TRIUMPH BONNEVILLE

A sliver of the true cross

MARK HOYER

IT WAS WINTER, WHICH WAS DISCONTENT. THE KIND OF WEATHER THAT could make motorcycle riding a mild form of hardship,_something you felt like you were endure, not enjoy. But life is usually a question of attitude. And riding the 2001 Triumph Bonneville in England made me feel so cool my nipples were hard. Or was that the 45-degree air cranked even colder by 80 mph of naked windchill? No rnattei the tact is that I was riding a ncw~Eng1is~ mo in Olde England and the only thing I ished I could ch'i gear-to a suit of flaming kerosene Otherwise, it as a i fi ip for me to this soggy, over-cooled little iock in the North S

I was mentally prepared for the weather (if not quite physically), since at sunset the night before the ride, I peered out the window of my hotel room just in time to see a pigeon land and get blown over by a gust of wind! A crea ture of the sky knocked down by its own medium. Then later, the TV news lady said there'd be 2 inches of rain before dawn, and it was already 12:30 a.m. And this next part I quote (use your best Monty Python cross-dresser tone of voice) because it made me laugh so hard: "There is risk of destruction, and unless absolutely necessary, don't leave your homes." Don `t leave your homes! Nice day for a ride, then. Storm-force (as in hurricane) and gale-force winds hit the southeastern coast hardest, with most of southern England getting pummeled by this powerfifi system to the tune of 11 inches of rain in 24 hours. Flooding was so severe it caused closure of the rail system. Looking on the bright side, the newswoman measured the weather up north in hours of sunshine, the best on the whole island at an impressive 6.9 hours, somewhere on the faraway tip of Scotland. Much more favorable than the 6.9 mm utes of sunlight in which we'd gotten to bask down Oxford way, launching point for our brief 90-mile ride. So Scotland had the weather for once, but the Triumph isn't a Scottish motorcycle. It's English, genuine. In fact, Triumph is the British motorcycle industry, and the weather, well, it was perfect Britbike ambiance, right? Never mind the fact that, according to Triumph, of the 385,000 original Bonnevilles produced from 1959 to 1983, fully 80 percent were sold in the U.S., making some nice toasty-warm locale in our one-time colony just as appropriate for a riding intro, no?

Apparently not, but the 308,000 Bonnies of old that hit our shores helped make the bike one of the most significant in our motorcycling culture. In fact, the Triumph Bonneville in America is really a kind of love object, an icon even, its history and our emotions making it bigger than just a func tional tool for conveyance. The name is pregnant with expectation and colored with nostalgia.

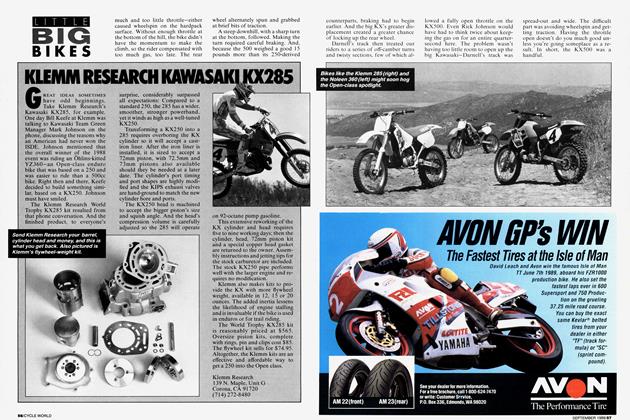

From the beginning, Bonneville meant speed, and the old Bonnie was a perform ance bike. This new Bonneville is not. And certainly with the state of modern motorcy cling, laws and liability, emissions and noise regs, a new Bonneville was always going to be something different.

So sticking with the basic parallel-Twin Bonneville formula-even down to old-style chassis geometry-means this is sort of a British Harley-Davidson, with words like "traditional" and "authentic" instead of "performance" and "technology" being ped dled like crack to the band of merry journos on hand for our first ride.

