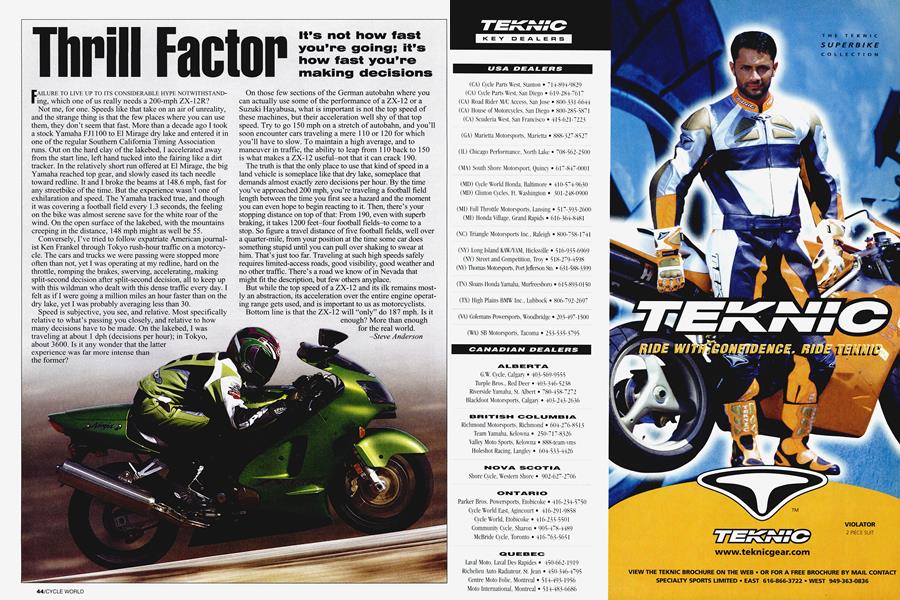

Thrill Factor

It’s not how fast you’re going; it’s how fast you’re making decisions

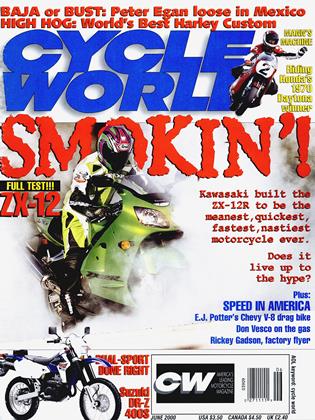

FAILURE TO LIVE UP TO ITS CONSIDERABLE HYPE NOTWITHSTANDing, which one of us really needs a 200-mph ZX-12R?

Not me, for one. Speeds like that take on an air of unreality, and the strange thing is that the few places where you can use them, they don’t seem that fast. More than a decade ago I took a stock Yamaha FJ1100 to El Mirage dry lake and entered it in one of the regular Southern California Timing Association runs. Out on the hard clay of the lakebed, I accelerated away from the start line, left hand tucked into the fairing like a dirt tracker. In the relatively short run offered at El Mirage, the big Yamaha reached top gear, and slowly eased its tach needle toward redline. It and I broke the beams at 148.6 mph, fast for any streetbike of the time. But the experience wasn’t one of exhilaration and speed. The Yamaha tracked true, and though it was covering a football field every 1.3 seconds, the feeling on the bike was almost serene save for the white roar of the wind. On the open surface of the lakebed, with the mountains creeping in the distance, 148 mph might as well be 55.

Conversely, I’ve tried to follow expatriate American journalist Ken Frankel through Tokyo rush-hour traffic on a motorcycle. The cars and trucks we were passing were stopped more often than not, yet I was operating at my redline, hard on the throttle, romping the brakes, swerving, accelerating, making split-second decision after split-second decision, all to keep up with this wildman who dealt with this dense traffic every day. I felt as if I were going a million miles an hour faster than on the dry lake, yet I was probably averaging less than 30.

Speed is subjective, you see, and relative. Most specifically relative to what’s passing you closely, and relative to how many decisions have to be made. On the lakebed, I was traveling at about 1 dph (decisions per hour); in Tokyo, about 3600. Is it any wonder that the latter experience was far more intense than the former?

On those few sections of the German autobahn where you can actually use some of the performance of a ZX-12 or a Suzuki Hayabusa, what is important is not the top speed of these machines, but their acceleration well shy of that top speed. Try to go 150 mph on a stretch of autobahn, and you’ll soon encounter cars traveling a mere 110 or 120 for which you’ll have to slow. To maintain a high average, and to maneuver in traffic, the ability to leap from 110 back to 150 is what makes a ZX-12 useful-not that it can crack 190.

The truth is that the only place to use that kind of speed in a land vehicle is someplace like that dry lake, someplace that demands almost exactly zero decisions per hour. By the time you’ve approached 200 mph, you’re traveling a football field length between the time you first see a hazard and the moment you can even hope to begin reacting to it. Then, there’s your stopping distance on top of that: From 190, even with superb braking, it takes 1200 feet-four football fields-to come to a stop. So figure a travel distance of five football fields, well over a quarter-mile, from your position at the time some car does something stupid until you can pull over shaking to swear at him. That’s just too far. Traveling at such high speeds safely requires limited-access roads, good visibility, good weather and no other traffic. There’s a road we know of in Nevada that might fit the description, but few others anyplace.

But while the top speed of a ZX-12 and its ilk remains mostly an abstraction, its acceleration over the entire engine operating range gets used, and is important to us as motorcyclists.

Bottom line is that the ZX-12 will “only” do 187 mph. Is it enough? More than enough for the real world.

Steve Anderson

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Great Clinton Land Grab

June 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOuter Daytona

June 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWays And Means

June 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2000 -

Roundup

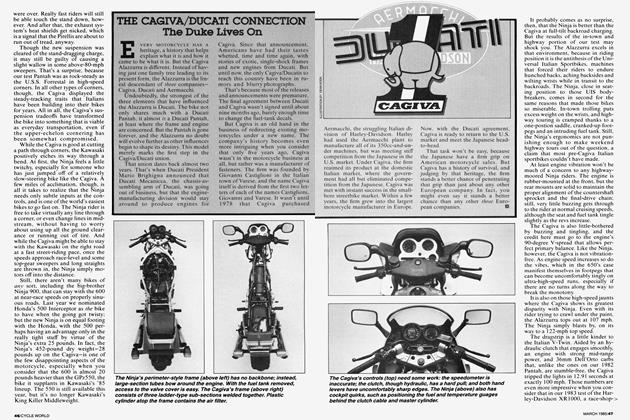

RoundupV-Twin Attack! Ktm Targets Japan Inc.

June 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupRoost In Peace, Joe Motocross

June 2000 By Wendy F. Black