HAYDEN, HONDA, HORSEPOWER

RACE WATCH

The Daytona 200 as one-man, one-brand show

KEVIN CAMERON

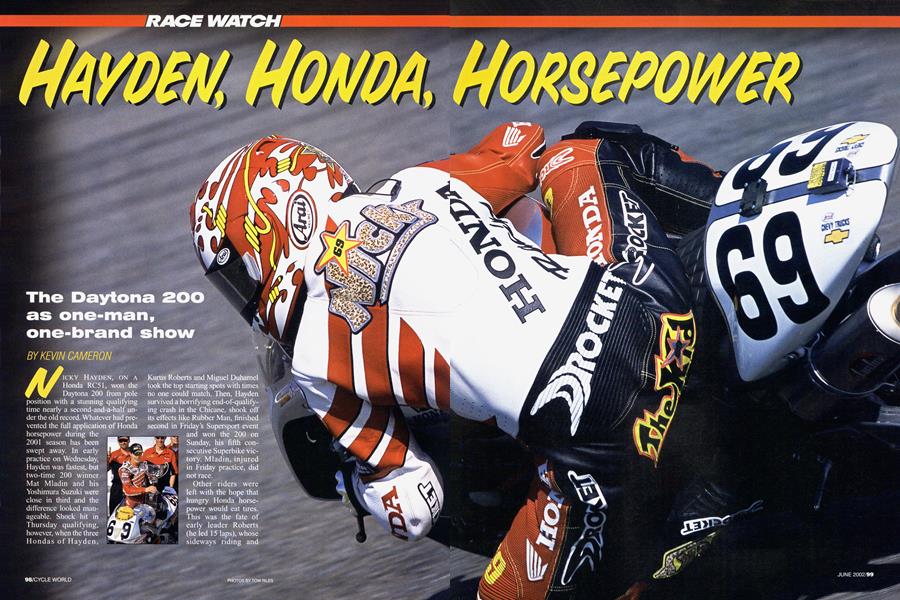

NICKY HAYDEN, ON A Honda RC51, won the Daytona 200 from pole position with a stunning qualifying time nearly a second-and-a-half under the old record. Whatever had prevented the full application of Honda horsepower during the 2001 season has been swept away. In early practice on Wednesday, Hayden was fastest, but two-time 200 winner Mat Mladin and his Yoshimura Suzuki were close in third and the difference looked manageable. Shock hit in Thursday qualifying, however, when the three Hondas of Hayden,

Kurtis Roberts and Miguel Duhamel took the top starting spots with times no one could match. Then, Hayden survived a horrifying end-of-qualifying crash in the Chicane, shook off its effects like Rubber Man, finished second in Friday’s Supersport event and won the 200 on Sunday, his fifth consecutive Superbike vietory. Mladin, injured *n Friday practice, did not race.

Other riders left with the hope that hungry Honda horsepower would eat tires. This was the fate of early leader Roberts (he led 15 laps), whose sideways riding and tire-smoking drives exploded the rubber from his rear tire on lap 23. The whirling tread flaps hammered his exhaust pipe half closed as he dove for the grass, continuing around to pit lane and eventually finished sixth. Did tire vibration give no warning? Next year, Roberts will know how to handle Daytona.

Duhamel’s left foot slipped off a slick footpeg about lap eight. Next time around, he sat up at start-finish and coasted to a stop after Turn 1. Even the famous RC51 electric-starter failed to revive the engine. Post-race, four Japanese technicians found its oil transformed into a “milkshake,” a sign of water contamination from the cooling system or failed engine internals.

Hayden, never challenged after lap 24, was mindful of his tires and led the last 34 laps in the lonely point position, wondering if the race would ever end. A last-lap draft by Yoshimura Suzuki’s Jamie Hacking from third pulled him to second in front of Yamaha’s Anthony Gobert. Aaron Yates (another Yosh Suzuki rider), Eric Bostrom (on the lone Kawasaki) and Roberts completed the factory order, with Andy Deatherage in seventh, heading the overwhelmingly Suzuki-mounted privateers that filled the field.