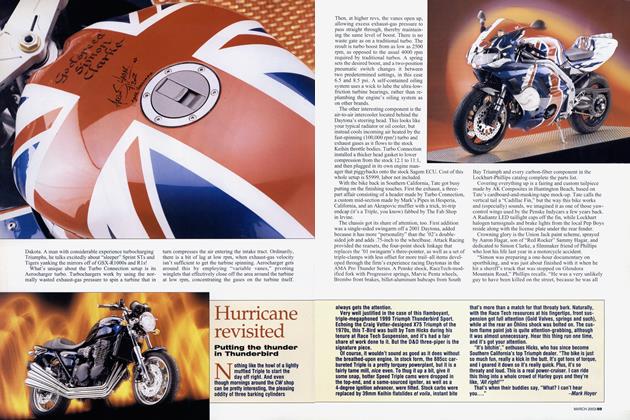

When you gaze upon this Bonneville for the first time in the metal, it is a strikingly correct rendition of an old, late-Sixties ver sion, which was the intent from the bike's design beginnings in 1997. As such, it looks good, better than the first photos suggested it might. And it says "Triumph" on the tank, which meant more than I thought it would. Still, there are places on the Bonneville where the reality of the new and the images of old overlap imper fectly. The emissions reducing air injectors, for instance, poke into the classically shaped cylinder head beside the sparkplugs, while the pair of 36mm Keihin carbs have black-plastic throttle-position sensors stuck on the sides. There's an oil radiator hung under the steering head, this _________

being an air/oil-cooled design. So in some subtle ways, nostalgia meets modem motorcycle in an uneasy tmce across the decades. Still, the overall effect has the right visual feel, and in the same way that a new Sportster isn’t an exact replica of an old one, so this new Bonneville makes its concessions to modem motorcycling.

Perhaps the biggest is the engine, significant in that it’s a new design for Triumph, not a lopped-off Triple or halved Four. Efforts were made to keep the silhouette of the parallel-Twin a rough approximation of the old pushrod unit, while making the insides as fully up to date as possible. So the 790cc, 86 x 68mm two-banger employs four valves per cylinder and a pair of camshafts, but an idler gear (similar to what Suzuki did with the TL1000) allows the drive gears on the cams to be smaller so they can be tucked deeper into the heads and closer together. This makes the whole top-end affair more compact and visually closer to what once was. The cylinder head’s oil-drain tube at the front of the engine was designed to visually mimic the pushrod tunnel of the old powerplant, while the final-drive chain was moved to the right side-contrary to the design of other Triumphs and most modem bikes-so that more traditional-looking engine sidecovers could be used. Of course, it’s got a 360-degree crank at its heart-couldn’t call it a Bonneville otherwise. But this one employs a pair of balance shafts, in addition to long connecting rods, to quell the inherent shaky nature of such a layout.

Quell it does, for that’s the single greatest surprise when you first fire the Bonnie up with the electric leg (no kickstarter): This thing is smoooooth, even with its solid mounts to the double-cradle steel frame. I can see dyed-in-the-woolers complaining about this, but I say thanks for making it so, Triumph. Most of the time when people say “character,” what they mean is “discomfort.” Even Harley had smarts enough to wake up and smell the counterbalancers.

As a result, once we putt-putted our way out of Oxford on wet streets and finally hit the open road (also still wet), engine vibes were minimal, British ambiance maximal.

The pace of the ride was sort of “Hailwood Lite”-sharply brisk, like the weather, with caution tossed in at times for the wet leaves somehow not blown away by the high winds. Being a California kid it was tough to take my mind off the temperature, plus these press-intro group rides are always strangely frantic. Still, all this green, these winding country lanes, the little stone walls, darling villages, thatch roofs-all aboard a for-real new Britbike-began to execute a transposition of my

experience from being one of the interloper to one of soaking into the culture, much like the intermittent rain was soaking into me. Also, the nature of the roads finally made the short gearing of vintage Triumphs seem sensible, even if it was never quite right for America’s hugeness.

Ninety miles isn’t exactly the best opportunity for an exhaustive evaluation of a motorcycle’s performance and character, but within the limited confines of this mileage, the Bonneville appeared L.PUIIII'., v iii~ app~at `.~u to fit nicely into its intended role in the two-wheeled world. The seating position (and seat) is very comfortable, and in the engineering sense the bike feels well-integrated and fin ished. Steering is a little heavy at parking-lot speeds, but overall ease of handling is good. The five-speed gearbox has decent shift quality, and both clutch and brakes have good feel and function.

