LeGrand Jordan and the Impossible Dream

CYCLE WORLD 19622002Z retrospective

Seventy years ago, a motor officer decided he could build a better bike, and that people would want it. He did. They didn't.

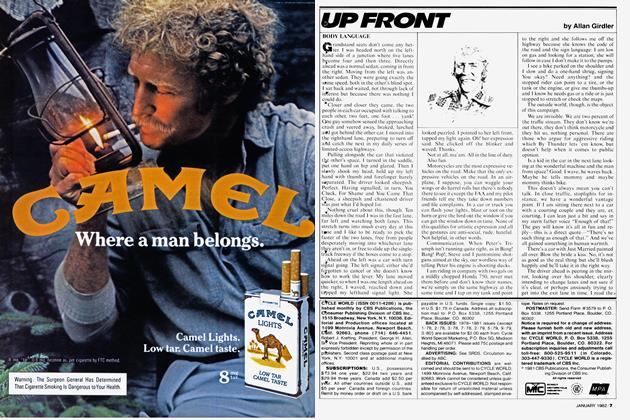

ALLAN GIRDLER

"GENTLEMAN," A TERM BOTH USED AND ABUSED, IS A perfect fit on LeGrand Jordan. He's 82, a retired motorcycle patrolman, still straight as an arrow. Quoting scripture, his eye is not dimmed nor his nat-ural force abated.

When Jordan joined the California Highway Patrol in 1930, he liked the job. What he didn't ____________

like was the standard-issue motorcycle. His CHP Harley 74 seemed too big, too troublesome, and Jordan never has fig ured why cars graduated from chain to shaft drive and motorcycles didn't.

One day in 1932, Jordan was thumb ing through an English motorcycle magazine and came across an article on the Ariel Square 4. Of course, he said to himself. That's the perfect engine for a motorcycle.

So, he set out to build one. Not an Ariel copy, but his own design. Jordan was not an engineer, but he was mechanically inclined, as all bikers

needed to be in those days, and he knew lots of trained peo ple who were willing to help.

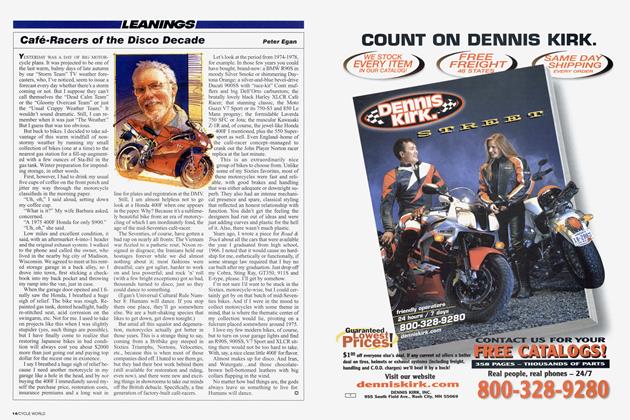

The engine is so different and so sensible that it takes some effort to explain. It's a square-Four, air-cooled. The crankcase is one piece, including the four barrels. One piece means one piece, in that the crankshafts are inserted into the case through access plates and the case itself doesn't split. The two crankshafts are aligned with the wheelbase, that is, side by side, fore and aft. They are geared together and rotate in opposite directions.

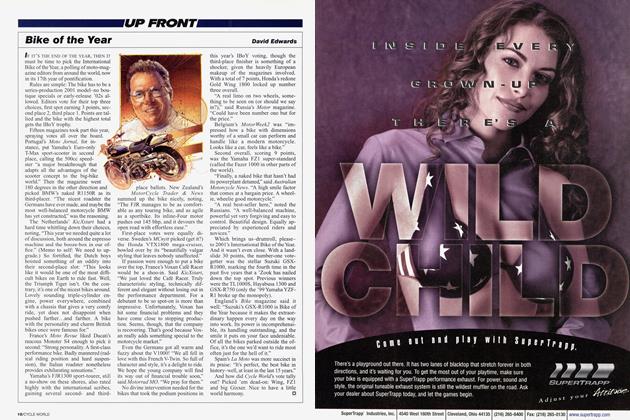

---ditor's Note: For every Erik Bueli, for every Firebolt XB9R, there are a hundred designers with a hundred Innovative machines that don't make ft. Count LeOrand Jordan and his all-enclosed Jordan Four among those. But, boy, he came close. To say his prototype, built in the 1930s, was ahead of its time, is an epic under statement. Engine, suspension, brakes and bodywork all showed the touch of brilliance. This story, originally published In the October, 1983, issue is reprinted here In largely unedited form.

