The Cyclone

America’s first Superbike

MICHAEL DREGNI

"CYCLONE," IT READ ON THE GAS TANK, and a cyclone it truly was. On the evening of June 21, 1914, rider Jock “Demon” McNeil rolled this new motorcycle to the starting line of the Twin City Motordrome in St. Paul, Minnesota. Straddling their tried-and-true Indian and Excelsior works racers, other riders must have snickered at Demon’s oddball, home-brewed machine. Their laughter was quelled when the green flag fell.

Roaring around the circular, quarter-mile boardtrack, the bike lived up to its name, leaving the others in the breeze. McNeil’s Cyclone won its first race-breaking the track’s 3-mile record en route.

This new machine earned instant respect from one and all. Painted an audacious yellow, it was not the product of one of the famous factories, but a locally made upstart. Below the curlicued “Cyclone” logo on the tank was the maker’s name in small type: “Joems Motor Mfg. Co. St. Paul, Minn.”

The Twin Cities of St. Paul and Minneapolis had long been a center of bike manufacturing, even though the history of the motorcycle itself was young. Among the first firms was the Thiem Mfg. Co., which began around 1900 making motors and complete cycles for other manufacturers and dealers who sold the machines under their own names.

Sadly, Edward A. Thiem was also a pioneer at losing money by building motorcycles. In 1911, the concern was acquired by Fred Joems, the scion of a prominent St. Paul furniture-building family. Joems was the family black sheep, and had little love for dining-room tables or armchairs. He was fascinated instead by the technology of the early automobiles and motorcycles, and so stepped in to mn the newly named JoemsThiem Motor Mfg. Co.

In 1912, the firm launched its single-cylinder Thiem powered by an early sidevalve engine. The sidevalve design was pioneered in the United States by Reading-Standard in 1906, but didn’t win widespread acceptance until Indian converted to sidevalves with its Powerplus of 1916-HarleyDavidson took to sidevalves in 1929. The Thiem sidevalve was the brainchild of factory superintendent Andrew Strand. A recent immigrant from Sweden, Strand was a confirmed tinkerer with a love for doing things differently.

And Strand had another engine he had been toying with.

While the sidevalve Thiem was years before its time, Strand’s new engine was decades ahead.

The engine’s layout followed established American V-Twin architecture; the revolution was in Strand’s overhead-camshaft drive.

Overhead cams themselves were not new. The setup was used on an early French Peugeot race car, among others. But cams were on motorcycles, and the engineering needed to make the system work was intricate and innovative. Strand created a masterpiece. The engine’s overhead cams ran via a series of beautifully machined bevel gears. A bevel gear on the end of the engine-pinion shaft drove shafts running vertically up the right sides of the two cylinders. These powered the overhead cams via another set of bevel gears. Running off a bevel-gear drive on the front cylinder shaft was a shorter shaft that drove the magneto.

The overhead valvegear was also unique to the Cyclone, with rockers pulling the valves down to open them, rather than pushing them open as on other designs. This setup cut valve-guide wear, a common woe for engines of the day.

Strand’s 61-cubic-inch (lOOOcc) engine boasted cast-iron heads, cast-steel cylinders and flat-topped steel pistons-quaint and prosaic specs today, but state of the art for the 1910s. A straight connecting rod nestled inside its forked companion; both were hand-forged steel. The combustion chambers were near-hemispherical, as Strand was a forward-thinking fellow. Power was a suspected 45 at a safe 5000 rpm.

Strand also ported the cylinders, cutting-edge race tuning for the time. Ports at the cylinder bases allowed fast gas extraction, similar to modem two-stroke theory. To balance the subsequent added air intake, the carbs were jetted for a super-rich fuel mix. Problem was, the gases and hot oil landed on the rider’s legs...

Strand’s engine was mounted in a typical rigid racing frame with a single-speed primary and chain final drive to the rear wheel. Brakes were eschewed, as they were considered too dangerous-a distinct possibility considering the quality of brakes of the day and the speeds achieved.

Exactly when the Cyclone prototype was built is tough to pinpoint. Some historians believe it may have been as early as 1912 or 1913. Considering the way the Cyclone lived up to its name in its first race in 1914, Strand must have been perfecting his pride and joy for quite some time before unleashing it.

No matter the exact date of introduction, the Cyclone was the most technically advanced motorcycle of its era in the United States-and probably the world.

After winning its premiere, the Cyclone was back on the pine boards June 24, 1914. Demon McNeil shattered the Twin City Motordrome’s 2mile record and won one heat of a three-heat race over veteran rider Larry Fleckenstein aboard his factory Indian.

