Clipboard

Is Hayden last true AMA Superbike champ?

Even though Honda’s Nicky Hayden led the AMA Superbike Championship from the time he won the Daytona 200 until he clinched the title in Virginia five months and nine race wins later, he never had a moment’s rest.

He can thank Kawasaki’s Eric Bostrom, who won four races himself, and only really lost his chance at winning the title when his engine locked-up and caused his race-one crash at VIR.

This epic, season-long battle between Hayden’s lOOOcc V-Twin and Bostrom’s 750cc inline-Four underlines how different the AMA series is from World Superbike, yet both are contemplating similar changes in technical rules. World Superbike has become a Battle of the Twins in which only Ducati, Honda and Aprilia are competitive, while the 750cc Fours of Suzuki and Kawasaki are also-rans. Contrast that with AMA-Honda’s RC51 Twin has finally won a title, but only after three years of

domination by Mat Mladin’s “obsolete” Suzuki GSX-R750. While the Suzuki has been slowed this season by handling ills, the action has come from Bostrom’s reborn ZX-7RR-another bike that’s not

supposed to be this fast. The highestplaced Ducati in this year’s AMA chase was Pascal Picotte’s privateer 998, fourth in the final standings.

Despite the differences in the two series, both WSB and AMA plan to add lOOOcc Fours to the starting grid. The FIM proposes to allow full modifications to Twins an2d Fours alike, then to “adjust” four-cylinder competitiveness by placing intake restrictors in airbox snorkels. The AMA-always favoring a cost-controlling outlook-prefers to limit big Four horsepower by allowing only Supersport-type mods.

Why fix what ain’t broke? Both series provide close, exciting racing. Published reasons for change are “letting the factories race what they sell” (the popular liter-class Fours), and doing something to boost entries. Could the FIM and AMA know something about factory plans that the rest of us don’t?

Existing lOOOcc classes such as Formula Xtreme have privateer appeal because it’s so much easier to make competitive power when you start with a big engine. In the U.S., homebuilt Superbikes are a vanished species-privateers just ride their Superstock 750s on slick tires.

Problems? First, the FIM’s restrictor scheme is untested and is expected to create enforcement difficulties-such as “accidental” air leakage past cable, wires and hoses that must enter the airbox. In the U.S., highly modified FX bikes typically lap 1.5-2.0 seconds slower than 750cc Superbikes. Supersport engine limits can only make them slower yet.

Aprilia racing boss Jan Witteveen came to the Laguna Seca World Superbike weekend to urge AMA Competition Manager Merrill Vanderslice to bring AMA rules close enough to WSB to make two different bikes and development programs unnecessary. Vanderslice explained that while the FIM can expect manufacturers to produce bikes to suit its rules, the AMA must tailor its classes to what exists-and must consider privateers.

What next? The FIM and AMA will feel their ways forward, making up rules as they go. Trial and error is the only proven way to create an equitable racing class for different engine types. Does this mean the fast may sometimes be punished and the slow (including sandbaggers) rewarded? Yes, but we hope this will be limited to a start-up period, after which adjustments will be few and racing will be real.

-Kevin Cameron

Edwards tops third Suzuka 8 Hours

There are a number of reasons you wouldn’t want to do the Suzuka 8 Hours, the most obvious being the heat. Famous for ridiculous conditions, this year was no different-a steady 95 degrees and 70 percent humidity greeted the 66 starters. That adds up to a normal, healthy person becoming dehydrated after a lengthy brisk walk, never mind wrestling with a Superbike an hour at a time four times during the race, while wearing full leathers.

But there is also the chasm between the speed of the factory Hondas-three swept the podium this year-and the rest of the field. For Honda’s top guys, such as the winning duo of Texan Colin Edwards and his teammate Daijiro Kato, it is forever a dangerous battle of slicing through much slower lapped traffic.

As a result, most of the big names in Grand Prix and World Superbike give it a miss. And even Edwards might not have been there to take his third win if Tohru Ukawa hadn’t been injured and needed replacement.

For the mostly Japanese factory riders who did come, it was clear the deck was stacked in Flonda’s favor. The official Suzuki team of Akira Ryo and Yukio Kagayama seemed like they had a chance to at least make the podium, but when their GSX-R750’s engine let go with only an hour or so to the finish, the strain that had been on the equipment became apparent. The factory Yamahas made a good show in fourth and fifth, but were simply outpaced by the incredibly fast Hondas. There was no factory Kawasaki effort, Team Green apparently allocating the bulk of its racing budget to the MotoGP ZX-RR project.

The third tier, behind the Hondas, behind the other factory teams, was the race for the World Endurance Championship. Series regulars Team Zongshen (a Chinese motorcycle manufacturer running a pair of GSX-R 1000s) finished nine laps down in seventh and eighth, then clinched the championship at the next round in Oschersleben, Germany. Also of note was the surprising holeshot from 13th on the grid by twotime World Superbike champ Doug Polen. His CBR954RR was quickly swallowed up by the factory teams, then later ran out of gas.

But as the 8 Hours celebrated its 25th year, it was clear something was missing, the party not quite the same. Oncemassive crowds have dwindled in recent years, and while Honda put on the big show as usual, the epic glory of this great race has somehow faded. Perhaps the crowds will only come if the GP and WSB stars are going to be there in force. Without them, the Suzuka 8 Hours may just become another world endurance race, not the great showdown it once was. -Mark Wernham

Randy Renfrow, determined ’til the end

In one of the saddest ironies in American roadracing history, Randy Renfrow, the veteran racer who so often battled back from serious injury, has died in a household accident.