With some revs behind it, the Bonneville moves along smartly, power taking a notable step up toward the top end. It’s not the incredibly docile lug-meister Kawasaki’s W650 is, but by the same token the Kawi doesn’t rev nearly as quickly at the loud end of the spectrum. Claimed power is 61 bhp at 7400 rpm, with 44 foot-pounds of torque at 3500, which, even with a TransAtlantic Correction Factor, should give it slightly better performance than the W650.

After the pleasantly heavy steak-and-ale pie at the Horse & Hound Public House, I kid napped one of the photogra phers and ditched the rest of the group, partly in an attempt to get photos with sunshine, but also so I could set my own pace on the ride back to Oxford. Motoring back at a more relaxed pace showed suspension compliance is decent, though neither the non-adjustable 41mm fork nor preload adjustable rear shocks will be mistaken for plush. As you might imagine from a chassis with a 29-degree rake, 4.6 inch es of trail and 58.8 inches of wheelbase, lack of stability wasn't an issue, even scraping footpegs rung out in fourth gear. So functionally, there really are no complaints, and in fact the Bonneville is simply pleasant to motor around on, even at a sport ing pace. About the only real dis appointment in the riding experi ence was that the sausage-shaped exhausts are much, much too quiet. It makes the Japanesebike-like whirring of the powerplant the overriding sound at low speeds. Which is why Triumph offers "racing" (ho-ho!) silencers to spice up the horsepower (plus 10 bhp, says Triumph) and add the right kind of sounds. On a related note, judging by the extreme blueing up by the cylin der heads, perhaps double-

JJ~ILL(.4kJ~Y .&~4IJI~_ walled header pipes might have been a good idea, too. But these are small details. In the larger scheme, the image of this bike, the things it evokes, mean more than what it does and how it works doing it. At the core, the $6999 Bonneville is a decently priced, competent means of trans port, a good level of entry for many into real British motor biking. It's sporty, but not a sportbike; you can cruise on it, but it's not really a cruiser. And the elements it feeds in us cannot be measured with radar guns or dynos-the emotions are too deep for detection by ordinary machines. What the Bonneville feels like is a Triumph.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontTales From the Tour

February 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Town Too Far

February 2001 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCGordon Jennings

February 2001 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2001 -

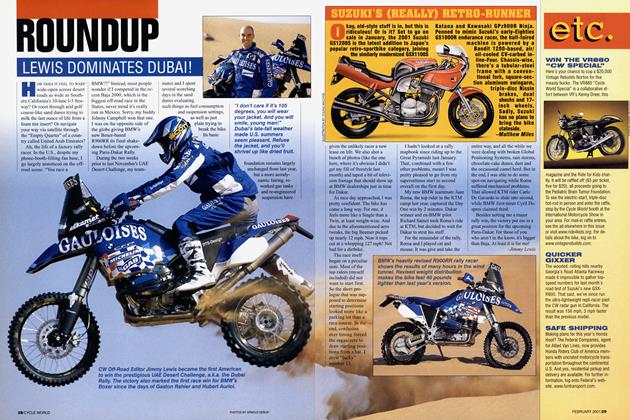

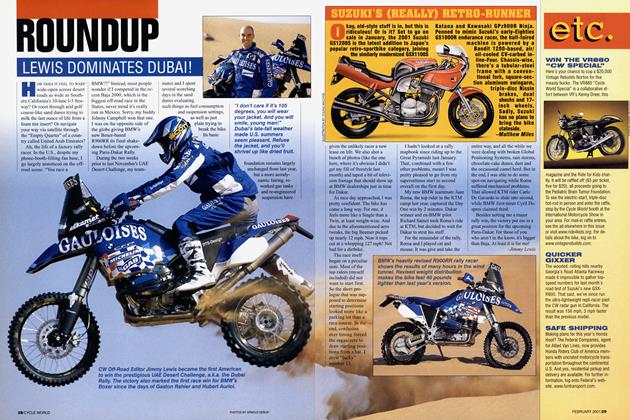

Roundup

RoundupLewis Dominates Dubai!

February 2001 By Jimmy Lewis -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's (really) Retro-Runner

February 2001 By Matthew Miles