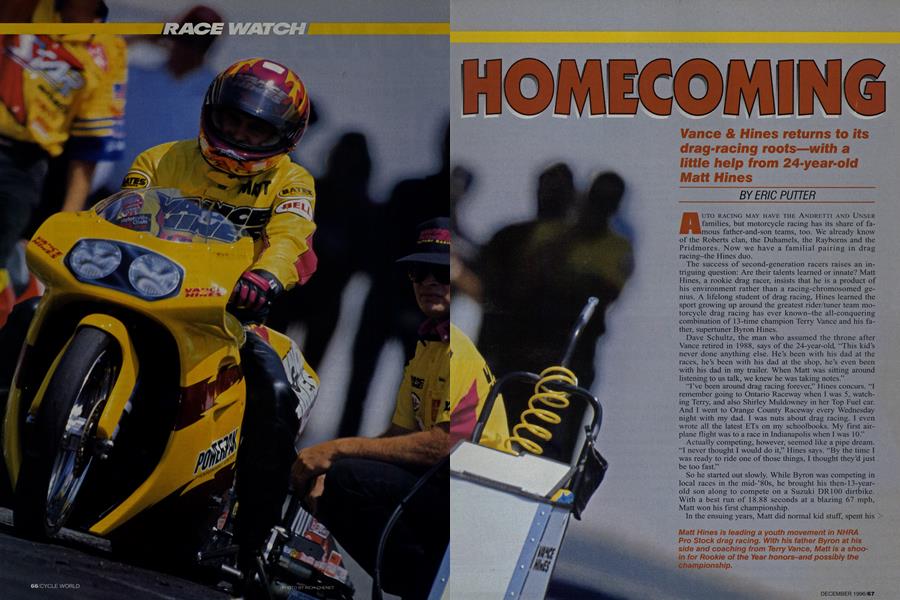

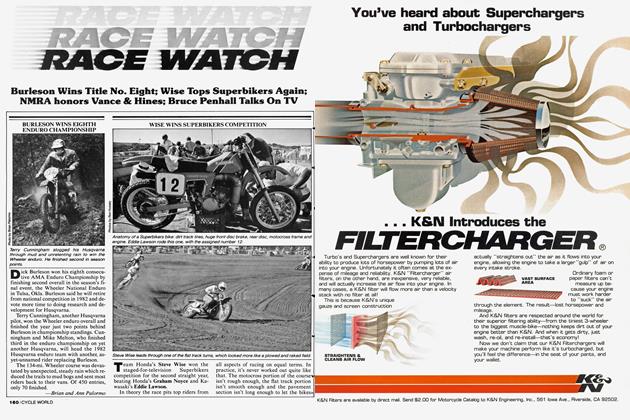

RACE WATCH

HOMECOMING

Vance & Hines returns to its drag-racing roots-with a little help from 24-year-old Matt Hines

ERIC PUTTER

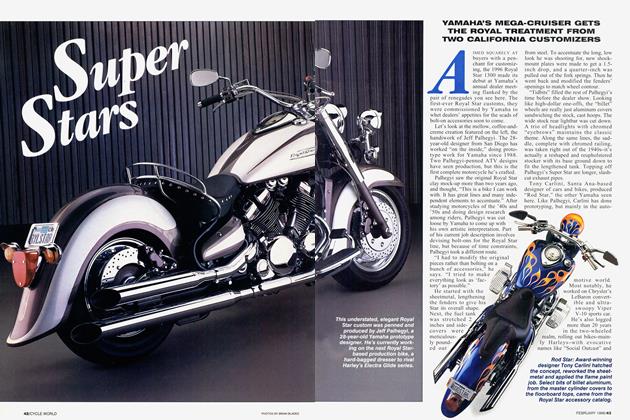

AUTO RACING MAY HAVE THE ANDRETTI AND UNSER families, but motorcycle racing has its share of famous father-and-son teams, too. We already know of the Roberts clan, the Duhamels, the Rayborns and the Pridmores. Now we have a familial pairing in drag racing-the Hines duo.

The success of second-generation racers raises an intriguing question: Are their talents learned or innate? Matt Hines, a rookie drag racer, insists that he is a product of his environment rather than a racing-chromosomed genius. A lifelong student of drag racing, Hines learned the sport growing up around the greatest rider/tuner team motorcycle drag racing has ever known-the all-conquering combination of 13-time champion Terry Vance and his father, supertuner Byron Hines.

Dave Schultz, the man who assumed the throne after Vance retired in 1988, says of the 24-year-old, “This kid’s never done anything else. He’s been with his dad at the races, he’s been with his dad at the shop, he’s even been with his dad in my trailer. When Matt was sitting around listening to us talk, we knew he was taking notes.”

