Apollo

Was Ducati’s 1963 l00-horsepower V-Four the world’s first power-cruiser?

IAN FALLOON

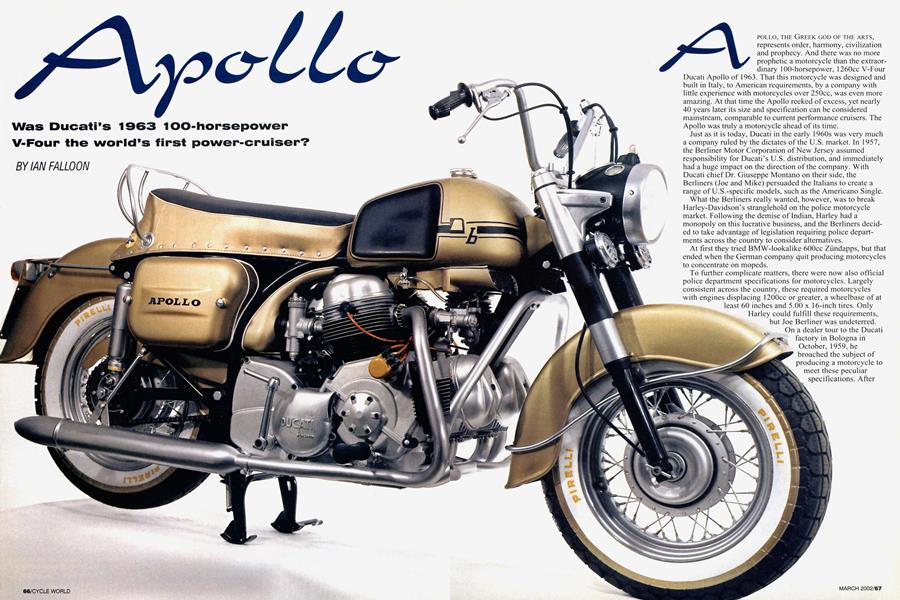

APOLLO, THE GREEK GOD OF THE ARTS, represents order, harmony, civilization and prophecy. And there was no more prophetic a motorcycle than the extraordinary 100-horsepower, 1260cc V-Four Ducati Apollo of 1963. That this motorcycle was designed and built in Italy, to American requirements, by a company with little experience with motorcycles over 250cc, was even more amazing. At that time the Apollo reeked of excess, yet nearly 40 years later its size and specification can be considered mainstream, comparable to current performance cruisers. The Apollo was truly a motorcycle ahead of its time.

Just as it is today, Ducati in the early 1960s was very much a company ruled by the dictates of the U.S. market. In 1957, the Berliner Motor Corporation of New Jersey assumed responsibility for Ducati’s U.S. distribution, and immediately had a huge impact on the direction of the company. With Ducati chief Dr. Giuseppe Montano on their side, the Berliners (Joe and Mike) persuaded the Italians to create a range of U.S.-specific models, such as the Americano Single.

What the Berliners really wanted, however, was to break Harley-Davidson’s stranglehold on the police motorcycle market. Following the demise of Indian, Harley had a monopoly on this lucrative business, and the Berliners decided to take advantage of legislation requiring police departments across the country to consider alternatives.

At first they tried BMW-lookalike 600cc Zündapps, but that ended when the German company quit producing motorcycles to concentrate on mopeds.

To further complicate matters, there were now also official police department specifications for motorcycles. Largely consistent across the country, these required motorcycles with engines displacing 1200cc or greater, a wheelbase of at least 60 inches and 5.00 x 16-inch tires. Only Harley could fulfill these requirements, but Joe Berliner was undeterred.

On a dealer tour to the Ducati factory in Bologna in October, 1959, he broached the subject of producing a motorcycle to meet these peculiar specifications. After considering the ancient sidevalve 1340cc Harley design, both Montano and Ducati’s chief engineer, Fabio Taglioni, believed they could create a more modern and cost-efficient design, even with the hefty import duties imposed at the time.

Taglioni, for his part, was eager to become involved in the project.

At that stage, he was still engaged in designing high-revving, desmodromic-valve, twin-cylinder racers, so the prospect of a Harleylike machine was a new challenge.

Unfortunately for both Montano and Taglioni, Berliner’s proposal came at a time of serious downturn in the Italian motorcycle market.

Ducati was only surviving because the bureaucrats in Rome were prepared to underwrite annual losses of the heavily state-subsidized company. There was no interest in funding what was felt to be a somewhat dubious project, and negotiations stalled.

In the meantime, Berliner acquired the U.S. distribution of Norton and Matchless, and approached their parent company, AMC, regarding possible construction of a police bike. If anything typified the reason for the failure of the British motorcycle industry, it was AMC’s answer to Berliner’s request. Yes, they would build a copbike, but only a parallel-Twin, and only a maximum of 800cc to keep vibration to an acceptable level.

Berliner had to go with Ducati.

Talks dragged on, but finally a deal was struck in 1961. A prototype and two engines would be built, but only after Berliner agreed to finance the cost of the prototype. Berliner also agreed to assist in the cost of tooling for production, and in return was allowed to dictate the specifications.