Still recovering from the multiple broken bones he sustained at Daytona this past March, the 46-year-old fell down a flight of stairs at his parents’ house in Virginia on August 6th, hit his head and lapsed into a coma. Doctors performed surgery to relieve pressure on his brain, but when he showed no signs of improvement after three days, his family made the difficult decision to remove him from life support. He was buried in a set of Camel Honda leathers and a Dunlop cap, following a large funeral attended by many of his friends from the racing community.

I was naked when I met Randy Renfrow in the summer of 1988, which was okay, because he was naked, too. And if he hadn’t been then, he definitely had been earlier, when he and a certain representative from a certain tire manufacturer “streaked” through the bar at Siebken’s in what had become an annual tradition.

Used to be there were three national roadrace weekends in a row, last of which was at Road America in Elkhart Lake, Wisconsin, and when it was all over, the racers liked to blow off a little steam. When the bar shut down, the party adjourned to the beach across the street. I stripped and jumped into the lake to avoid having a certain skyscraper of a tuner throw me in fully clothed, and when I emerged, Renfrow and two attractive California girls were sitting on the picnic bench where Ed left my clothes. I ended up dating one of the girls, whose formal name was Kathryn, which prompted Randy to joke, “You know, you two shouldn’t get serious, because if you got married, she’d be Kitty Catterson.”

Renfrow was a serious racer, but he was a fun guy, too. As a Cycle News cub reporter, I learned to appreciate his candor; if he’d ridden poorly or had a mechanical problem, he told you so, without any of that infuriating, mousein-the-pocket “we” stuff they teach at NASCAR finishing school.

A diminutive person at 5-foot, 4inches and 120 pounds, Renfrow excelled on purebred two-stroke racing machines, winning the 1983 Formula 2 (now 250cc Grand Prix) and 1986 Formula 1 Championships. But he was accomplished on the big four-strokes as well, winning the 1989 Pro Twins GP1 title on a Ray Plumb special powered by a Honda RS750 dirt-track engine, and finishing second in the 1990 Superbike standings after winning the season finale at Willow Springs on a Camel Honda RC30.

For all of his achievements on the racetrack, Renfrew will unfortunately be remembered for being accidentprone. He had a number of big crashes during his career, the most infamous of which occurred while he was testing the aforementioned RC30 at Willow Springs in 1991. He fell in super-fast Turn 8, got his hand caught beneath the bike and lost his right thumb and the tips of two fingers. Undeterred, he had surgery to graft his big toe in place of his thumb and returned to racing the next year in the 600cc Supersport ranks, finishing fourth in the series standings. The following year, he was third.

Renfrew had been seriously injured at Willow once before, during the annual 24-hour endurance race, and he earned a Life Flight helicopter ride to the hospital after he tangled with Roland Sands during a 250cc GP final at Sears Point a couple of years ago. Each time, he trained hard (he owned a fitness-equipment company by day) and returned to race again. And that’s what he was talking about after his final accident at Daytona.

Determined ’til the end-that was Randy Renfrew. Brian Catterson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Other Side of Speed

November 2002 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Morning In Italy

November 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCLiving In Harmony

November 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

November 2002 -

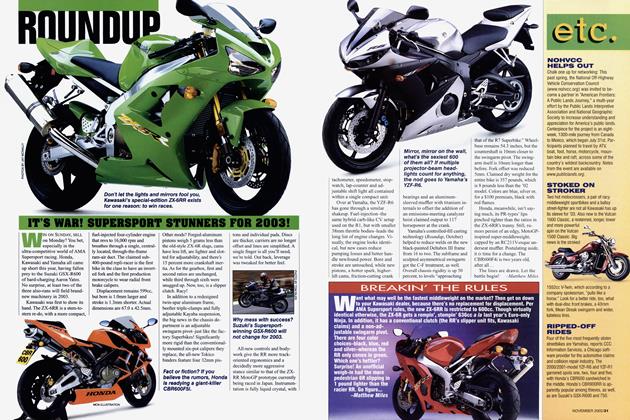

Roundup

RoundupIt's War! Supersport Stunners For 2003!

November 2002 By Matthew Miles -

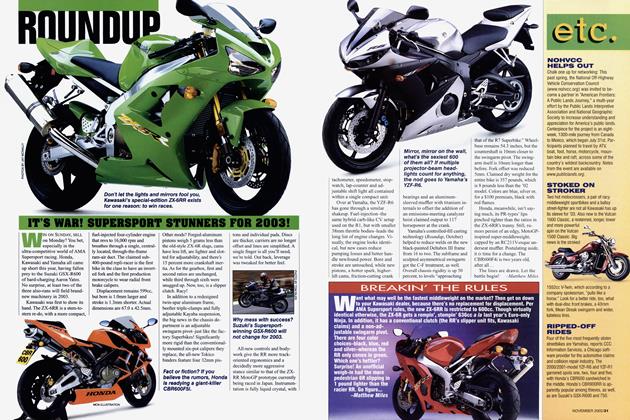

Roundup

RoundupBreakin' the Rules

November 2002 By Matthew Miles