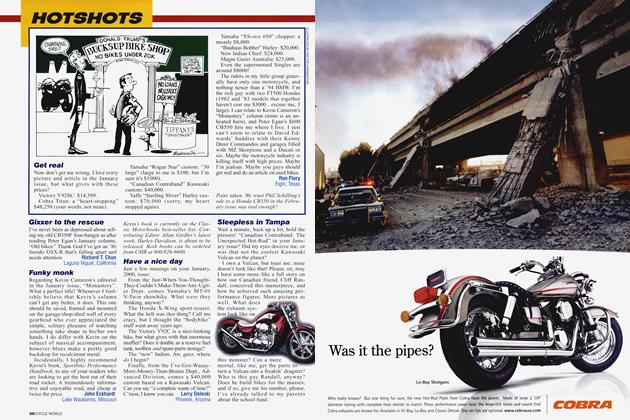

Lost & Found

Uncovering Fonzie's forgotten Triumph

WENDY F.BLACK

THE YEAR WAS 1975,BUT THE SETTING was smack-dab mid-Fifties. The charismatic Arthur Fonzarelli, resplendent in white leather for once, prepared to jump his silver Triumph over 14 garbage cans in the parking lot of local hangout Arnold’s. He cleared the chasm, though he dumped the bike in the process. Nonetheless, millions of kids all over the country—me included—cheered his victory.

For an entire generation of post-babyboomers, leather-clad Fonzie and his motorcycle embodied everything cool. He was the guy all the boys wanted to be; the man all the girls just plain wanted. And the bike, well, it was clearly an homage to the original Cool One-James Dean, u whose likeness peered down laconically from a poster tacked to The Fonz’s Afe. closet door.

Brought to life by actor Henry Winkler, Fonzie (with his trademark “Aaavvy! ”) was a main character on the television series “Happy Days,” which aired Tuesday nights at 8 p.m. from 1974 through 1984. According to the Nielsen ratings, during the show’s peak season in 1977 it was turned on in 23 million homes and watched by close to 40 million people.

” ’Happy Days' is one of the landmark shows in TV history,” says Tim Brooks, former network executive and co-author of The Complete Directory to Prime Time Network and Cable TV Shows. “It came along when TV was dominated by shows growing out of the unrest from the Vietnam War period. Shows with real social bite, like ‘All in the Family,’ ‘Maude’ and ‘Sanford and Son.’ Heavy and sometimes preachy shows. ‘Happy Days’ dealt with simpler times and a more reassuring world. Not only was it a hit, it moved ABC from the number-three to the number-one network.

It changed the whole tenor of programming on television.”

While the tremendous success of “Happy Days” can’t be attributed solely to Fonzie and his bike, they were most certainly key. Originally, however, the character was supposed to be a fringe player only. In the first episode, for example, Winkler had just six lines. But as the show grew, thus did Fonzie evolve.

Explains Brooks,

“Winkler made The Fonz three-dimensional. He was always super-cool and superhip, but he had his vulnerable side and that made him a very appealing character.

Over the run of the show, he moved up in the cast listings moved up in the cast listings from seventh to third and then second, right after Ron Howard. Then when Ron left, Fonzie was the star. So he became an icon not just of the show, but of the 1970s and 1980s.”

All icons, of course, have accoutrements. Fonzie’s brown leather bomber jacket hangs in the Smithsonian Institute. But where was his trusty silver steed? No one seemed to know. So, I set out to find The Fonz’s longlost ride. I knew I was searching for a Triumph.

What I didn’t know was that I sought more than one.

Turns out there were actually four motorcycles belonging to His Fonzness, so says Desert Racer/Stuntman/ Hollywood Bike Provider Bud Ekins.

Bud

The first of Fonzie’s bikes belonged to one of Ekins’ cronies. It was not a Triumph at all, but a Harley-Davidson Knucklehead outfitted with a Sportster tank. Ekins claims this was used in just one episode. “The Harley was too big and too clumsy,” he recalls, “and Winkler didn’t know how to ride. So they

were pushing him in and out of the set, and they wanted something as small as possible.”

