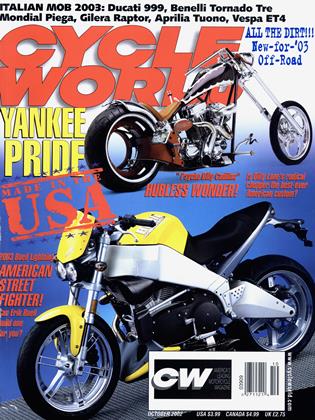

I, Ducatista

UP FRONT

David Edwards

A CRUEL, CRUEL MAN IS PAUL WATTS. Friend of the magazine, one-time collector of oddball Münch Mammuts, he dropped me an enticing note two weeks ago complete with snapshots. Advancing years and a recent knee replacement, he said, meant that his last remaining kickstart classic, a 1974 Ducati 750 GT, was reluctantly on the block. Would I be interested in having a look-see before he put it on the Internet to be pawed over by great unwashed hordes of eBay’ers?3

To a collector, even a casual, eclectic one such as myself, this is better than being privy to the want-ads a day before the newspaper goes on sale.

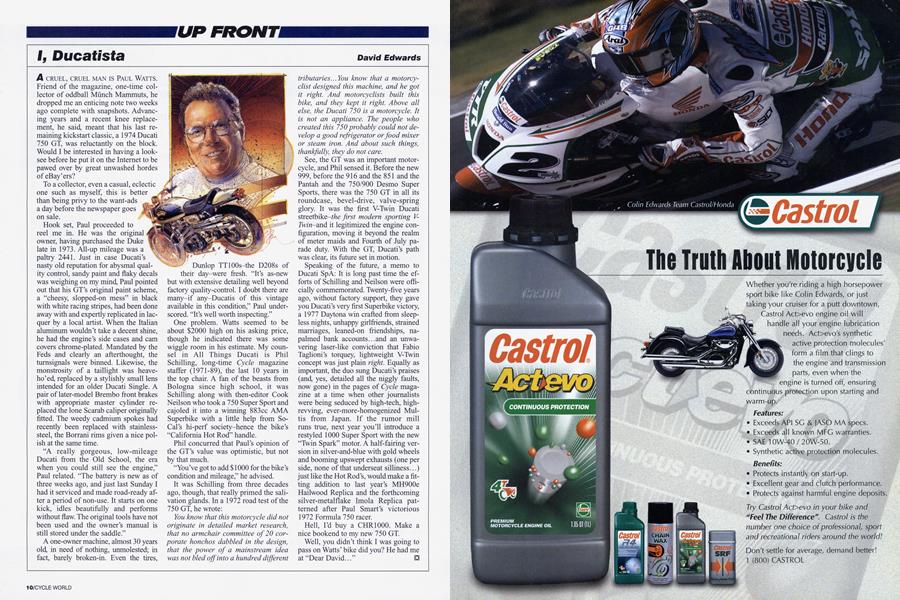

Hook set, Paul proceeded to reel me in. He was the original owner, having purchased the Duke late in 1973. All-up mileage was a paltry 2441. Just in case Ducati’s nasty old reputation for abysmal quality control, sandy paint and flaky decals was weighing on my mind, Paul pointed out that his GT’s original paint scheme, a “cheesy, slopped-on mess” in black with white racing stripes, had been done away with and expertly replicated in lacquer by a local artist. When the Italian aluminum wouldn’t take a decent shine, he had the engine’s side cases and cam covers chrome-plated. Mandated by the Feds and clearly an afterthought, the tumsignals were binned. Likewise, the monstrosity of a taillight was heaveho’ed, replaced by a stylishly small lens intended for an older Ducati Single. A pair of later-model Brembo front brakes with appropriate master cylinder replaced the lone Scarab caliper originally fitted. The weedy cadmium spokes had recently been replaced with stainlesssteel, the Borrani rims given a nice polish at the same time.

