The rules allowed 500cc, one cylinder and any fuel that’d bum, and the standard speedway powerplant was a pre-war design.

The Maely Mk. 1 was a four-valve, singleoverhead-cam design with the gearbox, clutch and primary drive in unit. He made a batch, they sold and worked, and Husqvama bought the rights to the design so it could get into the four-stroke business again. The contract said Maely couldn’t make any more unit-style Singles, so he designed and built the Mk. 2, which used a jackshaft and bolted-together cases and drive.

Constant readers will recall that when Honda’s VTR1000 V-Twin was introduced in the mid-1990s, designer and engineer Soichiro Irimajiri revealed that one of his secrets from the world-beating Honda GP machines of the 1960s was making the frame with optimum-which isn’t maximum-torsional rigidity.

There were skeptics then, and surely they’re still here. But in the 1970s, Maely made tunable speedway frames. He used two lightweight downtubes, and had a brace from the rear to the steering head. The racer could move the brace

back and forth, tuning the frame to the track’s surface, grip and length. And they won at least their share.

Maely’s next chapter, too, is stranger than fiction. About the time the speedway projects were done, he was hired by the South African government to revise some Honda dirtbikes for military duty. One day he got a call from a cousin working in the courthouse back in Wisconsin: What had Ken done to attract the attention of the Red Chinese government? Maely hadn’t the faintest. Well, said the cousin, a Chinese diplomat just came in and got a certified copy of your birth certificate.

Then Maely got an offer he didn’t refuse. Twenty-some years ago, China was just beginning to open up, and ease up. Chinese manufacturers, which were branches of the Communist government, had been cheerfully copying other people’s cars, trucks and motorcycles, but they needed machines suited to their own situations and they didn’t have the designs or the designers.

What they needed, the guys at the top decided, was a creative blacksmith, someone who could design motorcycles that were repairable and durable.

What they needed was Ken Maely, so they offered a contract. He’d organize a design studio, implement the designs, get paid on

schedule and come home on a regular basis. It worked. The studio Maely created turned out all manner of motorcycle engines, mopeds to military offroaders. The contract expired several years ago but the work continues, as Maely has 38 engineers, draftsmen and support personnel still at work, and he still drops by the office.

“It was the happiest time of my life,” Maely says now, and motorcycles had nothing, well not much, to do with it. Maely’s first marriage had gone bad years before, and in the course of the design project, he met a woman executive in the giant government complex where the team worked.

Rose, as Mrs. Maely’s name translates, was the daughter of a top judge in China, and had earned her doctorate in the equivalent of our ROTC; that is, her tuition had been paid in exchange for a term in government service.

As a government employee, executive or no, she lived in the women’s section of the complex. Maely was housed in the guest section. Fraternization, speaking mildly, was not encouraged. Maely, meanwhile, had learned to speak Mandarin; not tough, he says, if you grew up in a Swiss-Chippewa family with English as a third language.

He and Rose met, chatted, talked and next thing the authorities didn’t know, she’d leave her apartment and ride off on her bicycle, while Maely had ridden away on a motorcycle. They’d rendezvous, she’d hop on the back and they’d ride to the other side of town and dance until dawn.. .sure, they

were acting like teenagers, but they were being treated like teenagers.

Eventually, the situation was too contrived to continue, so Maely renewed his contract with clauses that allowed him to marry Rose, and for her to go with him when he returned to the U.S., and they’ve lived happily ever since.

And that’s why, when you arrive at the Maely estate west of Riverside, the brick wall is labeled “Great Wall of Corona.”

That brings us to Maely’s estate/ home/shop/farm/ track/academy. Fifty years ago, Maely noticed that the Los Angeles area was becoming crowded, so he looked around and found acreage east of the Cleveland National Forest, on the west side of a minor road following a stream from a lake to a river. There were farms, ranches, quarries and miles of open space. So he bought the land and set up shop.

The establishment defies description. It’s nearly impossible to count the buildings, never mind the cars, trucks, bikes, tractors, plows, graders, dozers and mixers.

Following the example of Henry Ford, who devised machinery to escape from the drudgery of farming and then spent the money he made re-creating the family farm he’d fled, Maely began growing food soon as he had the land.

