New Ideas In Electronics And Clothing, Wheels

CYCLE WORLD hears about many new products each month. We choose the ones we think would be of the most interest to our readers. We obtain a sample we can test and proceed with an evaluation that is just as thorough as the one we give the bikes we test. We can't test everything, but if you have a preference drop us a line and we 'll do our best to obtain the product and pass on our test information.

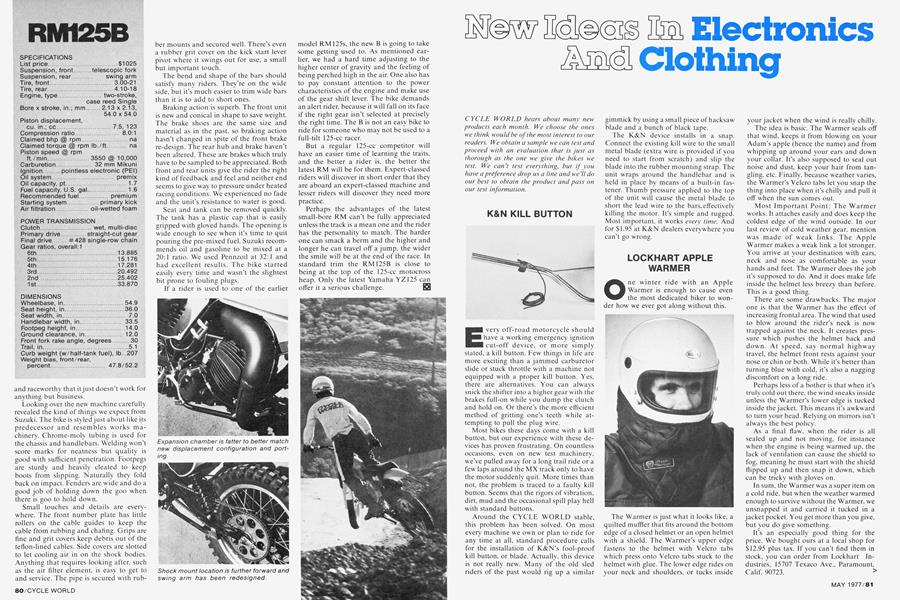

K&N KILL BUTTON

Every off-road motorcycle should have a working emergency ignition cut-off device, or more simply stated, a kill button. Few things in life are more exciting than a jammed carburetor slide or stuck throttle with a machine not equipped with a proper kill button. Yes, there are alternatives. You can always snick the shifter into a higher gear with the brakes full-on while you dump the clutch and hold on. Or there’s the more efficient method of gritting one’s teeth while attempting to pull the plug wire.

Most bikes these days come with a kill button, but our experience with these devices has proven frustrating. On countless occasions, even on new test machinery, we’ve pulled away for a long trail ride or a few laps around the MX track only to have the motor suddenly quit. More times than not, the problem is traced to a faulty kill button. Seems that the rigors of vibration, dirt, mud and the occasional spill play hell with standard buttons.

Around the CYCLE WORLD stable, this problem has been solved. On most every machine we own or plan to ride for any time at all, standard procedure calls for the installation of K&N’s fool-proof kill button, or blade. Actually, this device is not really new. Many of the old sled riders of the past would rig up a similar gimmick by using a small piece of hacksaw blade and a bunch of black tape.

The K&N device installs in a snap. Connect the existing kill wire to the small metal blade (extra wire is provided if you need to start from scratch) and slip the blade into the rubber mounting strap. The unit wraps around the handlebar and is held in place by means of a built-in fastener. Thumb pressure applied to the top of the unit will cause the metal blade to short the lead wire to the bars, effectively killing the motor. It’s simple and rugged. Most important, it works every time. And for $1.95 at K&N dealers everywhere you can't go wrong.