“A really gorgeous, low-mileage Ducati from the Old School, the era when you could still see the engine,” Paul related. “The battery is new as of three weeks ago, and just last Sunday I had it serviced and made road-ready after a period of non-use. It starts on one kick, idles beautifully and performs without flaw. The original tools have not been used and the owner’s manual is still stored under the saddle.”

A one-owner machine, almost 30 years old, in need of nothing, unmolested; in fact, barely broken-in. Even the tires, Dunlop TT100s-the D208s of their day-were fresh. “It’s as-new but with extensive detailing well beyond factory quality-control. I doubt there are many-if any-Ducatis of this vintage available in this condition,” Paul underscored. “It’s well worth inspecting.”

One problem. Watts seemed to be about $2000 high on his asking price, though he indicated there was some wiggle room in his estimate. My counsel in All Things Ducati is Phil Schilling, long-time Cycle magazine staffer (1971-89), the last 10 years in the top chair. A fan of the beasts from Bologna since high school, it was Schilling along with then-editor Cook Neilson who took a 750 Super Sport and cajoled it into a winning 883cc AMA Superbike with a little help from SoCal’s hi-perf society-hence the bike’s “California Hot Rod” handle.

Phil concurred that Paul’s opinion of the GT’s value was optimistic, but not by that much.

“You’ve got to add $ 1000 for the bike’s condition and mileage,” he advised.

It was Schilling from three decades ago, though, that really primed the salivation glands. In a 1972 road test of the 750 GT, he wrote:

You know that this motorcycle did not originate in detailed market research, that no armchair committee of 20 corporate honchos dabbled in the design, that the power of a mainstream idea was not bled off into a hundred different tributaries... You know that a motorcyclist designed this machine, and he got it right. And motorcyclists built this bike, and they kept it right. Above all else, the Ducati 750 is a motorcycle. It is not an appliance. The people who created this 750 probably could not develop a good refrigerator or food mixer or steam iron. And about such things, thankfully, they do not care.

See, the GT was an important motorcycle, and Phil sensed it. Before the new 999, before the 916 and the 851 and the Pantah and the 750/900 Desmo Super Sports, there was the 750 GT in all its roundcase, bevel-drive, valve-spring glory. It was the first V-Twin Ducati streetbike-t/ze first modern sporting VTwin-and it legitimized the engine configuration, moving it beyond the realm of meter maids and Fourth of July parade duty. With the GT, Ducati’s path was clear, its future set in motion.

Speaking of the future, a memo to Ducati SpA: It is long past time the efforts of Schilling and Neilson were officially commemorated. Twenty-five years ago, without factory support, they gave you Ducati’s very first Superbike victory, a 1977 Daytona win crafted from sleepless nights, unhappy girlfriends, strained marriages, leaned-on friendships, napalmed bank accounts...and an unwavering laser-like conviction that Fabio Taglioni’s torquey, lightweight V-Twin concept was just plain right. Equally as important, the duo sung Ducati’s praises (and, yes, detailed all the niggly faults, now gone) in the pages of Cycle magazine at a time when other journalists were being seduced by high-tech, highrewing, ever-more-homogenized Multis from Japan. If the rumor mill runs true, next year you’ll introduce a restyled 1000 Super Sport with the new “Twin Spark” motor. A half-fairing version in silver-and-blue with gold wheels and booming upswept exhausts (one per side, none of that underseat silliness...) just like the Hot Rod’s, would make a fitting addition to last year’s MH900e Hailwood Replica and the forthcoming silver-metalflake Imola Replica patterned after Paul Smart’s victorious 1972 Formula 750 racer.

Hell, I’d buy a CHR1000. Make a nice bookend to my new 750 GT.

Well, you didn’t think I was going to pass on Watts’ bike did you? He had me at “Dear David...”

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Leanings

LeaningsA Tale of Two Suzukis

October 2002 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCY-Alloy? Why Not?

October 2002 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

October 2002 -

Roundup

RoundupCruising In Luxury: Bmw R1200cl

October 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupCentennial Harleys

October 2002 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupSpecial-Issue Yamahas

October 2002 By Matthew Miles