There used to be geese, which led to the place being called the Goose Ranch, although the name on the gate said Hotshoe Manor. But the coyotes made off with the geese so while the sign remains the same, the hangers-on, who are legion as we’ll see, now call the place Maely’s.

Most of the land was

planted with citrus and then Chinese vegetables, odd varieties of something like cucumber mostly, popular at the exotics markets in Los Angeles. Ordinary citrus is now a depressed market, so that land is being replanted with Mandarin oranges, a variety currently in vogue.

But the feature of the place is the track. It’s a practice track. Keep that in mind and remember, loose lips alert urban planners.

When he was a little kid, Maely recalls, he’d be in the grandstand and his dad would be lined up for the start. Dad would see son, and flash the thumbs-up. Maely thought dirt-track motorcycles were the best things on the planet, and he thinks so now.

Among the trades of which Maely is Jack, is heavy construction. He rounded up graders and dozers and built rigs to drag the dirt and found a secondhand water tanker. The dirt in dirt-tracks is more like the rubber in tires than the dirt in your backyard, in that it’s a special mix, science with a dash of art. Ken’s been around dirt-tracks all his life and he’d watched it done right and wrong. He took the equipment and raw materials and the right advice and built as reliable and enjoyable a dirt-track as there is in the U.S., maybe even the world.

It’s small, maybe Vioth mile depending on where the circumference is measured, but that’s on purpose: You can be quick without going very fast. Just about everyone falls down, but hardly anyone crashes, which is really good for confidence and for learning.

Which is what riders of all skill levels have been doing for several decades now. At least four world champions have trained on the track, along with scores of roadrace and dirt-track national riders, and there has been a series of speedway schools.

Naturally, anything as good and useful as this has its enemies. They pose as progress. As in? Note that every time a local airport is closed, a farm is paved or a freeway routed through a scenic area, someone says, “Well, you can’t stop progress.”

In the case of Hotshoe Manor, the original neigh-

bors were quarries, cement plants, truck-service shops, small ranches and coyotes. Then Interstate 15 paralleled the watercourse, and with it came a more serious scavenger, the developer. Housing tracts appeared to the south, and Maely was forced to buy the land to his north, a vacant tract owned by someone who had plans and threatened legal action because Maely’s operation wasn’t as scenic as he’d like.

To say Maely won is to speak in advance of the facts, because in matters like this, faced with greedy opponents and with politics, the threats never stop.

Maely did have the grandfather clause on his side: He was there first and had been operating a legal business for nearly 50 years. At roughly the same time, the cement processor across the creek had to clear out the dirt he’d been working on, and Maely did a deal, acquiring tons of dirt. It’s being moved and compacted and graded, the plan being a new, improved and perhaps a bit larger oval. Local government has allowed that Hotshoe Manor can have a practice track as part of its “agricultural operations,” but racing, in the sense of tickets and prizes and classes, isn’t permitted.

All patrons (make that visitors) need to keep this in mind.

At present, the practice track is in operation and use virtually every day, dawn to dusk. It’s home for Southern California speedway riders, and there are roadracers who visit on off weekends, carrying on the Kenny Roberts

tradition. There are also local flat-trackers getting in some practice, and there’s even an informal group of Honda XR100 riders who congregate on certain afternoons. If you didn’t know better, you’d swear they were racing.

ost important in Maely’s view, are the kids. The first thing people notice when they discover motorcycle .racing is how family-oriented the sport is. At Maely’s, the groups are often two and three generations deep, the support is mutual and no one thinks it odd that a 65-year-old on an XR100 is taking the inside line and keeping ahead of an 8-year-old on a full-size speedway bike inherited from his dad. The kids are everywhere. They are welcome, indeed encouraged.

In the middle of all this is Ken Maely, rumbling around with the water truck or dragging the track, in the company of two huge, ancient dogs sitting in the cab with the boss, proud as peacocks because they’re helping do important work.

Doesn’t get much better than this, as the saying goes, but

what next? That’s the worrisome part. It doesn’t take long to do the math and reckon that someday, even Maely will have to slow down, find someone as keen on bikes and kids and racing as he is, to take over an operation-make that an institution-as unique and as useful as Maely himself.

The Shoe Man’s shoes are gonna take some filling.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue