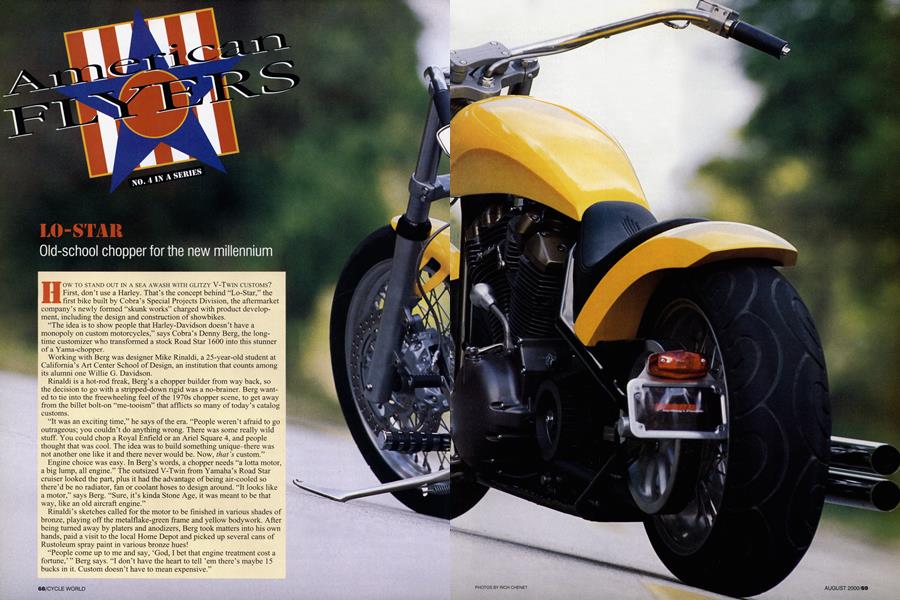

LO-STAR

American Flyers NO.4 IN A SERIES

Old-school chopper for the new millennium

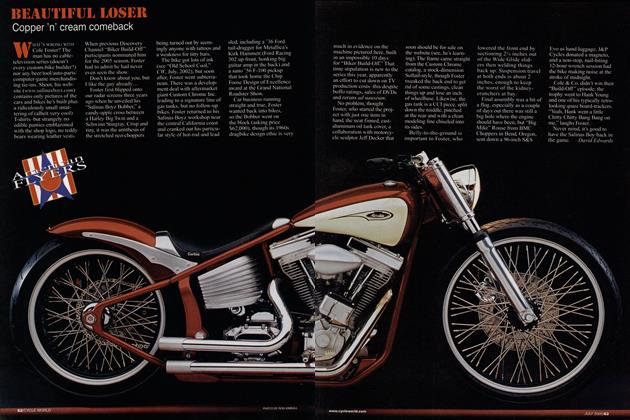

HOW TO STAND OUT IN A SEA AWASH WITH GLITZY V-TWIN CUSTOMS? First, don’t use a Harley. That’s the concept behind “Lo-Star,” the first bike built by Cobra’s Special Projects Division, the aftermarket company’s newly formed “skunk works” charged with product development, including the design and construction of showbikes.

“The idea is to show people that Harley-Davidson doesn’t have a I monopoly on custom motorcycles,” says Cobra’s Denny Berg, the longI time customizer who transformed a stock Road Star 1600 into this stunner I of a Yama-chopper.

Working with Berg was designer Mike Rinaldi, a 25-year-old student at I California’s Art Center School of Design, an institution that counts among its alumni one Willie G. Davidson.

Rinaldi is a hot-rod freak, Berg’s a chopper builder from way back, so the decision to go with a stripped-down rigid was a no-brainer. Berg wanted to tie into the freewheeling feel of the 1970s chopper scene, to get away from the billet bolt-on “me-tooism” that afflicts so many of today’s catalog customs.

“It was an exciting time,” he says of the era. “People weren’t afraid to go outrageous; you couldn’t do anything wrong. There was some really wild stuff. You could chop a Royal Enfield or an Ariel Square 4, and people thought that was cool. The idea was to build something unique-there was not another one like it and there never would be. Now, that’s custom.” Engine choice was easy. In Berg’s words, a chopper needs “a lotta motor, a big lump, all engine.” The outsized V-Twin from Yamaha’s Road Star cruiser looked the part, plus it had the advantage of being air-cooled so there’d be no radiator, fan or coolant hoses to design around. “It looks like a motor,” says Berg. “Sure, it’s kinda Stone Age, it was meant to be that way, like an old aircraft engine.”

Rinaldi’s sketches called for the motor to be finished in various shades of bronze, playing off the metalflake-green frame and yellow bodywork. After being turned away by platers and anodizers, Berg took matters into his own hands, paid a visit to the local Home Depot and picked up several cans of Rustoleum spray paint in various bronze hues!

“People come up to me and say, ‘God, I bet that engine treatment cost a fortune,’ ” Berg says. “I don’t have the heart to tell ’em there’s maybe 15 bucks in it. Custom doesn’t have to mean expensive.”

That kind of ‘garage spirit,” as Berg calls it, permeated the building of LoStar. Much of the frame reworking was done with the engine bolted in place, for instance, though the front stretch and the projectorbeam headlights molded into the headstock go a little beyond Welding 101. Nor were any of Cobra’s bank of CNC cabinets fired up for this bike-most of the metalwork was done with a simple grinder.

“I wanted to keep the

shapes organic,” says Berg, pointing out the hand-done license-plate bracket. “There are too many perfect motorcycles out there these days. Look at nature, a rock, a tree-sure, they’re symmetric, but they’re not perfect.”

The front end is another example. When the aluminum rim was deemed too shiny, Berg got out his Brillo Pad and roughed things up. The stock hub-“a beautiful piece,” notes Berg-was retained, but with the flange for the right rotor machined off. In an interesting bit of parts-bin crosspollination, a six-piston FZR caliper bolts right up to the Road Star’s stanchion. The rotor is from Braking and was further hot-rodded by Berg, who didn’t like the ultra precision of its laser-cut vent holes and chamfered each one on his drill press.

“That extra dimension to the edges really made the rotors come alive,” he says.

Except for the exhausts and forward-mount footpegs (the only Cobra catalog parts on the bike), there is no chrome on Lo-Star. “That’s been done to death,” says Berg.

End result is a jaw-dropper unlike any other custom-meeting one of Berg’s carryover criteria from the Seventies. Centerstage is that rattle-canned engine, all fins and bulges and pushrod tubes. The nickelplated tiller handlebar pays homage to early Harleys, Indians and Excelsiors.

And there’s a hint of Norton Atlas in the gas tank’s stretched shape, arrived at after hours of turkey-carver surgery on styrofoam blocks.

So, what’s it like to ride this rigid retro? Not that bad, really. The fork, though radically shortened, puts up a pretty good first line of defense against bumps, and running the rear 190mm Pirelli at 20 psi helps, as does the wellpadded seat. It’s certainly no worse than some severely slammed Softails I’ve ridden, which have suspension in name only.

The image that sticks with me, though, occurred during Daytona Bike Week on a troll down Main Street. A well-lubricated biker-type breaks from the throng of gawkers on the sidewalk, runs up to Lo-Star and blurts out, “Wow! What is that, anyway?”

Upon learning the bike started life as a Yamaha, the man sneers, then backs away like the thing is radioactive.

As Berg says, “The ones who don’t get it are the ones who are missing out...”

David Edwards

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontNed's Sled

August 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsCharacter Infusion

August 2000 By Peter Egan -

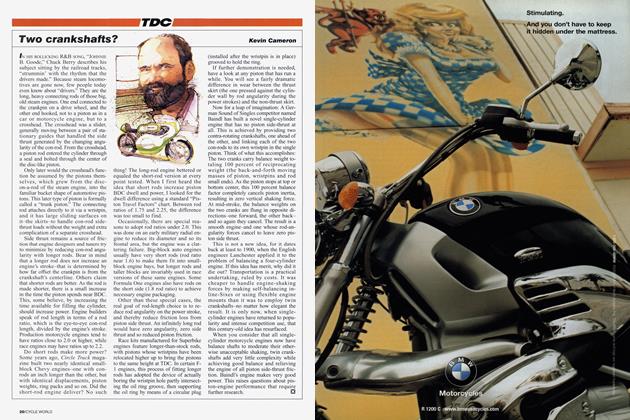

TDC

TDCTwo Crankshafts?

August 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupEurope Gets Naked!

August 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupIndian's Sporting Scout

August 2000 By Wendy F. Black