Creative power

Glenn Curtiss: inventor, manufacturer, racer, pilot

KEVIN CAMERON

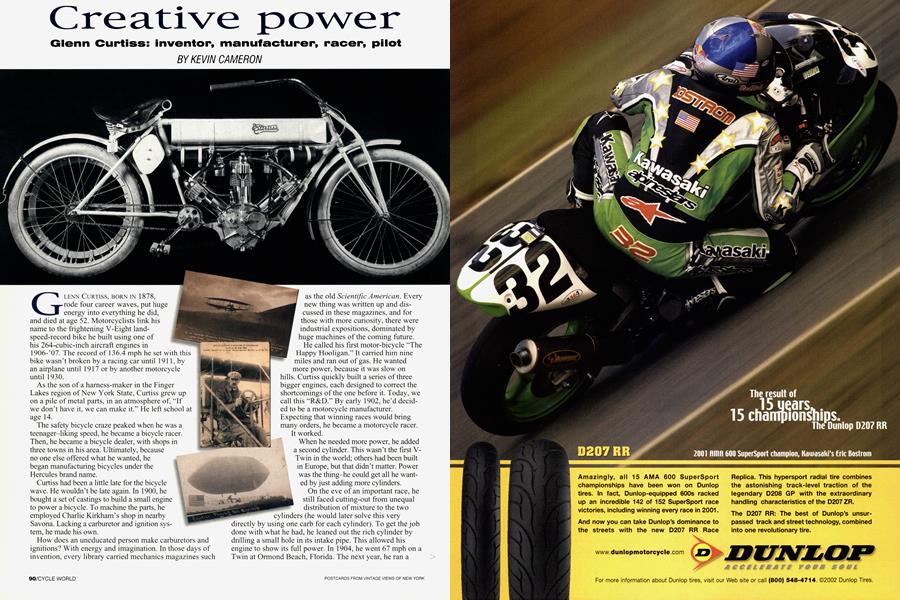

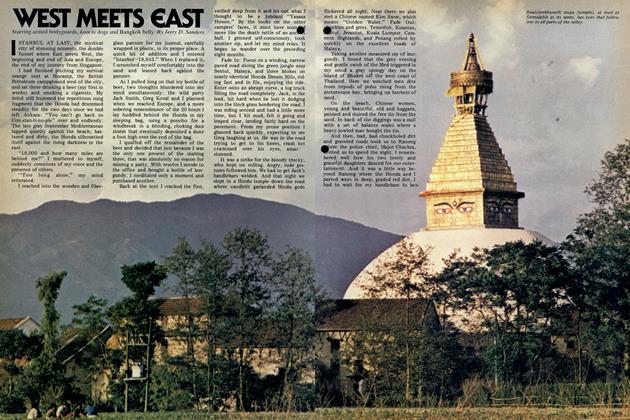

GLENN CURTISS, BORN IN 1878, rode four career waves, put huge energy into everything he did, and died at age 52. Motorcyclists link his name to the frightening V-Eight land-speed-record bike he built using one of his 264-cubic-inch aircraft engines in 1906-’07. The record of 136.4 mph he set with this bike wasn’t broken by a racing car until 1911, by an airplane until 1917 or by another motorcycle until 1930.

As the son of a harness-maker in the Finger Lakes region of New York State, Curtiss grew up on a pile of metal parts, in an atmosphere of, “If we don’t have it, we can make it.” He left school at age 14.

The safety bicycle craze peaked when he was a teenager-liking speed, he became a bicycle racer.

Then, he became a bicycle dealer, with shops in three towns in his area. Ultimately, because no one else offered what he wanted, he began manufacturing bicycles under the Hercules brand name.

Curtiss had been a little late for the bicycle wave. He wouldn’t be late again. In 1900, he bought a set of castings to build a small engine to power a bicycle. To machine the parts, he employed Charlie Kirkham's shop in nearby Savona. Lacking a carburetor and ignition system, he made his own.

How does an uneducated person make carburetors and ignitions? With energy and imagination. In those days of invention, every library carried mechanics magazines such as the old Scientific American. Every new thing was written up and discussed in these magazines, and for those with more curiosity, there were industrial expositions, dominated by huge machines of the coming future.

He called his first motor-bicycle “The Happy Hooligan.” It carried him nine miles and ran out of gas. He wanted more power, because it was slow on hills. Curtiss quickly built a series of three bigger engines, each designed to correct the shortcomings of the one before it. Today, we call this “R&D.” By early 1902, he’d decided to be a motorcycle manufacturer. Expecting that winning races would bring many orders, he became a motorcycle racer. It worked.

When he needed more power, he added a second cylinder. This wasn’t the first VTwin in the world; others had been built in Europe, but that didn’t matter. Power was the thing-he could get all he wanted by just adding more cylinders.

On the eve of an important race, he still faced cutting-out from unequal distribution of mixture to the two cylinders (he would later solve this very directly by using one carb for each cylinder). To get the job done with what he had, he leaned out the rich cylinder by drilling a small hole in its intake pipe. This allowed his engine to show its full power. In 1904, he went 67 mph on a Twin at Ormond Beach, Florida. The next year, he ran a 1 -mile flat-track at Syracuse in 1 minute, 1 second.

