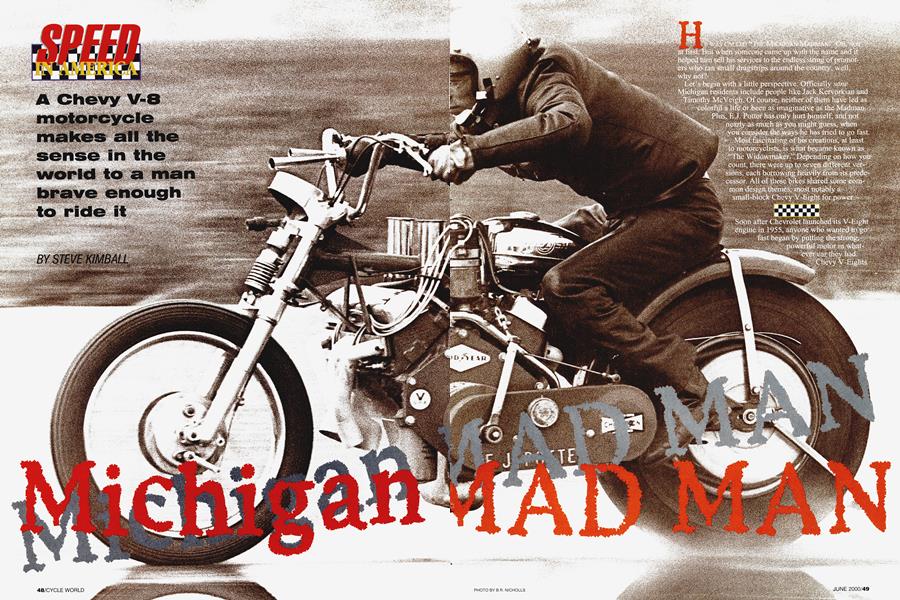

Michigan MAD MAN

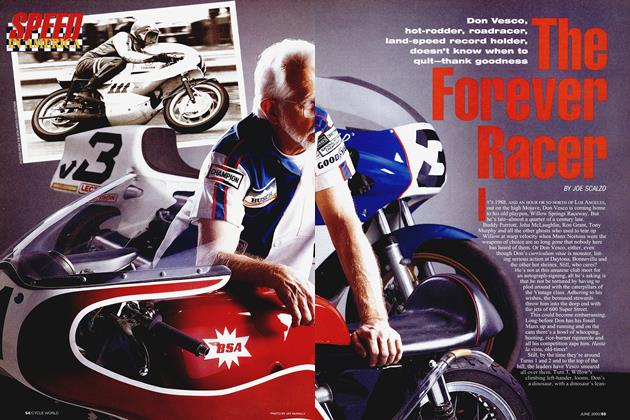

SPEED IN AMERICA

A Chevy V-8 motorcycle makes all the sence in the world to a man brave enough to ride it

STEVE KIMBALL

HE WAS CALLED THE MICHIGAN MADMAN." OH NOT at first. But when someone came up with name and it helped him sell his services to the endless string of promorers who ran small dragsrips around the country, well, why not?

Let's begin with little perspective. Officially sane Michigan residents include people like Jack Kervorian and Timothy MCVeigh. Of course, neither of them have led as colorful a life or been as imaginative as the Madman.

were the engine of choice for hot-rods and fit just fine in ’32 Fords. The engine was compact enough to shoehorn into a variety of small sports cars, which became the stuff of legend and numerous magazine stories.

E.J. Potter wasn’t yet in high school when the Chevy VEight came out. Still, he was already fooling around with motorbikes in the small central Michigan town of Ithica. Something about central Michigan (look up Scott Parker,

Jay Springsteen and Bart Markel) makes people want to ride bikes around in circles, and Potter did enough of this in his youth to learn that the rear wheel of a motorcycle doesn’t necessarily have to follow the front, and that traction isn’t always essential to going places.

We’ll get to this later in our story.