Hey.. .wait a minute! Winkler didn’t ride? What about the opening sequence of “Happy Days”? You know, where he cruises nonchalantly past fictitious Jefferson High? Apparently, that was his only saddle time. In a recent internet chat, Winkler was asked whether he rides. His disillusioning response: “I don’t know how to ride a motorcycle. I am scared to DEATH of motorcycles. That’s how good an actor I am. Do not let me near your motorcycle. Without a doubt, I will destroy it. If there is a wall, I will hit it.” Disappointing, yes. But not wholly unexpected, considering that Hollywood is all about suspended disbelief. Still, Winkler’s real-life lack of riding prowess diminishes the bike’s import not a whit. Because it was Fonzie (not Winkler) who was the biker with the heart of gold, the unwitting philosopher of the show.

Hypothesizes Brooks, “To some extent, he repopularized motorcycles. Up until then, motorcycles were a rough side of life. Through movies, they took on a more sinister aspect. The Fonz with his motorcycle was a safe rebel. The motorcycle was clearly part of his persona-it gave him that edge-but his dimensionality helped soften what a motorcycle was.”

My search for Fonzie’s bike continued. Because the original Harley was used only briefly and then discarded, three bikes remained unaccounted for. They all were Triumphs. The first was an early-’5 Os Trophy that Paramount borrowed for just a few shots, then returned to Ekins. He sold it through his dealership, and it later disappeared after being purchased by a now-defunct auction house. The second Triumph, the studio acquired from someone other than Ekins. It, unfortunately, was placed in storage and then allegedly stolen by an errant employee.

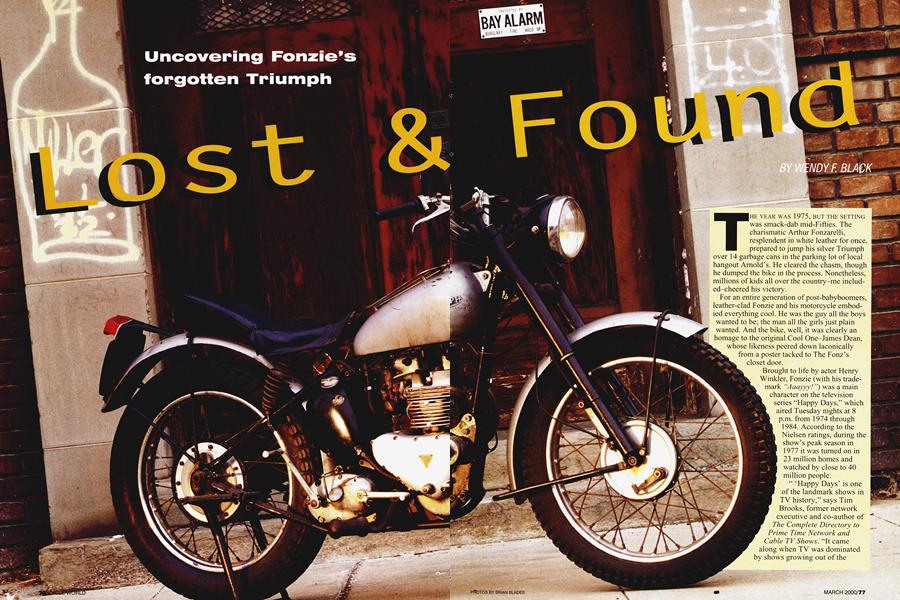

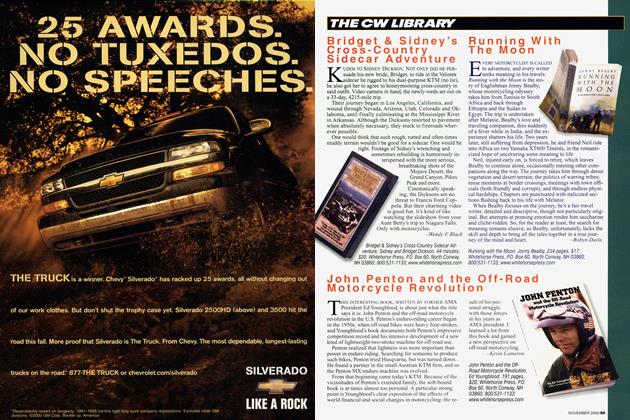

The third Triumph in question is the Trophy pictured here. Ekins is unsure as to whether it’s a 1949 or ’50 model, but either way it’s descended from the Tiger 100 that won the 1946 Manx Grand Prix at the Isle of Man.

That Tiger was the prototype for Triumph’s first official racebike since the mid-1930s. The factory christened this new model, naturally, the Grand Prix in 1948. In production for only three years, it was powered by a square-barrel alloy (as opposed to iron) engine borrowed from the aircraft generators Triumph built for the Royal Air Force during WWII.