“I’ve been around drag racing forever,” Hines concurs. “I remember going to Ontario Raceway when I was 5, watching Terry, and also Shirley Muldowney in her Top Fuel car. And I went to Orange County Raceway every Wednesday night with my dad. I was nuts about drag racing. I even wrote all the latest ETs on my schoolbooks. My first airplane flight was to a race in Indianapolis when I was 10.” Actually competing, however, seemed like a pipe dream.

“I never thought I would do it,” Hines says. “By the time I was ready to ride one of those things, I thought they’d just be too fast.”

So he started out slowly. While Byron was competing in local races in the mid-’80s, he brought his then-13-yearold son along to compete on a Suzuki DR 100 dirtbike. With a best run of 18.88 seconds at a blazing 67 mph, Matt won his first championship.

In the ensuing years, Matt did normal kid stuff, spent his summers working at Vance & Hines, the high-performance empire that Terry and Byron established, and even learned how to build motors in the shop on Saturdays. But he didn’t race again until 1991, this time on a Suzuki GS500. “The first run was like a blur,” he recalls. “The wind made it feel ungodly fast.” In actuality, he hardly broke into the triple digits, with a best run of 13.37 seconds at 100 mph.

During the next two seasons, things got more serious. When Byron decided to turn the tables and ride a Vance & Hines Pro Stock bike himself, Matt was a crew member. “I watched everybody’s runs and learned a lot,” he remembers.

This intense experience put the racing bug back in him, but it took almost three years for Matt to realize his dream. “The last thing Terry said to me before I went to the Frank Hawley Drag Racing School was, ‘Don’t try to be Dave Schultz out there,’ meaning don’t outdo yourself and get into trouble.”

He didn’t. “I couldn’t believe it,” Matt says of his experience at the Gainesville, Florida, drag school.

“After 30 minutes, they told us to get into our leathers. Within an hour, we were on the bikes. George Bryce, the on-track instructor, showed me how to sit on the bike and let the clutch out with my back angled forward, elbows bent a little bit, and all my weight thrown into my butt. He said, ‘Pop the clutch, don’t be afraid.’ I was terrified!

The thing was almost a full racer, just 20 horsepower shy of my current bike.” At first, the elder Hines didn’t relish the notion of having another racer in the family, but says, “He kept talking like he wanted to ride. Any kid would say that, so I took him down to the school to see if he was serious.”

Within a few heart-pounding, highdecibel rides, Matt went from lifetime insider to bonafide Pro Stock competitor. Of these trial runs, Bryce, a former Funnybike champion who owns drag racing’s number-two team, says, “The kid knew what to do before he ever did it. Matt was so smooth right off the bat.”

“I was pretty pumped and immediately addicted,” Matt admits. “Conquering the starting line wasn’t a big deal, but getting to the other end going over 150 mph sure was. I never thought I’d get used to the speed.” Byron says the decision to let Matt loose was an easy one. “He’d paid his dues and made drag racing a priority, so we gave him a shot. Instead of going out on Friday night with his friends, he’d stay at the shop with me and work on bikes. Once 1 saw that kind of commitment, it wasn’t too tough to take the next step.”

The next step was to leap back into the Pro Stock limelight with the National Hot Rod Association. But it had been eight years since the Vance/Hines duo quit drag racing, and Byron had to think hard about making the commitment. He says, “I was on the fence a bit about getting into this deal because I spent so many years on the road with Terry. It’s a major sacrifice.”

Once a plan was in place, a machine had to be readied. Instead of starting

fro m scratch, the team chose to go with tried-and-true technology, in the form of a Suzuki GSl 150-based motor-just like the one V&H used in the glory days. Byron explains: “I didn’t want to do a mega-development deal and try to go racing. The worst thing for Matt would have been to show up with a semicompetitive bike that broke all the

time. We wanted to start with equal equipment and evolve the program from there.”

These are words of experience. With his company under contract to Yamaha to field a roadrace team, Hines decided to build an FJl200-based dragbike for his own race effort in 1991 and ’92. This netted a bunch of heartache and just one main-event win.

“The Suzuki is like a small-block Chevy,” Byron says. “There’s lots of parts out there for it and we know what’s gonna work or break.” For the record, the 260-plus-horsepower motor uses a stout GS bottom end, 1500cc aftermarket cylinders and a head ported by the master himself. It breathes through QwikSilver carburetors, is normally aspirated and runs on race gas. The Track Dynamics frame and fork were bought used. As per the rules, the bike and rider weigh 600 pounds together.