LOCKHART APPLE WARMER

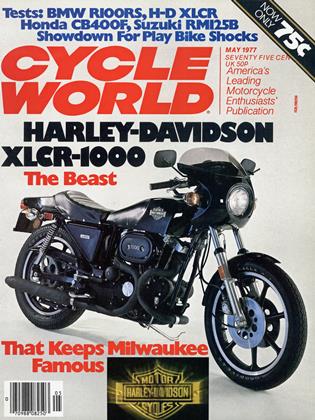

One winter ride with an Apple Warmer is enough to cause even the most dedicated biker to wonmost to wonder how we ever got along without this.

The Warmer is just what it looks like, a quilted muffler that fits around the bottom edge of a closed helmet or an open helmet with a shield. The Warmer’s upper edge fastens to the helmet with Velcro tabs which press onto Velcro tabs stuck to the helmet with glue. The lower edge rides on your neck and shoulders, or tucks inside your jacket when the wind is really chilly.

The idea is basic. The Warmer seals off that wind, keeps it from blowing on your Adam’s apple (hence the name) and from whipping up around your ears and down your collar. It’s also supposed to seal out noise and dust, keep your hair from tangling, etc. Finally, because weather varies, the Warmer’s Velcro tabs let you snap the thing into place when it’s chilly and pull it off when the sun comes out.

Most Important Point: The Warmer works. It attaches easily and does keep the coldest edge of the wind outside. In our last review of cold weather gear, mention was made of weak links. The Apple Warmer makes a weak link a lot stronger. You arrive at your destination with ears, neck and nose as comfortable as your hands and feet. The Warmer does the job it’s supposed to do. And it does make life inside the helmet less breezy than before. This is a good thing.

There are some drawbacks. The major one is that the Warmer has the effect of increasing frontal area. The wind that used to blow around the rider’s neck is now trapped against the neck. It creates pressure which pushes the helmet back and down. At speed, say normal highway travel, the helmet front rests against your nose or chin or both. While it’s better than turning blue with cold, it’s also a nagging discomfort on a long ride.

Perhaps less of a bother is that when it’s truly cold out there, the wind sneaks inside unless the Warmer’s lower edge is tucked inside the jacket. This means it’s awkward to turn your head. Relying on mirrors isn’t always the best policy.

As a final flaw, when the rider is all sealed up and not moving, for instance when the engine is being warmed up, the lack of ventilation can cause the shield to fog. meaning he must start with the shield flipped up and then snap it down, which can be tricky with gloves on.

In sum. the Warmer was a super item on a cold ride, but when the weather warmed enough to survive without the Warmer, we unsnapped it and carried it tucked in a jacket pocket. You get more than you give, but you do give something.

It’s an especially good thing for the price. We bought ours at a local shop for $12.95 plus tax. If you can’t find them in stock, you can order from Lockhart Industries, 15707 Texaco Ave., Paramount, Calif. 90723. >

YOKOHAMA 23-IN. TIRE

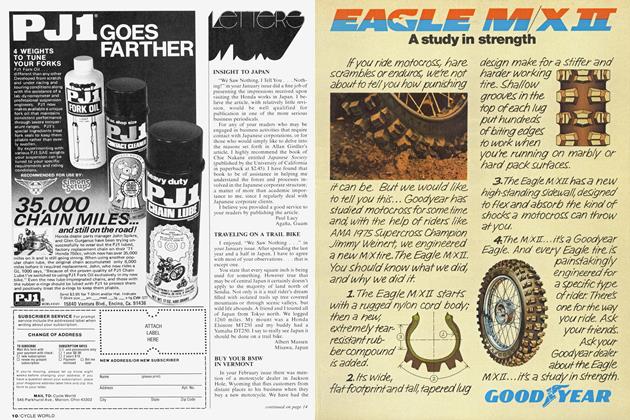

Yokohama’s 23-in. tire first appeared last year on the European motocross circuit, the natural place for something new and different. The larger tire was an innovation, one of many experiments which appear (and usually disappear) in racing every year. The larger tire showed up next in a news release. Yokohama and D.I.D. are offering the 23-in. tire and matching rim for sale. Further, the companies expect the new front wheel combination to become a standard, to do to the 21-in. wheel what the 21 did to the 19-in. wheel, that is, make it obsolete.