Eventually, the ingenious Potter put a tape measure to a Chevy motor and also to a HarleyDavidson 74, and discovered that the V-Eight was about the same height and width as the Harley V-Twin, but of course noticeably deeper. It took a

little cash earned working at the local gas station, a welding torch, an old Knucklehead frame and a junkyard Chevy 283 cubic incher before he could get into the details of engineering.

“Ready, fire, aim,” is how Potter describes his design process.

Gaze upon our picture of a youthful E.J. on his first V-Eight motorcycle, circa 1960, parked in front of a tractor and a ’58 Ford. A Whizzer gas tank is perched high in the air. It feeds a pair of carburetors bolted to a homemade intake manifold needed to fit around the Harley’s frame. The exhaust bolts into square tube, welded to the frame downtubes. Except for some bar stock welded to the front of the frame, it’s a stock Harley chassis, right down to the springer fork and miniscule front brake.

Pay attention to what you don’t see. There’s no radiator. No electrical system to speak of. No starter. Leave off enough stuff and the weight comes down to 750 pounds, including rider weight, Potter says. The transmission amounts to a #50 chain connecting the engine to a homemade centrifugal clutch built out of a Harley brake drum,

which was connected to the large rear sprocket with more chain. Overall gear ratio was about 3:1, Potter recalls.

This monumentally simple motorcycle not only ran, but was such a curiosity that Potter was invited to run it at a local dragstrip. His initial pass resulted in nothing more than a broken rear sprocket and some advice from one of the other drag racers in attendance that day. The man told E.J. it looked like he could make some money with his V-Eight

creation, and

when Potter discovered the advice came from Art Arfons, driver and creator of the legendary Green Monster airplaneengined crowdpleaser, a career was born.

With the promise of being paid $1 for each mile per hour he exceeded 100 mph, Potter began learning how to milk the bike for speed, and how to work with promoters-both essential ingredi-

ents for anyone who wants to get paid for going fast.

Before his first summer of exhibition drag racing

was done, Potter made another giant leap in technology. The homemade clutch had been spotty at best. It slipped and it broke. That, Potter decided, would forever limit his maximum trap speed to about 115 mph, which also meant his income was limited to $15 per race. The obvious solution-to a person sick enough to seek a solution-was to eliminate the clutch altogether. It occurred to Potter that he could put the bike on a rear propstand, start the engine, then push the bike off the stand and let the rear tire spin until bike speed caught up with rear-tire speed. In effect, he let the rear tire do double-duty as a clutch. Genius!

Any of you who want to try this at home, be forewarned:

A motorcycle dropped on a spinning rear tire does not want to go straight forward. It wants to veer to one side or the other, depending on the track and other factors. The discovery of this principle is a lot more exciting in the laboratory of the dragstrip, where gravel, dropped oil and crash fences make for a steep-make that vertical-learning curve.

With a little practice, though, Potter learned how to launch his Chevy motorcycle, let it weave its way down the dragstrip, and control it just enough to avoid hurting himself seriously. Most of the time.

Instantly, the V-Eight was returning trap speeds up to 136 mph, which was enough to make the promoter want to renegotiate: “How about a buck for every mph over 120?”

With a summer of knowledge built up, Potter began bike number two. Inspiration came from a found intake manifold holding four carburetors. During bike number one’s disassembly process, which involved cutting the engine out of the frame, Potter discovered that one of the Harley’s downtubes had been broken for a long time. Deciding he could do better, Potter welded up a new mild-steel frame, this one abandoning downtubes and full-cradle design. Instead, it had a large tubular backbone and a trellis structure using the engine as a stressed member. Onto this he hung an IndianEnfield telescopic fork, equipped with a larger drum brake. This was also the time to discover the pleasures of mixing fuel, using parts alcohol, ether and benzene.

Over the next dozen years. Potter kept on adding power. The first engine was a stock 180bhp Chevrolet. The second bike was much faster with its four carburetors and fuel cocktail. Later, Potter went to 327-cube engines and eventually tried versions as large as 350 inches. Power on the last versions may have been as high as 600 bhp, Potter speculates.