Here begins the tricky part. Each crank is a 180-degree, one throw up when the other is down. The cranks are half a turn apart. Thus, when the left front piston is at TDC, the right front is at BDC, the right rear is at TDC and the left rear is at BDC.

The first benefit from this is that two slugs are going up while two are going down. Two stop at the top when two stop at the bottom, i.e., nearly perfect primary balance. The counter-rotating cranks effectively cancel the torsional reaction of, say, the longitudinal BMW Twin, although the Jordan’s four-speed transmission, running off the rightside crank, would produce some torsion force.

But, considered against the engines of the early Thirties, or even later, the Jordan’s balance is incredible.

There’s more. Picture the pistons as being in an “X” config-

uration, viewed from the top. The left front piston comes up, then the right front, the right rear, then the left rear. Yes, we have here a rotational firing order. It runs clockwise : around the center of the X.

What's in the center of the X? The camshaft. With two lobes. It's vertical, aligned

with the bore centers and driven by a bevel gear off the righthand crank. It runs at half the crank’s speed. Atop the camshaft is the distributor.

The cylinder head, one piece, is super-radial. Exhaust ports are at the tips of the X, intake ports directly inboard. Two valves per cylinder, hemispherical combustion chambers, domed piston crowns. Rocker arms on shafts sit in housings above each cylinder. Horizontal pushrods, one for each valve, run from cam followers, also horizontal, that radiate from the central camshaft.

How neat, how easy, once somebody figures it out for us, which is just what Jordan did.

Jordan wasn’t too far ahead of his time, so there’s a foot clutch and hand shift, the latter on the handlebar. Final drive is shaft, which even 50 years ago looked like a good idea.

Jordan’s frame may be too practical. It’s pressed steel.

Tube frames have been used since Day One, probably because the first motorcycles were bicycles with engines. Tube frames are expensive. Jordan had been to the Harley plant and seen sections of tubing measured, cut, trimmed and bent, then put into jigs while the lugs, brackets, etc. were added. He figured a pressed-steel frame could be just as strong, at one-fifth the cost, so that’s what he used.

Suspension. The Jordan has suspension front and back, which alone would make it different. Several makers tried rear suspension in the Teens, but by 1932 only Vincent and a few of the other English bikes, even less well known, weren’t rigid.

His daily duties, at speed on bad roads with the rigid police bikes of the day, made Jordan a believer. So his design not only had suspension, it had the latest kind. The name was “Torsilastic,” and let’s hope the musty old books in the library had the spelling right. It’s different, thus difficult to properly describe.

The rear wheel is attached to the trailing arms of a swingarm, like those we have today. At the pivot end, though, there are two steel cylinders, one inside the other. Between the tubes, and bonded to each, is a long rubber doughnut. One cylinder is clamped to the frame, the other to the swingarm and the doughnut flexing between them provides both springing and damping.

The front suspension is the same, in reverse. There’s a steering head and stem, and stanchion tubes, just like now except the tubes are solidly mounted and run straight down to about the top of the tire, then angle back until they’re directly behind the front hub. Between the tubes and the hub is another swingarm, leading instead of trailing. The Torsilastic doughnut bonded to the inner and outer cylinders attached to the stanchion tubes and the swingarm is the same, except smaller, as in the rear. Wheel travel is about 3 inches, not enough today, but radical back then.

Brakes are the best of their time, aircraft. Another distinct difference here. There’s a center drum, around which goes a bladder, sort of like a very small, very thick inner tube. Outboard of this bladder, pivoted from a backing plate, are segmented brake shoes, seven in all. Outboard of them is the actual brake drum. When the brake is applied, hydraulic fluid expands the bladder, which moves the shoes against the drum. Lots of little shoes make closer, more complete contact with the drum and thus use all of the drum’s surface, which the two shoes of conventional drum brakes never quite do. Disc brakes work better still, but they didn’t come until airplanes got heavier and faster in the late 1940s.

The Jordan’s styling doesn’t need to be described, but it does deserve an explanation.

This (obviously) is an enclosed motorcycle. For 70 years people have been enclosing bikes to protect the rider from grit, mud, water and wind, and for 70 years other people have been refusing to buy the idea.

But in the past, enclosed motorcycles were the coming thing, so Jordan used a full body, done by his brother. It looks unusual today, but that’s because style

changes. At the time, the Art Deco look was how artists did it and the Jordan looks like something that would have resulted if the stylists who did, say, the Indian Chief had gotten together with the stylists for the enclosed Vincent Black Prince. It also bears an uncanny resemblance to the more recent motorcycle projects done by Porsche Design, but that’s probably more a comment on Porsche Design than on the Jordan.