The project would be a joint venture between Berliner and Ducati, and would be known as the D/B-V/4. As to the specifications, Joe Berliner was quite specific: He wanted a

lightweight, I200cc, V-Four, shaftdrive motorcycle that would outper-

form the Harley in every respect. Ease of maintenance was also a priority, and this called for a simple design. A V-Four was no problem for Taglioni: Always a proponent of the concept, Taglioni even laid out a 250cc VFour many years earlier while studying at university. To meet the goal of simplicity, Taglioni agreed to build a pushrod-and-rocker overhead-valve design with a gear-driven single camshaft positioned in the engine’s vee, just like an American V-Eight.

In many other respects, however, the Apollo was surprisingly radical, with something of a performance emphasis. Dramatically oversquare even by today’s standards, the bore and stroke of 84.5 x 56.0mm resulted in I257cc. The all-alloy engine was extremely compact, effectively two 90-degree V-Twins laid side-by-side with individual finning for each cylinder. Power was transmitted through a gear primary drive, seven-plate wet clutch and five-speed transmission. Interestingly, the transmission case

was designed to accept the internals of a Sachs variablespeed automatic, as later used by Moto Guzzi in its unsuccessful lOOOcc I-Convert.

Although Berliner wanted shaft drive, Taglioni mistrusted such a design, and argued that it would also increase tooling costs. Thus a 3/8-inch duplex drive chain was fitted. A big battery and stout electrical system from a Fiat 1100 car were fitted, both to power the police paraphernalia of lights, radios and sirens, and also because the bike had electric starting to go along with its kickstart lever.

With a 10:1 compression ratio and four 32mm Dell’Orto SSI remotefloat-bowl, racing-style carburetors, the Apollo made 100 horsepower at 7000 rpm (redline was 8000). In 1962, this was almost outrageous power production, so a detuned, 80-bhp touring version was to be offered as an option.

In true Ducati fashion, the engine was incorporated into the frame as a stressed member. Certainly the structure was admirably strong, but it was necessary to detach the front cylinders to remove the engine from the frame. Completing the chassis specification was a specially constructed Ceriani 38mm fork, twin Ceriani shocks and the necessary 16-inch wheels shod with fat Pirelli tires. The wheelbase was a moderate 61 inches, just meeting the police specification. Dry weight was about 530 pounds. This made it much lighter than the big Harley, and considerably lighter than comparable machines manufactured decades later.

In an era where Harley had only recently discovered rear suspension, the Apollo's credentials looked impressive, at least on paper. Unfortunately, where the Apollo missed the mark was in the Italian interpretation of an American motorcycle. Just like with the Americano, Ducati decided a Wild West look was appropriate. There was a huge saddle with chrome grabrail, pullback handlebars and deeply valanced fenders. The original example also featured a tiny fuel tank that looked as if it was hijacked from the 175cc production line.

By the end of 1963, the prototype was completed, and initial testing confirmed it was adequately powerful and satisfied the design criteria. After an official ceremony in Bologna in early 1964, the machine was shipped to Berliner in Hasbrouck Heights. By now it had whitewall tires, a revised fuel tank and was painted metallic gold. Berliner was so confident in the success of the Apollo that he had sales literature printed and released in March, 1964. Here, it stated that manufacture of the Apollo would commence in early 1965 for foreign markets, with shipments to the U.S. scheduled for the second half of the year. The projected price was $1500.

Basically, the Apollo was ready for production, but this was where the project came unstuck. As soon as the bike was

uncrated and run on the road, the rear tire noticeably expanded under power, eventually separating from the rim and tearing the valve stem out of the inner tube. Although the Apollo was a won-

derfully stable and comfortable highway machine, period tires couldn’t cope with sustained 100-mph operation, and no tire manufacturer was prepared to construct suitable rubber.

The solution was to reduce the compression ratio to 7:1 and fit milder cams, dropping power to a much less inspiring 67 bhp. This still ensured higher performance than the Harley, but restricted top speed to around 100 mph. The detuned Apollo may have been adequate to gain police contracts, but its power-to-weight ratio was now' markedly inferior to both the BMW and British Twins.

Undeterred, Berliner demonstrated the prototype to select police departments, but political events in Italy soon sabotaged the project. At that time, Ducati's hometown of Bologna was the center of pow;er for the Italian Communist Party, which was continually at loggerheads with the ruling center-right coalition of the Christian Democrats. Although the bureaucrats in Rome cited the tire problems and a reduced market for a detuned Apollo, there was no doubt that political loyalties influenced their decision not to provide any more funds for the project. They even refused Berliner's assistance. But he always remained hopeful; right through the early 1970s, Berliner believed that production of the Apollo would eventuate. He kept the prototype, even fitting a 750 GT instrument panel, gas tank and seat in 1972. Taglioni, too, always had a fondness for the V-Four, the second engine remaining on display in his office until his retirement.

As the largest capacity motorcycle to come from a European manufacturer since World War II, the Apollo suffered from being too far ahead of its time. The idea of a 530pound, 100-horsepower V-Four was just too radical for the early 1960s. Fortunately, Taglioni wasn’t discouraged by its failure, and was able to use many of its features as an inspiration for his 750cc V-Twin seven years later. Because of the success of the 750, Ducati and the 90-dcgrce V-Twin have since become synonymous. But imagine how history might have changed if the Apollo had been successful.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontCollecting Made Easy

March 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsThe 11th-Hour St1100

March 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCKnock, Knock...

March 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

March 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupMotogp's Newest Recruits

March 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupHonest Injun?

March 2002 By David Edwards