When it comes to racing, Honda is a strange company, capable of brilliant success as on this day, yet also doggedly devoted to errors it seems to freely choose. In the 2000 season, Colin Edwards rode the then-brand-new RC51 to the World Superbike Championship. When that bike was “improved” for 2001, it mysteriously failed to hook up and accelerate off corners. At Laguna Seca that year, it was possible to watch both WSB and AMA versions of the Honda, and both were visibly stiff at the back-“like a board,” in the words of Edwards. Within just a few laps, these machines were sliding and smoking their tires, helpless on the track despite their superb horsepower. The classic 1960s taught us to expect instant engineering solutions from this powerful company, developed by around-theclock emergency R&D teams, then rushed by air to the race circuit to trample problems in the nick of time. With such a history of “action this day” behind it, why did Honda continue to unworkable chassis combinations? Aí the Italians that much better at chassi engineering? Could it be “internal policy reasons?” We’ve seen other companies do this, try to force a bad idea to work, like a man determined to hai mer nails with his forehead.

It’s not for us to know which it wa¡ lack of understanding or higher corpG| rate purpose. All we know is that Hon» has now changed something so th; both the WSB RC51 and those of ti American Honda squad have much bet? ter drive on corner exits.

And what kept them from hooking u] before? Asking this of the American Honda team gets you vagueness: “Well, it was a lot of things-now we have better fork internals, for one thing...” An» that’s about as good as the informatiV gets. Poor fork internals forced the use of a stiff rear spring, huh? There’s an interesting story here, but it isn’t being told yet.

In addition to the three Honda men, Gobert, HMC Ducati’s Pascal Picotte and Mladin also broke last year’s qualifying record-but by much smaller increments than the Honda crew had. It was as though the 200 had suddenly switched from a two-tier factory/privateer event to a three-tier event composed of the rocket Hondas, then the six slower factory bikes, then the usual many-seconds jump to the fastest of the privateers. Most of the field showed the speed gain you’d expect in a normal year of tire and engine development. The Hondas had gained much more-all the engine power they’d developed in a year’s work but couldn’t use until now.

Aside from chassis considerations, might lOOOcc Twins have an inherent advantage over 750cc Fours? Or is it just that Honda has weathered Japan’s five years of recession better than the ers? A bit of both, I believe. Honda’s ces are strong, and the company afford development the others cannot. Yet on close examination, Twins have advantages. The original FIM Superbike formula gave Twins lOOOcc to make up for the higher rpm potential of the Fours, based upon equal piston speeds. But the real limit to rpm is not piston speed, but piston ring acceleration. Above a certain peak TDC ring acceleration, it becomes difficult to keep the top ring on the bottom of its groove and sealing properly. This variable increases as the square of rpm, but in simple proportion to stroke, so that the longer stroke of Twins is a less strong promoter of high piston acceleration than is the higher rpm of the Fours. ;efore, the Twins can survive higher s than were anticipated by the FIM’s original, piston-speed-based formula.

Another point is that although the two engine types have similar total piston ring seal lengths (a basic measure of friction), the Twin has more displacement with which to push that amount of seal. Also, a Twin has two main and two rod bearings, while an inline-Four has five mains and four rod bearings. As a result, the fourcylinder engine has higher friction loss in proportion to its power. Next, we see from the radiators on Superbikes that Twins (smallish rads) reject less heat to their coolant than do Fours (giant, fairing-filling rads). This is because more of a Twin’s hot combustion gas is far from cooler metal surfaces. That potentially leaves more heat in the Twins’ combustion gas to do useful work-it’s a question of combustion chamber surface to volume ratio.

The idea that the present formula may be one-sided, plus fears of a continuing factory bug-out from racing (there were 40 percent fewer factory Superbikes at Daytona this year), have stimulated sanctioning bodies to emit rumors. How would we like (they seem to ask) a new kind of racing in which engine technology is de-emphasized by giving all engines lOOOcc and holding them to Supersport-style mods only, while chassis development is made much more open? Such racing might be cheaper, might help cash-short Japanese companies to hang in there, might even work if only privateers show up someday (as in 1979-81). Or would it just be different, and therefore present new expenses? As the song says, the future’s not ours (or the FIM’s, or the AMA’s) to see.

Dunlop had three basic tire compounds-a soft one intended for the slow riders whose pace heats tires less, a harder one that most people actually used, and one harder yet as a match to the top riders’ more vigorous use. Early in qualifying, Suzuki’s rear take-offs were showing “pimples”-regularly spaced raised areas on the left-center region of the tread that runs against the banking. This is incipient blistering, the boiling and partial expansion of resins and oils used in tread compounding.

Europeans regard American Superbike racing as an anomaly because Mladin’s Suzuki-a brand long relegated to World Superbike’s second stringhas somehow dominated the AMA series, while WSB has become a “Battle of the Twins.” Much credit for Suzuki’s U.S. success must go to Mladin’s effective, experienced crew. Mladin is a strategist, and his crew is the best there is at finding a good setup quickly. This time, their work availed them little. Slowly, it emerged from the practice rush that the Hondas were really fast. Then, Mladin’s crew began to seek tiny improvements in rear damper and spring-rate changes. As former Honda Team Manager Gary Mathers remarked, “Mladin’s crew has had that bike’s handling worked out for about the past three years, so for them to try all these little changes indicates some desperation.” How hard they were pushing was revealed by how early in qualifying Mladin’s tires were blistering.

The New Gobert was a sight to seetrim, diligent and fast. Circumstance forced him to gear his Yamaha (a bike left over from Yamaha’s exit from WSB) up for drafting. His last-lap position in second, almost 20 seconds behind the leader, left him overgeared and easy game for Hacking’s chicane-to-finishline attack. Being forced to pit six laps early for a failing front tire cost Gobert time that could have changed the race. Daytona is like that. Hacking’s steady performance helps to offset his reputation as a wildman.

Although the Yamaha and Kawasaki > factory teams made their share of practice suspension and tire changes, what stood out was time spent with the computer plugged in, looking for answers. Each was using a new type of Öhlins fork with both highand lowspeed clickers. The idea is to make it possible to just click your way to a good setup, rather than having to disassemble the fork and restack the damping shims for changes to the high-speed damping as with other forks. It was taking time to make the new fork work as well as the old, and Gobert couldn’t wait-one bike was switched back to the earlier Öhlins the team knew, and then he did his best lap time, nearly into the 1:47s with the Hondas, giving him the final frontrow starting position.

This year, the AMA provided section times as well as whole lap times, and these were revealing. Mladin was run-

ning hard through the infield, but from the chicane to the finish line, the Hondas had a crushing acceleration/top speed advantage that amounted to about 0.9

of a second. What would happen once the Honda men began to push harder through the infield?

Harley’s withdrawal from Superbike > racing set Picotte free to ride the HMC Testastretta Ducati, a potent piece. Proving that he still exists, he turned in a 1:48.219 qualifying time to claim fifth starting position. But Picotte had to leave the race on lap 17 with gear-selection trouble. Then, in the weeks following Daytona, HMC made the surprise move of firing the French-Canadian, even after such a promising string of offseason tests and a strong qualifying performance for the 200. His replacement is three-time AMA Superbike Champion Doug Chandler, rideless this season in the face of factory-team downsizing.

Mladin, pushing his moderately powerful Suzuki hard enough to open nasty blisters on his qualifying tires, could only squeeze out a 1:48.311 for sixth on the grid-second row. How the mighty have fallen. Among the Honda men, only Duhamel had serious Q-tire blistering.

Now came the revolution. Onto the Hondas went the Q-tires, and one by one, their riders dropped into the 1:47s. Roberts’ hot lap was scary for all, including himself. Hayden’s stunning 1:47.174 took pole, and trying for an even better time minutes later, his bike high-sided in a big way. Duhamel, in his usual fashion, looked like nothing much until the final three minutes of qualifying, when he fired himself into the number-two slot with a 1:47.259. Experienced Daytona-watchers picked him to win, as the only rider with both speed and deep 200 experience.

The week brought crashes and injury to many-Mladin crashed in Friday practice, taking him out of Sunday’s race after elbow surgery (to remove bone fragments and other debris from a deep abrasion) left him with too little arm strength and too much pain. Duhamel crashed in practice exiting the infield, but was unhurt. Anthony and Aaron Gobert also crashed-the latter being seriously injured-and only Anthony raced.