The connection with Suzuki brings up many questions, the most obvious being Vance & Hines’ six-year tie to Yamaha. Vance explains the situation: “Our (roadracing) contract is up this year, just like it was three years ago. I don’t know what will happen with Yamaha; we’ll just have to wait and see. Our company doesn’t function on racing, it functions on production. If the contract doesn’t come through, it’s not the end of the world” (At presstime, Yamaha announced that it would not renew its contract with Vance & Hines, and is moving its roadracing effort in-house).

After twice attending the Hawley school and doing a few days of testing, Matt was confident about his rookie season debut. “I knew I’d have the horsepower to be right there,” he says. “We made over 30 practice runs at L.A. County Raceway, with a best of 7.90 seconds (Angelle Seeling holds the class record with a 7.37 run). We used the same setup in testing at Gainesville and did a 7.66. This made me realize I could do it.”

How could a rookie be so competitive right out of the gate? Bryce says new technology, especially adjustable multi-stage lockup clutches, makes the bikes easier to ride, but he doesn’t credit the machinery alone. “Matt is real fluid and never upsets the bike,” says the drag-racing professor. “He’s mentally modeled himself after the best in the world and eliminated the things people do wrong.”

Dave Schultz critiques the rookie’s riding and offers up his own theory. “Matt really clings to the bike because it’s a violent handful,” he says. “Terry and I started out on much slower bikes. We sat up straighter and hovered over the controls. The clutch was the critical part in making the bike work. We used to have to modulate the clutch; now you just go up there and explode. On today’s bikes, the power is meted out mechanically. This takes part of the job out of Matt’s hands and puts it in Byron’s.”

In addition to having the sport’s most respected tuner delivering the power, Vance has whispered in Matt’s ear as well-though not as loudly as you might think. “Terry is a good coach and acts as my own private cheering squad,” Matt says. “He just kinda watches me. From the beginning, he said my riding was perfect.

He hasn’t said much about technique. The main thing he does is keep me focused on racing and tells me how to forget about the guy in the next lane.”

So, does Vance miss riding Pro Stockers? “There was nothing more fun,” he says. “To be on the leading edge of something is great. Working hard in competition is always rewarding, but the political side of it was just horseshit. That’s why we got out. But now, I kinda have a renewed spirit. That’s what’s really nice about this deal with Matt. It’s done the same for just about everyone in the shop, especially the veterans. They remember the days when we were the kings.”

In his rookie season, Vance & Hines’ new lead rider quickly established himself among the front-runners. Matt made it to the semi-finals in his first four out of five appearances, gaining the respect of his peers.

In the sixth round, Matt finally made it through the semis, beating three-time NHRA Champion John Myers. This left him with only one roadblock-broad-shouldered Dave Shultz, the grizzled veteran, a man Matt has dubbed “The Intimidator.” “After beating Myers, I thought I could beat Dave,” Matt says. “He likes to stage last, but somehow, I made him stage first this time. We sat there for at least a minute. I didn’t look over at him once. He went in, I went in—and then he smoked me. Okay, so I choked.”

But Matt wasn’t too disappointed with his performance. “Most of the guys who go up against Dave choke,” he states.

It was at the next round, in the Hines family’s adopted hometown of Denver, where Shultz finally faltered— or as Bryce says, “let a competitor into his helmet.” The defending champion ran comfortably quicker than the field until Myers stole the track records in the semi-finals. Instead of keeping his eyes on the prize when going up against Hines in the main event, Schultz sought to gain back the records. The fatal error was a clutch adjustment for the final that caused his bike to leave in a lurch.

Hines, determined not to choke this time, launched perfectly. “I couldn’t believe it,” he says. “I went up there, popped the clutch, looked over and Dave was almost a bikelength back. I stayed tucked-in until the end. It was like a slow-motion dream, overwhelming. I was on top of the world.” Schultz graciously welcomed Matt to the big-time, but with fair warning: “Matt has won now, so he’s not a rookie. Now he’s a peer and deserves no special treatment.”

For Byron, this was more than a sweet victory. “It’s really neat to see all the other racers who were so skeptical come up to him now; that’s the biggest thing for me,” he says with more than a hint of fatherly pride. “I think they used to look at him as a spoiled kid-you know, Byron’s son and all that. He’s shown a lot more insight into drag racing than those guys ever imagined.” Astronaut Walter Schirra said the following of his own boy, who pursued his father’s profession: “You don’t raise heroes, you raise sons. And if you treat them like sons, they’ll turn out to be heroes, even if it’s just in your own eyes.”

For Byron Hines, seeing is believing. □