How? Call it a trend or a pattern. From 19-in. to 21-in. to 23-in. diameter wheels is a matter of increasing rolling diameter. A 300x21 Yokohama knobby tire has a diameter of 27.5 in. The 300x23 tire has a diameter of 29.5 in. The designer’s reason is that a larger rolling diameter is less affected by surface bumps while providing more accurate steering control. Also, the more slender tire provides less floatation in turns, giving needed side bite for turning traction. This is all very logical.

When the 300x21 wheel and tire became the standard, it was assumed that the combination was as high as a motorcycle tire should be: The taller the wheel, the higher the bike. Not long ago high motorcycles were not considered to be a good thing.

Since then, we’ve seen the revolution in wheel travel, bringing in turn higher racing bikes. Longer travel has increased speed more than higher centers of gravity have slowed them down. We’re willing to swing up onto a 36-in.-high saddle to get the benefits of smoother, more controlled wheel travel.

A taller tire can work against long travel. If the axle will travel 10 in. closer to the triple clamps, then the machine had better have at least 11 in. between the tire tread and clamps or the two will come together and the bike and rider will come apart, as in over the bars. Further, with everything else equal, the taller tire raises the entire bike. We know there’s bound to be a limit. At some point even a motocross racer can be too tall. When that limit is reached, so will the limit of suspension travel be reached. It will be time to look for another advantage.

Which brings us to the Yokohama 23-in. tire. The arrival of the tire brought an immediate reaction: How well does it work?

Yokohama provided the tire, D.l.D. the rim. We had the rim laced to a spare front hub for our Suzuki PE250, which lives in our shop for just such occasions. Off we went for some cross-country and motocross experiments.

During the cross country and desert riding portion of the test, the PE was hauled to the test site equipped with an original equipment 300x21 tire mounted and the Yokohama 300x23 stowed in the back of the van. The reason for this move was that one of the office skeptics felt that perhaps what little, if any difference the new tire would make might be impossible for the average rider to perceive. So, during the cross-country testing, two of the four riders did not even know what was being evaluated.

Each rider took the stock machine out for a loop through the desert. (We used the same course used for the shock test elsewhere in this issue.) After this brief familiarization, the unknowing half of the test team took a walk while the Yokohama was fitted to the PE250. (The 23 is hard to spot unless rolled up next to another conventional tire for contrast.) Again, all four pilots took off on their laps around the course and were interviewed separately for their impressions of the tire, or in the case of the two, to see if they noticed anything at all. To our surprise, each one came in with nothing but praise for the improved handling of the bike. Even the two blind riders pulled up and wanted to know “What the hell did you guys do to the front of the bike? It was hard to believe I was on the same scooter.”

Every rider agreed on the basic qualities of the tire. The first thing noticed was on bumpy terrain. Any size or kind of bumps. The 23 was smoother. When hitting a series of bumps, or whoops, the big tire would roll through rather than crunch over. When the more skilled rider hit the same series with the front end light, he could still feel the added rolling diameter of the Yokohama soaking up what was left.

The same condition was noted on the motocross track. Most tracks seem to develop skitter bumps, caused by wheels bouncing under braking and acceleration on either end of a turn. Nobody likes them, but if you ride MX, you ride skitter bumps. The Yokohama 23 just eats ’em up, and cuts feedback through the bars nearly in half.

Our riders just couldn’t believe the overall improvement made by the tire. In turns the 23 delivers more side bite. The cross section width is still 300 size but the added length of the contact patch makes the tire dig harder in tight turns, thus preventing washout. Using just the front brake, the 23 pulled the Suzuki to a stop in a measurably shorter distance.

One of the riders said that he liked the tire, but he wouldn’t use it on his bike because he likes to ride sandwashes. Most desert riders use a 350 front tire for such purposes. A 350 adds some floatation to the front end in deep sand (just the opposite of what you want in turns) to keep the bike from shaking its head down a wash. To check this rider’s theory, we unloaded another front wheel assembly from the van. This one carried a 350x21 desert tire. The PE was run up and down the nearest wash first with the stock 300, then the 350 and last with the 300x23. Part of the desert rider’s theory was correct. The stock 300 was a handful. It knifed into the sand even with the rider’s weight on the rear of the seat. Next the 350. It was much better. The front of the bike would stay more or less on top of the sand, allowing improved straight-line control. The problem with the 350 tire is that at the end of the straight, when you pitch the bike into a deep sandy turn, the wide tire still wants to float, causing the front to slip from its line.

The 300x23 came next. The 23 delivered the best features of both sizes. The added rolling diameter helped keep the tire on top of the sand in the straights. In turns tried, the 300’s side bite came into play and the Suzuki would stay on a line right through the turn. Everyone was impressed.

The very next weekend, the 23 displayed a trait that was disliked. A member of the staff was out for a trail ride and about 20 miles from the van when a rock bruise punctured the tube. It was then discovered that the Yokohama 23 was not designed to be ridden flat. It was all the poor fellow could do to get back to the truck. Although made with 4-ply construction, the Yokohama is quite thin, no doubt to offset any weight penalty for its larger diameter. But when it goes flat, it goes FLAT! In fairness, we cannot find too much fault. The tire was designed for motocross, not cross-country. And in MX racing, you don't have far to hike if a tire goes flat.

Before testing this tire, it was planned to modify the forks of our PE250 to give 8V2 in. of travel (IV2 in. is stock). These plans have changed and the forks will remain stock in the travel department. With the Yokohama 300x23 tire, lxh in. is all the bike needs. At IV2 in., the forks will be more rigid, and the Yokohama’s abilities through the rough more than offset the advantage of another inch of travel.

Now. We can fairly report on how this new idea worked on one motorcycle under one set of conditions. We’re willing to edge forward from that, with an educated guess: The 23-in. tire and wheel will improve the handling of a late-model machine like the PE250. The added cornering power and control will make up for the extra inch of ride height in front.

Before you whip down to the dealership with cash in hand, though, make sure the tire will work safely on your bike. At full fork compression, some machines do not have enough clearance for the tire. To check your bike, set the machine on a box with the front wheel just off the floor. Remove both fork caps and slide out the springs. Then slowly push the wheel up as far as it will go, and measure the distance between the axle centerline and the inside of the fender. The Yokohama measures 14.85 in., so allow at least 15 in. of clearance for safety. Do this first and save the embarrassment of endoing smartly the first time you bottom the front end of the bike.

In developing this new tire concept, the folks at Yokohama have worked in cooperation with the Diado Corporation. Diado is offering a D.I.D. rim to go with the tire. Yokohama also stated that spoke kits are in the making for most popular applications. For our test we used a custom set of super stainless 9-gauge spokes from Hallcraft’s Industries, Inc., 244 Millar Ave., El Cajon, Calif. 92020. These heavy duty spokes were laced to the D.I.D. After about 25 miles of riding they were tightened again and have been trouble free ever since.

The tire, wheel and assembly work will set you back close to $80, which is a lot to pay . . . unless improved handling is worth it to you.

We suspect the larger tire would also improve the handling of older play bikes, although because they have less wheel travel and thus less clearance between tread and triple clamps, they may have difficulty wearing the 23-in. tire. And raising the front end by an inch will affect rake and trail and may cause handling changes which offset those brought by the new tire.

In general, we can predict even less. From one group we hear predictions that wheel travel has reached its limit and that the larger tire is the winning device for the future. From another quarter comes a prediction that wheel travel will be so important that in order to gain clearance for 12, 13 or more inches, we’ll switch back to the 19-in. wheel, or smaller.

So. 1) The Yokohama 23-in. tire improved our Suzuki PE250’s handling. 2) If you like to experiment, the 23-in. tire may do the same for your dirt bike, and 3) We’ll know in a year or so whether the larger tire was a racing breakthrough or an idea which didn’t work out. S3