Other mod-cons included the adaptation of a fat car slick and fuel injection. All the Widowmakers remained no longer than 8 feet. That way they fit in the back of a pickup. Drag racing for money did not involve a transporter or a crew for Potter.

That instant of dropping a rear tire spinning at up to 225 mph onto pavement may appear to be the most demanding part of riding the Widowmaker, but Potter insists that was the easy part.

“It was real smooth when you dropped it off the jack,” he says. “There wasn’t any lunge out of the gate.”

There was, however, tire smoke-great roiling plumes of it. Not to forget the aforementioned sideways action.

“That’s what I was getting paid for anyway,” he says. “In order to be worth money to a promoter, people have to think you almost got killed. That way, they buy a ticket next time.”

At some point in the brief ride down the strip, bike speed caught up with rear-tire speed, but the fun wasn’t over. “If you hit some bumps, then the front end might come up in the air. You don’t have much time to get it down,” Potter says. When the front end did lift, a hard landing usually followed. “It wanted to go into tank-slappers. Then, it’s a matter of holding on until the speed drops under about 100, when the wobble stops.”

As ugly as this sounds, Potter says the hardest part came after the finish line.

Remember that small HarleyDavidson front brake on the original bike? That’s why the next year he had a full-width drum from a 700cc Indian. And later models went to disc brakes.

Potter’s V-Eight was a thrill to ride, but it was also a business.

“I made a living at it ’cause I didn’t spend anything,” he relates. “That first bike cost probably around $500. The last one, I still only had maybe $3000 in it. That’s with the engine and everything.

Today, you can’t

get a set of heads for $3000,” he adds.

Potter was a showman. He learned how to make and ride a machine that terrified and excited people who came to racetracks. That meant learning how to deal with promoters, which wasn’t always easy. Over the years, that meant riding at tracks with bumps, or without lights, or with barbed-wire fences across the runoff areas. A racer had to live to collect his payment, but that was of more concern to the racer than the promoter.

After 1973, the Chevy motorcycle was sold. Potter developed other ways to excite and entertain people. He put a jet engine in a trike. He made an electric drag racer that could hit 120 mph through the traps. He put WWII airplane engines in tractors used for pulling contests. The ideas sprouted up like weeds beside his bam in Michigan. Potter made them all work.

Today, E.J. is retired. “I’m not sure what I’m retired from,” he says, but he calls himself a geezer living in Florida. He travels (Costa Rica is a favorite destination) and he still has a farm in Michigan to visit in the summer.

Potter is not done riding motorcycles, not even the VEight. A couple of years ago, Widowmaker Seven, restored and on display in the Don Garlits museum in Florida, was trucked to a

dragstrip. At the age of 57, a survivor of several broken bones and racing scrapes, Potter donned a new set of black leathers, fired up the bike one more time and let fly.

“I felt like I was 2 years old again,” he says of the adventure.

The biggest surprise to him was the condition of the racetrack. “I found out that they use traction compound now,” laments Potter. “It feels like walking on flypaper. But as soon as you spin the tire, that stuff turns to oil. So I was skating

all over the place. Only ran 151 something, not quite 152.” Back in the day, Potter had seen 176 mph.

There could be more exhibitions. Potter is thinking of taking the bike to Australia again, where he hopes the tracks are more conducive to high speeds. More than 30 years ago, his 8.68-second run Down Under was listed in the Guinness Book of World Records.

But he could also get involved in a jetboat project, or turbine-powerplant operation.

“For the past 40 years, I’ve never

known what 1 was going to do the next couple of days ahead, really. I’m still that way,” the Michigan Madman says.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontThe Great Clinton Land Grab

June 2000 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsOuter Daytona

June 2000 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCWays And Means

June 2000 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

June 2000 -

Roundup

RoundupV-Twin Attack! Ktm Targets Japan Inc.

June 2000 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupRoost In Peace, Joe Motocross

June 2000 By Wendy F. Black