Like other early engines, his had atmospheric inlet valves, pulled open against a light spring by intake vacuum. Exhausts had to be cam-operated. Curtiss added a ring of holes, drilled through the cylinder just above the piston at BDC. These, adjusted by a perforated ring, assisted breathing and relieved the hard-worked exhaust valve. Heat-resisting steel was yet to come.

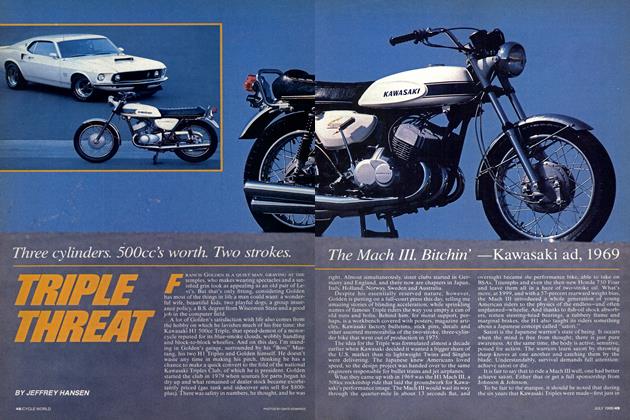

By 1907, the G.H. Curtiss Mfg. Co. produced 500 motorcycles a year-basic Singles and Twins. Not enough power yet? In 1909, he added a third cylinder to make a W-Three.

By 1904, his fame had reached the West Coast, and the ears of exhibition balloonist/parachutist Thomas Baldwin. Would Curtiss build Baldwin a special V-Twin engine to power a dirigible? This led to new directions, and eventually to a War Department order for a more powerful airship engine with two-hour endurance. Out of this work would come the V-Eight record bike.

As Charlie Kirkham recuperated from near-fatal diphtheria, he completed a correspondence course in mechanical engineering. Kirkham and Curtiss became design partners, two sides of a creative argument about everything-cooling, vibration, bearing design, manufacturing. After quitting twice, Kirkham went on to his own successes.

The 40-horsepower V-Eight motorcycle was a tough act to follow (it took the others until 1930, remember), and Curtiss wasn’t interested in refinements. On to the next problem and the next opportunity.

Alexander Graham Bell saw the Curtiss booth at a late-

1906 New York City Expo, and requested engines for airplanes he wanted to build. The Wright Brothers had flown at Kitty Hawk in 1903, but hadn’t publicized their work until 1908. Bell, Curtiss and others formed the Aerial Experiment Association and built airplanes powered by Curtiss engines. Curtiss taught himself to fly in his own design, the “June Bug,” in July, 1908. His wind tunnel used an auto radiator as a flow-straightener, and cigar smoke for flow visualization. He was the only member of the group without a university education.

In 1911, a Frenchman flew a floatplane off the Mediterranean. Curtiss had a better idea: the flying boat. Perfecting it required important advances in hull design, but for Curtiss, important advances had become routine.

The bike business languished. Curtiss had a new wave to ride: aviation. What followed would have killed lesser men. Flying exhibitions, contests, records, running a barnstorming service, building airship engines for the Army and seaplanes for the Navy.

More engine power needed more cooling, more than simple fins and air could provide.

“It’s the best engine in the world,” said Curtiss of his aircooled V-Eight, “for exactly three minutes.”

So he adopted liquid-cooling, with cylinders water-jacketed with brazed copper or Monel, a nickel-copper alloy. Overhead valves, all cam-driven, replaced restrictive atmospheric inlets and side exhausts.

When WWI began, the British government needed patrol aircraft to counter German subs. With crazy speed, the little, informal Curtiss operation in Hammondsport, New York, ballooned into a huge, multi-million dollar business, producing thousands of flying boats. Ever hear of the Jenny? That training airplane-favorite of bamstormers-was the Curtiss JN-4D. Its engine, the 503-cubic-inch Curtiss OX-5, was made by the thousands. One even powered a racing car built by Soichiro Honda in the 1930s.

While creating the aviation industry, Curtiss also had to deal with cheating partners and a bitter lawsuit brought by the Wrights, claiming Curtiss’s moveable aileron copied their lateral control system, wing-warping. Curtiss bobbed and weaved, created new corporations, kept all the balls in the air-while continuing his work.

It almost killed him, but he had the sense to stop. Soon after WWI, he moved to Florida and did business by telephone. He divided his last decade between hunting and flshing-and his fourth and last career wave, real estate.

And now a footnote to history, courtesy of self-educated engineers: Curtiss and Charlie Kirkham had often discussed the problem of engine flexure; its solution would allow engine speed and cylinder pressure to rise to new heights. Rigidity meant casting cylinders and crankcase in one piece. In 1916, they tested the resulting four-valve, 1145-cubic-inch K-12. It was happy at 2500 rpm, a big jump. The concept was proven.

That led to the later D-12, which won the two Schneider Trophy air races for the U.S. The British Air Ministry bought several, to stimulate thinking at English engine manufacturers. Rolls-Royce disapproved of the aero-engine business, but their eventual response was the great Merlin V-12, the engine that won the Battle of Britain.

Messing with motorcycles can lead almost anywhere.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontLetter of the Month

April 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe Mouse That Roared

April 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCThe Rpm Chronicles

April 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

April 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupNew Bmw Über-Tourer Twin

April 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupUltimate Towing Machine?

April 2002 By David Edwards