Gordon Jennings

TDC

Kevin Cameron

GORDON JENNINGS, PRICKLY GRANDDAD of American motor-journalism, has died of cancer at age 69.

Gordon did everything in his life. He was a technician in the Navy. He raced on two and four wheels. He built racing motorcycles of original design, both two-stroke and four-stroke. He wrote about them and about the engineering principles behind them. Hç was an engineering consultant to highprestige firms. He wrote books, more than 500 magazine articles and technical papers. These activities were for him a feast, a Christmas morning that never ended. Late in life he said, “Lve done all the things I wanted to do.”

In being editor at magazines like Cycle, Road & Track, and Car and Driver, he was never shy about letting us-and manufacturers-know exactly what he thought about any issue. His was a pugnacious personality, ideally suited to his later career as an expert witness, testifying in vehicle-liability cases. There was nothing Gordon liked better than clearly and concisely exposing, usually with humor irresistible even to its victim, the contradictions in someone else’s reasoning. As former Cycle editor and Jennings associate Steve Anderson said to me last night, “Can you imagine the awful plight of an attorney trying to cross-examine Gordon?” Starting in the early ’60s as technical editor for Cycle World, Jennings educated a whole generation of magazine readers with his let’s-do-it enthusiasm for ideas and projects. Many remember his project articles-the home-built roadracing Ducati 250 Single, the Bridgestone 350 “Son of Secret Weapon” with its propensity to backfire its carburetors off, and the famous low-boy, lightweight Harley that may even have deflected the mighty Motor Company slightly from its conservative course. Jennings’ attitude was that we humans can understand technical matters if we think about them-don’t leave it to the “experts.” Nowhere was this made clearer than in his Two-Stroke Tuner’s Handbook. At a time when two-strokes were a mystery to most motorcyclists, his book explained the basics and urged us to take up hacksaw, torch, handgrinder and lathe to make our engines more powerful. It was really a compendium and enlargement upon a series of articles he had written, beginning in the ’60s. His

explanations worked. Thousands of people raised their compression, welded up their own exhaust pipes and reshaped their ports. I know because I was one of them. Gordon’s little book created a new vocabulary, and to this day, when my wife Gwyneth refers to engine jargon, she calls it “talking squishband.”

Like all good practical engineers, Jennings understood physics. His Aermacchi 250 roadracer began with terrible stock carburetion, which he traced to foaming of the fuel from vibration. His solution was to change the carburetor’s natural frequency to something below the engine’s range by wrapping and taping wheel-balance lead onto it. When the bike was sold, the new owner complained that it accelerated but wouldn’t top-end. You guessed it-he had removed the conceptually elegant but visually unappealing mess of tape and lead, thereby recreating the original problem.

Time and again, Jennings solved problems that defied others by just such simple, direct methods. This ability he owed to being both very bright and selfeducated-he didn’t leave that important job to institutions. By this work, and by his clear, enthusiastic writing about it, he became a prime mover in the conversion of motorcycle technology from a messy and very imperfect art into its present, more scientific state.

In the early ’90s, Gordon and longtime girlfriend Karen Green created Wheelbase, an online car-and-bike interactive site that introduced many of the concepts now central to successful Internet businesses. It was too much,

too early, and despite interest from major firms, it never realized its potential. This was characteristic of the man. Ideas were the main thing for him, and he had plenty of them. Beyond a certain point, implementing those ideas interested him less.

I met Gordon Jennings for the first time in about 1973, at an impromptu California luncheon with (then) Cycle magazine principals Cook Neilson and Phil Schilling. I had begun to contribute to Cycle and was definitely nervous about just what my relationship with Jennings would be. He didn’t say a word. I decided I should be the nephew, he the uncle. That worked very well over many years of coast-to-coast telephone friendship.

Neilson, an icon of motor-journalism in his own right, recalls, “In the spring of ’72, the two of us shared an office. That was a dreamy year...all we had to do was write stories, take pictures and fire it all back to New York. It was then that Jennings sort of taught me how to be an editor, but I was having so much fun I hardly noticed.

“If motojournalism developed a bent towards literacy, well, he may not have been the founding father, but he was right there amongst ’em,” Neilson notes.