This “Generator Set” engine also powered the Trophy, which debuted in 1949 and was intended for ISDT and trials competition. The ex-RAF motor had a short half-life, though, as Triumph changed the Trophy’s cylinder design in 1951. Because Triumph top man Edward Turner was distrusting of the “swinging arm” rear suspensions just coming into vogue, the Trophy used a rigid frame with an internally sprung rear hub to ward off bumps-an interesting if ill-fated approach.

Such history was irrelevant to Ekins, who was simply trying to provide Paramount Studios with a Triumph. After several years of playing Musical Trophies, this one was eventually cast off by the studio and Ekins sold it to a motorcycle dealer friend. Which explains how I came to be standing in Mean Marshall’s Motorcycles in Oakland, California, some 15 years later.

Revealing its owner’s tendencies toward things antique, the shop’s pegboard walls are decorated with handlebars from various Triumphs, Nortons and BSAs. Vintage service manuals, period posters and Triumph engine illustrations are everywhere. Glass display cases hold historic artifacts and accessories.

Behind the counter, aisles of shelving are home to dusty NOS parts-carburetors, Lucas military components, saddles, even frames still wrapped and packed in original shipping crates. Out back, ancient motor> cycles are queued up under tarp and canvas. Looking further reveals the boat yard, full of wooden Chris Craft models in various states of disrepair. All together, the establishment encompasses a total of almost 70,000 square feet.

Motorcycles remain at the forefront, though, hence the name of the place. Originally from Chicago, Mean Marshall Ehlers has been in Oakland since 1972. Although he deals in vintage bikes, he’s not what you’d call a restorer (nor is he all that mean). He’s more of a mechanic/vintage supplier (and just a wee bit on the gruff side). He’s an incurable collector of motorcycles past, and his assortment is immense.

The “Happy Days” bike he bought not for its star quality, but rather for its racing cred. “This was Triumph’s very first win at Daytona in 1950. It was ridden by the late Rod Coates,” says Ehlers, referring more to the alloy engine than the bike itself, as Coates won Daytona’s 100-mile Amateur Championship aboard an aforementioned Grand Prix. “Most of these bikes were bought during the ’50s by racers, and were crashed or exploded. When I saw one intact, I bought it. It had nothing to do with television.”

Yet it’s television to which this particular bike owes its mainstream popularity. Currently,

Fonzie’s Triumph sits forlornly in Ehlers’ shop. It rests on the concrete floor of what could be called a showroom only in the most optimistic of terms.

Languishing between a BSA B50 and a late-model Bonneville, the sad little Trophy hasn’t been worked on, let alone restored.

We removed the “Do Not Touch” sign from the handlebar, and ran a shop rag over the dented, scratched-up tank and its nifty little parcel rack. The steel-tube frame,

too, was wiped free of excess dust, as was the funky headlamp nacelle. Of course, there were some things we just couldn’t touch up: the rusty seat springs, the dried oil embedded into the crankcase pores, the crunched battery

holder. It probably goes without saying that this Trophy isn’t a runner. Never was, actually. Ekins claims he started it. Once. But since its purpose was to be pushed into and out of scenes, its lack of life wasn’t a problem.

Overall, the bike needs some love. Perhaps Ehlers would be willing to sell it to some interested third party intrigued by its glitzy past? As if! It seems that Planet Hollywood has offered him “absurd sums of money” for the machine, but Ehlers ain’t sellin’. He prefers to hold onto the bike and give it to, say, his children someday.

Confides mechanic and friend John Rios, “I honestly believe Marshall would rather give this bike to a museum for free than sell it to Planet Hollywood.”

! So what’s in store for the bike that once looked so cool parked outside of Arnold’s with Fonzie leaning confidently against the leather saddle while the tightly sweatered Paula Petralunga draped herself over I him? Ehlers is vague.

He won’t discuss money. Period. He ponders

restoring the bike to original spec, TV history be damned, or possibly installing a genuine Triumph hop-up racing kit. He has one, of course. It’s sitting on a nearby shelf.

For now, Mean Marshall is content to let the bike grace his shop until he figures out a plan. For those “Happy Days” fans who are unsatisfied or disappointed with this turn of events-well, tough. The bike is his, and he’ll do with it as he pleases.

Hey, The Fonz would understand.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue