RACE WATCH

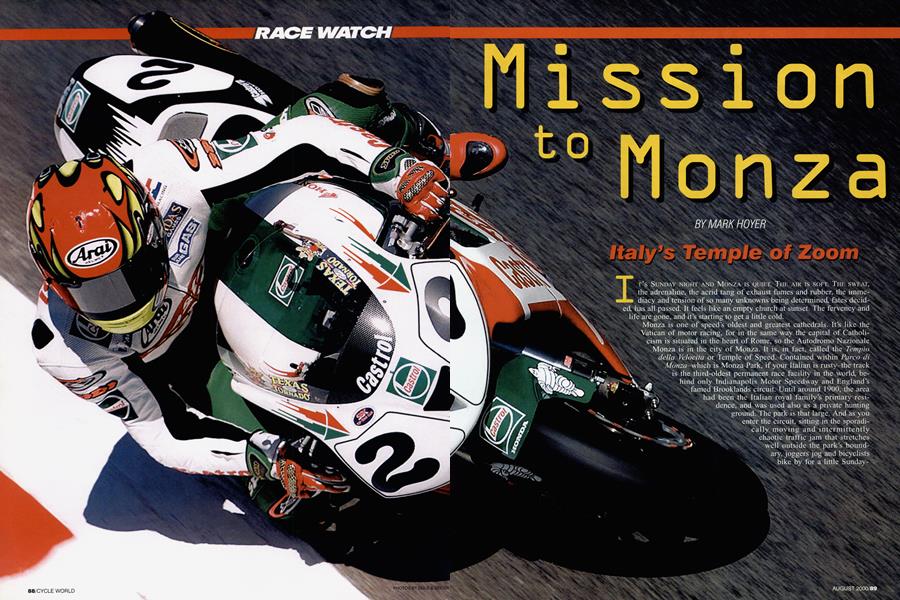

Mission to Monza

MARK HOYER

Italy's Temple of Zoom

IT’S SUNDAY NIGHT AND MONZA IS QUIET. THE AIR IS SOFT. THE SWEAT, the adrenaline, the acrid tang of exhaust fumes and rubber, the immediacy and tension of so many unknowns being determined, fates decided, has all passed. It feels like an empty church at sunset. The fervency and life are gone, and it’s starting to get a little cold.

Monza is one of speed’s oldest and greatest cathedrals. It’s like the Vatican of motor racing, for in the same way the capital of Catholicism is situated in the heart of Rome, so the Autódromo Nazionale Monza is in the city of Monza. It is, in fact, called the Tempio della Velocita or Temple of Speed. Contained within Parco di Monza-which is Monza Park, if your Italian is rusty-the track is the third-oldest permanent race facility in the world, behind only Indianapolis Motor Speedway and England’s famed Brooklands circuit. Until around 1900, the area been the Italian royal family’s primary residence, and was used also as a private hunting ground. The park is that large. And as you enter the circuit, sitting in the sporadically moving and intermittently chaotic traffic jam that stretches well outside the park’s boundary, joggers jog and bicyclists bike by for a little Sundaymorning exercise, seemingly unaware and undisturbed by the fact that a World Championship motorcycle racing event is taking place in their leisure zone. Imagine if there were a racetrack in New York’s Central Park, except that motor racing is as regular a part of life in Italy as breakfast.

Amid all the grand old shade trees and paths and the current 3.6-mile circuit runs the infamous old elevated banking. This is so steep at the top that it is difficult to stand-your shoes slip on the severe angle. To stay up there, where the banking crosses over the straightaway that leads to the Ascari Chicane and gives you a good view, you have to hold onto the rusty guardrail that seems wholly insufficient for the duty it was supposed to perform, which was to keep cars from flying off into the treetops. The railing looks too frail and low. It is terrifying to conceive of racing on , this banking. And perhaps that’s exactly why they don’t race on it anymore. Colin Edwards said he loves this place, and goes out to visit the old track every year. “It’s awesome-just the trees and the banking. I just go out there and veg.”

An amazing place, Monza. The World Superbike congregation brought its color and spectacle and human drama to Monza for its fifth round. The season thus far has been wonderfully chaotic and full of interesting events-injured stars, locals beating up on series regulars, underdogs winning in the face of long odds, a drug controversy and a little dose of preseason brain surgery thrown in for extra flavor. All told, each of the seven manufacturers had taken a win-even Bimota and Anthony Gobert have had a taste of victory.

What’s been clear so far, and was underlined at Monza, is that Castrol Honda’s Colin Edwards is aiming at a championship, riding a bike that apparently has no weaknesses. He was unerringly fast in regular qualifying and took his third Superpole of the season. Much was made of the RC51 ’s top speed at super-fast Monza-it is slower only than Hockenheim. But Edwards pointed out that while, yes, during regular qualifying when he could get a good draft he’d push past 190 mph, a look at the lone-rider Superpole peak speed was a better vision of reality: 12th fastest at 178 mph. The Ducatis, it turns out, had the highest speeds during Superpole. So much for speed charts, eh?

I asked Edwards what he thought was the principle advantage of the RC51 over the RC45. “It doesn’t try to kill you in every corner,” he said with a smile, though only half-joking. He then added, “It actually wants to > turn instead of go straight like the RC45. And where you had to wait for the 45 to settle down exiting the chicanes, you’re already on the gas and going on the Twin.”

In a place where drafting is so important-one of the few tracks on the calendar that you spend more time upright than leaned over-someone asked if Edwards thought it would be possible to break away from the pack.

“When you’re going as fast as I am, it is,” he had said. And God knows he tried, no doubt especially motivated by the two wins Carl Fogarty picked from the Texan’s pocket here in 1999. In the first race, Edwards got in front by the second chicane and was making time on the rest of the field soon after. Then, Suzuki Alstare’s Pier-Francesco Chili started putting on his divine display, the magnitude of which is re-

vealed in the fact that his fastest race lap was some six-tenths faster than anything Edwards had done all weekend, and more than 1 second faster than Troy Corser’s 1999 lap record. All this on last season’s yet-to-be-upgraded GSX-R, with race tires, and more than halfway though the 18-lap race!

Hey, Frankie, where did you find those lap times?! “I brake very, very hard.” Quite so. The pace slowed when Chili caught up-“We both deserved a rest,” said Edwards-and the duo danced around trading the lead with a sort of, “No, no, after you, please!” character. On the last lap, Edwards was in front as they headed toward the Parabólica, the sweeping final corner, when Chili-no doubt braking very, very hard-passed the Honda rider on the way in and led to the line on the way out. The Italian won by a molecule in a photo finish.

Chili cried during the subsequent press conference in a beautiful display of emotion that just seemed so very right for Italy. It is part of what makes Chili so cool. He glides through the Monza paddock like a leather-clad Pope, except he’s part James Bond and part rock star, too, all while remaining human and eminently approachable. But maybe that’s what a motorcycle racer is in Italy-all that. A banner hung over the track fencing read, “Frankie-stein, il monstro di Monza,” and the fans were organized enough to form a giant tricolore Italian flag comprised of colored smoke bombs.

Edwards and Chili made the second race mostly their own as well, and again played games with the lead. Edwards led into the final stages, but as Chili tried to close the gap on the final lap, a mistake kept him just out of striking distance. The Italian was just threehundredths of a second behind at the line in another photo finish-a Japanese V-Twin on the top step of the podium in Italy, shared, as in the first race, with two inline-Fours, Chili’s Suzuki and Akira Yanagawa’s Kawasaki.

Sitting on the long flight to Europe, I thought I might ask Edwards if it as harder to race with the factory acatis now that he is on a motorcycle ostensibly similar. But then I realized, once I got to Monza, that he hasn’t really had to race with one. No, the season thus far for the Brigada Rossa has not been a good one. Carl Fogarty broke his arm and hit his head hard in Australia, the second round, and rumors continued to swirl about early retirement. What’s left for him to prove, right? Maybe that he can still win, and the feeling from those who know him is that he will return. He was described as “angry” at Donington by an associate. The team, meanwhile, is in chaos, scrambling to reestablish its position as a force while American Ben Bostrom tries to find his way in his first season on the world stage.

Bostrom is clearly struggling. What’s up, brother? “When I first came over here for testing, things were going really good. I was fast,” he said. “Then, I had seven or eight crashes and lost confidence in the bike. I’m getting it back now.”

You can hear in Bostrom’s voice how badly he wants to improve, but after a seventh and a 10th in Monza, he looked like a pile of cigar ash in leathers. Part of the problem, he says, is how many new questions there are, because things are definitely different. Example? “We have 40 rear tires to choose from. In AMA, we usually

had three.” This is emblematic of Bostrom’s trouble. Confidence has returned in part because he adopted the front-end setup he used in AMA racing, although this steep-rake, shorttrail setting is contrary to the accepted recipe for Ducati success on fast European-style tracks, which

most agree demand a slower geometry and higher corner speed. Time will tell what works for Bostrom.

Team manager Davide Tardozzi still was paying lip-service to what has been the company line about Bostrom all along: This is just a learning year. “Laguna will be the

first time we can ask him to prove anything,” Tardozzi said. “For the rest of the rounds, I just ask him to enjoy his ride, do whatever he wants. People think if you are not winning by

the second race, you are shit. All this is normal for us here, but everything is new for him. Look at Mick Doohan-it took him a long time to get his first win in GPs.” Tardozzi’s mood and body language after the second race belied the “no-pressure” mantra.

As for the situation with Fogarty, Tardozzi was succinct: “We are praying to God to heal the bone! It is getting better, but we will only have him come back if it is perfect. We will have private tests to make sure he is fast. He must be able to win.” In the meantime, Australian Troy Bayliss, the busiest man in motorcyele racing at the moment, has been flying between his job at Vance & Hines Ducati in the States and the factory team overseas, filling in for the fallen Fogarty. Bayliss’ first outing at Sugo, Japan, ended in a pair of «frxrashes after he was hit at the start of both races-by the same rider! He was revelation in Monza, however, constentlv amazing on the brakes while running with the leaders in qualifying and both races. Honda’s Aaron Slight, still getting back up to speed after his pre-season brain ; surgery, was being polite r when he said Bayliss was “more disciplined” on the brakes than he wanted to be. Indeed, Bayliss took the lead in race two with serious style, passing four riders while braking for one of the chicanes. If it was a mistake, it sure didn’t look like one. I asked him what he owed his braking advantage to and he said, simply, “I reckon I just squeeze a bit harder, mate!” and then continued to downplay the whole show, despite the fact he said he’d never really raced on Michelins or at Monza before. His weekend ended with a pair of fourthplace finishes and a new job on the factory World Superbike squad. What about his Vance & Hines ride in the AMA championship? It appears that John Kocinski-he of the previous 250 GP and World Superbike championships-will take over the newly vacant seat, which should be very interesting for us here.

Amid all these Ducati team machinations, former 996 factory rider and World Superbike Champion Troy Corser has been making the Bolognabased company look bad for firing him last year with some impressive performances on his Aprilia RSV Mille. Although we in America are mostly unfamiliar with Aprilia, it is not a small company. Think of it as compact. Also think of it as aggressive, for it is not without aggression that this Italian manufacturer has given the Japanese factories fits for so long in the 125 and 250cc Grand Prix class, and it looks well on the way to doing the same in the Superbike ranks. The team has made remarkable progress, and Corser has acquitted himself well, although Monza demands horsepower the Aprilia doesn’t yet produce. Still, he’s put the bike on pole twice, taken one win and was fourth in points after Monza. “The bike is completely changed from when I started,” Corser said. “The geometry, the ride height, the twin exhaust, everything. It’s difficult because every track is new for me on this bike. We don’t have a baseline, so I just start with the setup from the last track. And I’m still adjusting to Dunlops-the way they feel and slide is totally different than Michelins. But the real problem is that as we progress, so does the competition.”

For now, Corser really isn’t a threat in the championship, for that battle has developed into a three-horse race with Edwards, Chili and Yamaha’s Noriyuki Haga pulling ahead of the others. Haga’s early season was excellent, the Japanese rider taking a win at the opening round and leading the championship coming into Italy. Monza, however, was rough. The shift linkage failed in the first race, and his clearly underpowered YZF-R7 carried him to fifth the second time out. Also, results of a second blood test became public at Monza, and were positive for ephedrine, just as the first sample, taken at Kayalami, had been. This threw the Japanese rider’s championship future into question, for while the points Haga has already scored are safe, disciplinary action could take the form of an up to three-month ban from racing, although the FIM has the option of doing nothing. So Haga was pretty low-profile, and when I did try to have a word with him, his English wasn’t as good as I remembered from the Suzuka 8-Hour where I talked to him last year.

But that’s all part of the fun and drama of racing, for what would it be without its personalities? Yes, Monza’s seen a lot of classic races, no doubt, the eerie echoing sounds of motorcycles and cars reverberating though trees, chilling spines and thrilling fans for eight decades. An amazing, hallowed place, Monza. But while places can be holy, it’s the people who make the church.

This year, an Italian homeboy and a long, tall Texan did the old temple proud. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNed's Sled

August 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCharacter Infusion

August 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCTwo Crankshafts?

August 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupEurope Gets Naked!

August 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupIndian's Sporting Scout

August 2000 By Wendy F. Black