TDC

Liquid assets

Kevin Cameron

THE SHAPE OF A MOTORCYCLE’S FUEL tank is a major part of its appearance, but aesthetics aren’t the only force that molds its shape. The sensuous, curvaceous form of a Ducati 250 Diana tank, for example, was very appealing, and it fit the rider well, but the nature of the fuel system put the tank where it was, vehicle dynamics determined its length and metal-forming technology permitted its complex form.

On the very earliest motorcycles, the tank could be anywhere because evaporator carburetion systems were widely used. Intake air passed into the fuel tank, where it picked up fuel evaporating from multiple wicks or from a special apparatus heated by exhaust gas. With this system, the tank did not have to be above the carburetor because there was no carburetor and so no need for gravity feed. Accordingly, early tanks were often strapped to the front frame downtube.

Once the spray carburetor took over from these evaporators, the easiest way to meter fuel flow was to work from a constant fuel level. That in turn required use of a float or weir, supplied either by pump or gravity. If the reliable simplicity of gravity feed was to be used, the tank had to be above the carburetor. That’s where it has been until the very recent past.

The early frames were based upon the classic diamond bicycle frame, but more heavily built-usually with two top tubes, one connecting to the top of the steering head, the other to the bottom. What more natural, safe place for the fuel tank than between these two tubes? As engines grew bigger and needed more of everything, saddle tanks came into being-really two tanks hung over the sloping top frame tube. On most American motorcycles, one side held only fuel, while the other held oil and perhaps reserve fuel. The saddle tank remained the standard tank shape on race and streetbikes for many years. A big change occurred when Irishman Rex McCandless designed the Norton Featherbed chassis, a twinloop design of 1950. The Featherbed tank rested on the (liberally padded) horizontal top tubes, and was held down by a fore-and-aft metal band. This basic form of fuel tank, resting on the main frame tubes, remains a feature of perimeter chassis today.

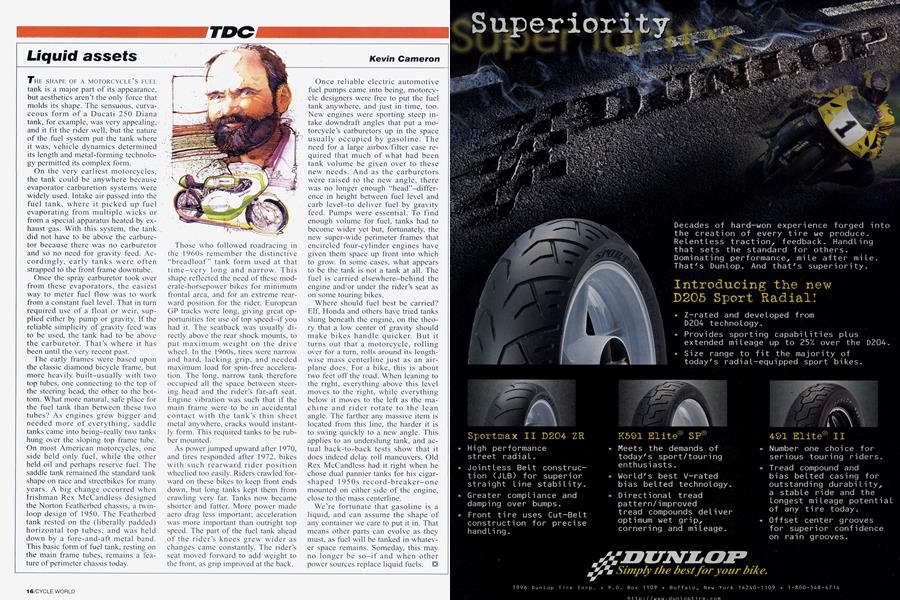

Those who followed roadracing in the 1960s remember the distinctive “breadloaf” tank form used at that time-very long and narrow. This shape reflected the need of these moderate-horsepower bikes for minimum frontal area, and for an extreme rearward position for the rider. European GP tracks were long, giving great opportunities for use of top speed-if you had it. The seatback was usually directly above the rear shock mounts, to put maximum weight on the drive wheel. In the 1960s, tires were narrow and hard, lacking grip, and needed maximum load for spin-free acceleration. The long, narrow tank therefore occupied all the space between steering head and the rider’s far-aft seat. Engine vibration was such that if the main frame were to be in accidental contact with the tank’s thin sheet metal anywhere, cracks would instantly form. This required tanks to be rubber mounted.

As power jumped upward after 1970, and tires responded after 1972, bikes with such rearward rider position wheelied too easily. Riders crawled forward on these bikes to keep front ends down, but long tanks kept them from crawling very far. Tanks now became shorter and fatter. More power made aero drag less important; acceleration was more important than outright top speed. The part of the fuel tank ahead of the rider’s knees grew wider as changes came constantly. The rider’s seat moved forward to add weight to the front, as grip improved at the back.

Once reliable electric automotive fuel pumps came into being, motorcycle designers were free to put the fuel tank anywhere, and just in time, too. New engines were sporting steep intake downdraft angles that put a motorcycle’s carburetors up in the space usually occupied by gasoline. The need for a large airbox/filter case required that much of what had been tank volume be given over to these new needs. And as the carburetors were raised to the new angle, there was no longer enough “head”-difference in height between fuel level and carb level-to deliver fuel by gravity feed. Pumps were essential. To find enough volume for fuel, tanks had to become wider yet but, fortunately, the new super-wide perimeter frames that encircled four-cylinder engines have given them space up front into which to grow. In some cases, what appears to be the tank is not a tank at all. The fuel is carried elsewhere-behind the engine and/or under the rider’s seat as on some touring bikes.

Where should fuel best be carried? Elf, Honda and others have tried tanks slung beneath the engine, on the theory that a low center of gravity should make bikes handle quicker. But it turns out that a motorcycle, rolling over for a turn, rolls around its lengthwise mass centerline just as an airplane does. For a bike, this is about two feet off the road. When leaning to the right, everything above this level moves to the right, while everything below it moves to the left as the machine and rider rotate to the lean angle. The farther any massive item is located from this line, the harder it is to swing quickly to a new angle. This applies to an underslung tank, and actual back-to-back tests show that it does indeed delay roll maneuvers. Old Rex McCandless had it right when he chose dual pannier tanks for his cigarshaped 1950s record-breaker-one mounted on either side of the engine, close to the mass centerline.

We’re fortunate that gasoline is a liquid, and can assume the shape of any container we care to put it in. That means other parts can evolve as they must, as fuel will be tanked in whatever space remains. Someday, this may no longer be so-if and when other power sources replace liquid fuels. □