In these leaner times, technology addicts found little to stare at. Kawasaki had two pipes going into a single muffler, staying separate through it to two outlets. Honda had switched from two mufflers to one on the left, served by a big pipe arched up over the rear tire. Titanium’s propensity to seize to itself made the crew’s frequent muffler changes a wrenching, squeaking job. The new Öhlins fork was distinguished by a small cylinder between the fork leg and caliper mount, said to be a pressure accumulator to prevent damper cavitation. Yamaha left electric starters on through practice, plugging in a booster battery during pit stops. It’s hard to know where ideas begin, but the pistons in Don Tilley’s Buell Pro Thunder race engines now have features known to exist in Formula 1-such as hard-anodized and then solid-lube-impregnated skirts. It is important in all engines to reduce the amount of oil flying around in the crankcase-this makes low-pressure, low-friction oil rings adequate-but skirt galling becomes a problem that hardening and solid lube can address. Locating piston rings high on the piston makes power by reducing charge trapping in ring and land crevice volumes, but it also pushes top-ring-groove temperature to levels that either stick the ring by oil coking or cause it to pick up aluminum from the groove. Either way, sealing suffers. As has been done for many years in GP two-strokes, ring grooves are now being anodized-their surfaces converted to super-hard aluminumoxide ceramic. This mimics the standard diesel practice of casting a hard, heat-resistant nickel-alloy ring belt into soft aluminum pistons. Modern wristpins are very short and thinwalled, requiring them to be made of fatigue-resistant tool steels of the kind used to make the landing gear struts of heavy aircraft. The harder race engineers push, the more traditional design must be propped up by a multitude of little fixes.

In World Superbike, it’s usual for the Honda to have significantly more power than the Ducatis. Is this just because Honda works harder at the power game? Maybe not. Ducati’s 10 WSB tities have come from intimate adaptation of its whole motorcycle to European racetracks-not from sheer Daytona-winning power. It may be that it’s easier for the “valve-spring motors” of Aprilia and Honda to reach high valve lifts than for Ducati’s springless desmodromic mechanism. Current practice lifts valves to 40 percent of valve-head diameter to allow room for spring pressure to stop and reverse the lifting valve. Ducati uses less. Is this by choice, because with positive closure they don’t need to over-lift the valve? Or is it a limitation-because higher lift would require longer closing rockers that would have to be either heavier or flexier than those presently used? These are interesting questions.

Daytona with its high banks and speeds is a unique situation, and Honda had the perfect medicine for it. As racing returns to flatter, twistier circuits, the equation will change unpredictable Will uncaged Honda horsepower continue to work as well as it did on March 10? Whatever the outcome, Nicky Hayden has made a fine start to the championship and has again proven his calm maturity. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontDaytona, Dimming

June 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Steam-Shovel And A Piece of Earth

June 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCAll In A Row

June 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2002 -

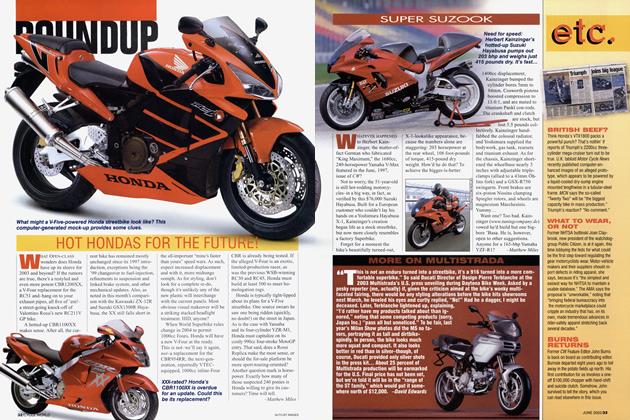

Roundup

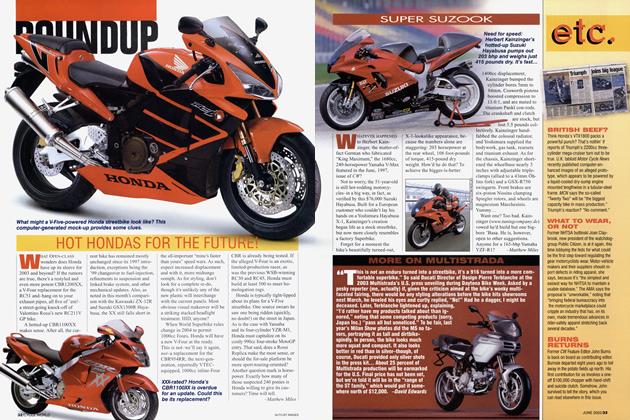

RoundupHot Hondas For the Future!

June 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupSuper Suzook

June 2002 By Matthew Miles