Style aside, the Jordan’s body does useful things. Internal panniers, accessed via hinged doors, provide storage. The two-person seat swings up for access to the air cleaner, distributor and batteries. There were two of the latter because the electric start-

ing didn’t work as well as the outside expert engineer said it would. Jordan was firm on the need for electric starting; no man who’s executed 53 kicks without getting an engine to run ever feels quite the same about the purity and efficiency of the kick-start motorcycle.

The prototype weighs-note the present tense^450 pounds. The engine displaces lOOOcc, or 61 cubic inches, as they said then. There was no emphasis on power, so “adequate,” as Rolls Royce puts it, is the only rating. Jordan applied for, and was granted, several patents on the drivetrain and valve system.

Now, if there is a moral to all this, it must be that what seems to be the hard part, wasn’t. Any bike nut who’s ever done any maintenance knows he couldn’t come close to designing and building his own motorcycle, never mind one that incorporated things production bikes of the day didn’t have.

But here was LeGrand Jordan, a highway patrolman, no credentials, no investment capital, nothing but faith and energy, and he did it.

That was the easy part.

The hard part was money. There was no way Jordan could manufacture his motorcycle himself, nor-this being the Depression-was there any hope he could raise the money himself. He needed to find a motorcycle company that would use his design, or some related company that wanted to be in the motorcycle business.

Jordan knew a member of Harley’s board of directors, a man who was frank enough to say, sure, there were lots of things wrong with Harleys. The factory knew what they were, but they didn’t plan to fix them, or to build newer and better machines, because they already dominated the market.

Indian? By this time, Indian was in financial trouble, and they already had a Four, albeit an inline that was out of date. Jordan wrote them some letters, never got a reply and wasn’t terribly surprised.

Armed with patents and plans and belief in his ideas, Jordan criss-crossed the country on his BMW. He visited car companies, steel companies, any firm with manufacturing capabilities and the remotest link to wheeled vehicles.

“Some could say no in a few pages, and some could say no in two lines, but they all said no,” recalls Jordan.

The approach of World War II gave renewed hope, and put the Jordan Four as close as it’s come to production.

Studebaker had been near collapse until the arrival of Paul Hoffman, who would later do great things for the war effort. Hoffman broadened and diversified Studebaker’s product line and he knew the military had interest in motorcycles.

Jordan wrote to Studebaker, and Hoffman sent a cordial reply. Jordan went for a visit, the men talked for most of the day, and at the end of the session, plans and drawings had been assigned to the Studebaker engineering staff. That was in July, 1941. Before anything got off the drawing board, it was December, 1941. There was no time to experiment. The military contracts went to established factories. Studebaker did other war work, then

ventured into different areas after the war, producing compact cars and finally the semi-custom Avanti, which Jordan believes was a substitute for going into the motorcycle business. “If they’d built the Jordan instead of the Avanti, they’d be the leader today,” he says.

Arguable, but understandable under the circumstances. We are compressing decades into a few words,now, but Jordan bought a secondhand school bus and toured, with his bike in the back, displaying and demonstrating to anybody who might be willing to make motorcycles.

Nobody was. Then Honda and the others arrived, and created a market far bigger than anybody dreamed. In time and in turn, Jordan approached them all.

And got nowhere, for valid reasons. The Japanese didn’t invent Not Invented Here, but they practice it; companies with hundreds of engineers on the payroll don’t enjoy paying for ideas from outside. Nor can any large corporation forget that scores of lawsuits claiming infringement and/or theft are filed every year.

There the matter rests. Jordan maintains an active correspondence file, packed with letters from engineers endorsing his ideas. He describes his project in the present tense, as in the changes that would have to be made if production began tomorrow. In the next sentence, though, he’ll say that he took the engine from its display bench and put it back in the chassis because he won’t be here forever, and he’d like to see the bike go to a museum, so he’s made it easy for the museum staff to know where everything goes.

Speaking realistically, the Jordan Four isn’t going to be produced. Progress has caught up with the radical suspension and brakes and bodywork. The engine’s concept is still interesting, and probably workable-water-cooling could be added easily-but the world surely has all the Fours it needs.

Speaking emotionally, it’s worth noting that Jordan is not a bitter man. He has a devoted wife, children and grandchildren. He grows fruit trees in his backyard, rides and tinkers with his BMW. LeGrand Jordan worked for 50 years on his better motorcycle, but he never let it interfere with his life.

He told his story with some reluctance. Just as the manufacturers didn’t want to know, so are there people who will borrow the work of others. Jordan is willing to show the bike now, he says, because, “It doesn’t matter to me.”

But of course it really does.