A favorite Jennings story was of how he finally knew it was time to stop roadracing. After crashing hard at Indianapolis and regaining consciousness on his back, staring up at the ceiling of yet another trackside meat-wagon, his first thought was, “Look at that. They use the same headliner material in all these ambulances. ..” He decided that was enough familiarity with emergency services.

Jennings resumed magazine writing recently, this time for Motorcyclist. In his column he gave voice to a sincere concern that common sense and thoughtful action are being replaced in our world by legislated morality and group thinking. In this he offended some, delighted many, and made all his readers think. The column included his telephone number and e-mail address. Karen relates that people would call and he would talk for hours. Many thanked him for his years of writing. He would reply by thanking them. “Otherwise,” he’d say, “I’d have had to go out and get a job.”

Human life is finite. The human spirit is not.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

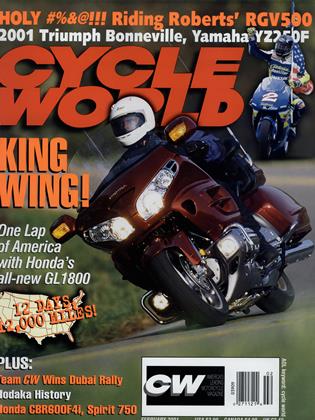

Up FrontTales From the Tour

February 2001 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsA Town Too Far

February 2001 By Peter Egan -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

February 2001 -

Roundup

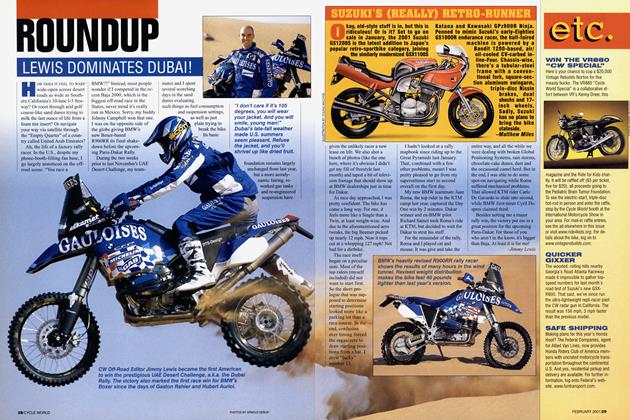

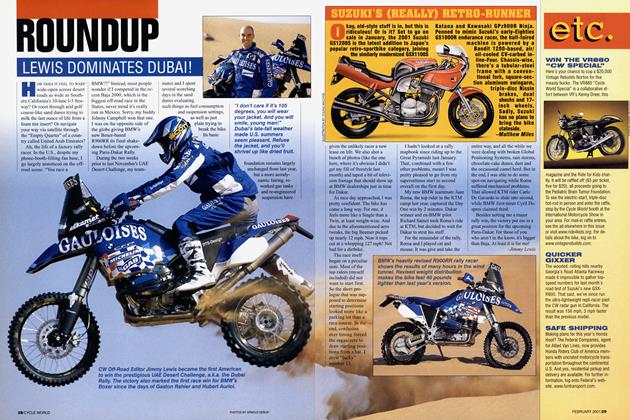

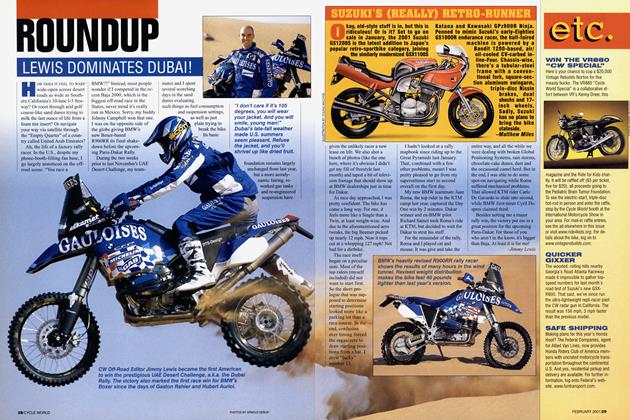

RoundupLewis Dominates Dubai!

February 2001 By Jimmy Lewis -

Roundup

RoundupSuzuki's (really) Retro-Runner

February 2001 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupEtc.

February 2001