Throughout the summer of 1914, the Cyclone’s consistency in winning races and setting records became almost tedious. On June 29, it broke the motordrome’s 1-mile record with a speed of 97.29 mph on McNeil’s way to winning five heats and races. On July 1, the Cyclone cut its own 2-mile record and won five more heats and races. For Independence Day,

McNeil and the Cyclone slashed the world’s 4-mile record for quarter-mile motordromes. On July 8, the duo tore apart the 2-mile record yet again. As the local newspaper noted in a fine flourish of purple prose, “McNeil was

riding his Cyclone racing machine like a madman.”

Later in 1914, Fleckenstein parked his Indian and joined McNeil on a Cyclone at the new Omaha, Nebraska, motordrome. McNeil himself rode a mile dash in 32.4 seconds for a record speed of an astonishing 111.1 mph, far beyond the recognized world record of 93.48 mph set by Englishman S. George on an Indian, faster than Lee Humiston’s 100-mph mark on an Excelsior.

The Federation of American Motorcyclists refused to hail the Cyclone’s achievement, however. Board-track speeds were not recognized by the FAM, which anyway seemed suspicious of such a high margin of speed-more than 10 percent!-over other racebikes of the day. But everyone knew the truth: The Cyclone was unofficially the fastest motorcycle in the world.

In 1915, McNeil was hired away from Joems to serve as development engineer at Excelsior, and his saddle was eagerly taken by veteran board-tracker Don Johns. On January 31, 1915, Johns appeared with his new Cyclone at the 1 -mile dirt-track in Ascot, California, for a 100-mile race. During the day’s prelude contest, Johns chalked up a new 10-mile record.

But it was in the 100-miler that Johns established the Cyclone indelibly in the minds of its rivals. He blazed away from the field and lapped every other rider. Then, his engine cut out with dirt clogging his carb at the 50-mile mark, forcing him to retire. But the point had been made.

Other riders sought glory aboard the Cyclone in 1915, as well. At the July 4th 300-mile National Championship in Dodge City, Kansas, Dave Kinnie set the fastest lap in qualifying at 88.5 mph. During the race, Johns and his Cyclone retaliated with a 90-mph lap. As Motorcycle Illustrated enthused, “Johns’ work was nothing short of spectacular and it was generally understood that he was gaiting himself for a new 100-mile record.” Unfortunately, about three-quarters of the way through the race, Johns’ Cyclone faltered and he lost the lead, eventually retiring along with Kinnie.

Engineering the development, production, sales and support of a new motorcycle marque-as well as operating a national racing team-was a herculean effort at the best of times. The challenge was too much for Fred Joems, and on October 19, 1915, the firm announced that it was ceasing motorcycle production. The Cyclone was no more.

Joems had done battle as David against the Goliath of the established Indian, Excelsior and Harley-Davidson factories for two years. Earlier in 1915, Cyclone had debuted two production models alongside its factory racers: the road-going “Model 7, C-15” with rear swingarm leaf suspension, and the privateer racer’s unported “Model 7, R-15 Stripped Stock Model.” The number of Cyclones built and sold during the one or two years of production is unknown, and only a handful exist today.

Motorcycle historian Jerry Hatfield traced the Cyclone’s history following Joerns’ closure:

In 1916, a group of Chicago investors bought Joerns’ assets with grand plans to revive the marque. The plans never materialized, and the group sold out to two partners who moved the operation to Cheboygan,

Michigan, in 1920.

In 1920-21, another group rumored to be associated with General Motors bought the assets and built a factory in Benton Harbor, Michigan. Again production plans faltered. In 1923, the Reading-Standard company raced a Cyclone copy based on engine castings purchased from Joems.

And with that, the Cyclone name was finally laid to rest.

The Twin City Motordrome was razed after the decline of board-track racing in 1916 following a series of horrific accidents and deaths at “saucer tracks” around the United States. Preachers, journalists and concerned do-gooders joined voices in shouting down the brief spectacle that was motordrome racing. By the dawn of World War I, like the Cyclone, it was all history. □

This story was excerpted from Michael Dregni ’s new book, The Spirit of the Motorcycle, available in bookstores or from Voyageur Press, 800/888-9653. Cycle World would like to thank Daniel Statnekov for providing his 1915 Cyclone factory board-tracker, shot on location at the Otis Chandler Vintage Museum, Oxnard, California.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

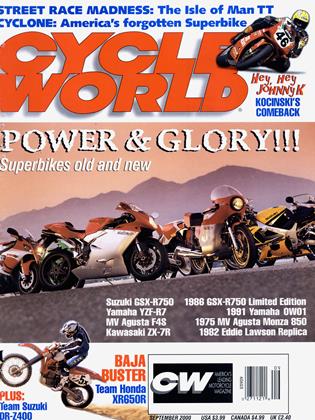

Up Front

Up FrontMr. Bonneville

September 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCafé Americano

September 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCScrewed And Shrunk

September 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

September 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupAprilia Takes Charge

September 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Roundup

RoundupYamaha's Screamin' Little Thumper

September 2000 By Jimmy Lewis