Return to Monza

POWER PACKED SECTION

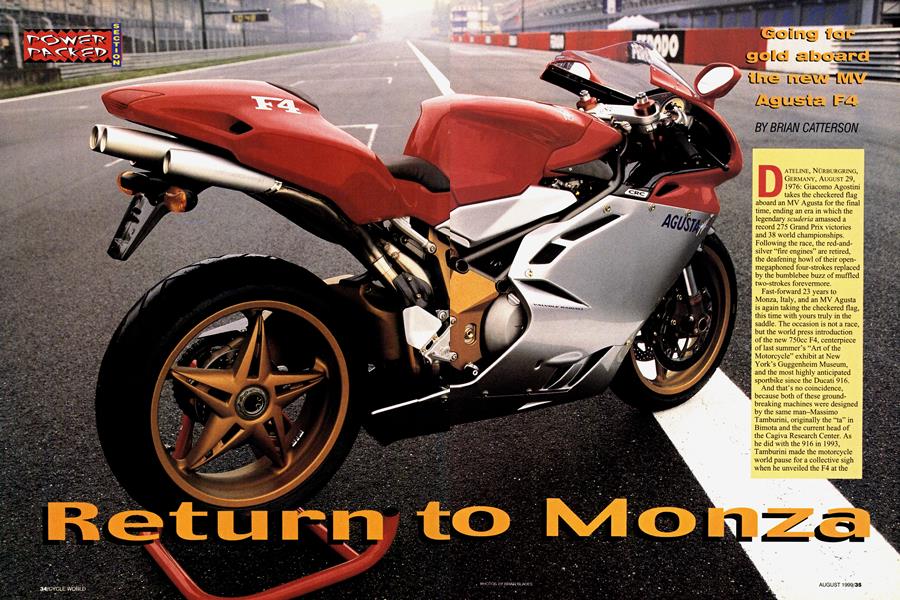

Going for gold aboard the new MV Agusta F4

BRIAN CATTERSON

DATELINE, NÜRBURGRING, GERMANY, AUGUST 29, 1976: Giacomo Agostini takes the checkered flag aboard an MV Agusta for the final time, ending an era in which the legendary scuderia amassed a record 275 Grand Prix victories and 38 world championships. Following the race, the red-andsilver “fire engines” are retired, the deafening howl of their openmegaphoned four-strokes replaced by the bumblebee buzz of muffled two-strokes forevermore.

Fast-forward 23 years to Monza, Italy, and an MV Agusta is again taking the checkered flag, this time with yours truly in the saddle. The occasion is not a race, but the world press introduction of the new 750cc F4, centerpiece of last summer’s “Art of the Motorcycle” exhibit at New York’s Guggenheim Museum, and the most highly anticipated sportbike since the Ducati 916.

And that’s no coincidence, because both of these groundbreaking machines were designed by the same man-Massimo Tamburini, originally the “ta” in Bimota and the current head of the Cagiva Research Center. As he did with the 916 in 1993, Tamburini made the motorcycle world pause for a collective sigh when he unveiled the F4 at the 1997 Milan Show. Truly, photographs do not do this bike justice; it must be seen in three dimensions

to be appreciated.

For an italophile like me, riding an MV Agusta at the fabled Autódromo di Monza was the stuff of dreams. But for Cagiva boss Claudio Castiglioni, watching the red-and-silver machines in motion was the triumphant realization of a lifelong aspiration.

“When I was a child, 8 years old, my father took me to watch Agostini race at Monza,” he said. “It made a lasting impression on me, which is why the Cagiva Grand Prix racers were painted in the same colors. Now that I am chairman of MV Agusta, my goal is to have the brand known like it was before.”

The bikes the press was invited to ride were the first of the Serie Oro (“Gold Series”) models, handmade, limited-production, $36,995 rolling objets d’art that represent the first phase of MV’s twophased return. The second will be the F4 S (for Strada, or “Street”), available this fall in greater numbers for $18,900.

What’s the difference? Details. The Oro’s name alludes to its liberal use of gold-colored magnesium-the intricate single-sided swingarm, the pivot plates, the lower triple-clamp and the starshaped wheels all are cast in the precious metal. Moreover, the Oro’s aluminum engine is sand-cast, in best MV tradition, and its bodywork is carbonfiber. The S will make do with aluminum chassis pieces, a die-cast engine and plastic bodywork. But everything else is identical, right down to the claimed 126 horsepower and 406-pound dry weight (the S’s lighter die-cast engine is said to offset its heavier chassis parts).

At the technical presentation the evening prior to our test ride, many of the F4’s pieces were laid out on a table, where journalists were invited to examine them up close. Eyeballing the massive, six-bolt lower triple-clamp and steering stem, I thought it would make an impressive door stop, until lifting it revealed that it wouldn’t be nearly heavy enough! The carbon-fiber fuel tank similarly defied gravity. In fact, the only item on display that had any heft was the steel-trellis upper portion of the composite frame. And undoubtedly the engine, though I didn’t try to lift that.

I did look at it though, and noticed some interesting details. At first glance, the engine appears quite conventional. The cylinder block is cast as a separate entity, not as part of the cases or, as in cutting-edge Formula One practice, the head. And the camchain is located in its traditional spot between the number 2 and 3 cylinders. Many engineers abandoned this practice long ago, preferring to relocate the cam drive to one end of the crank and eliminate a journal in the process, but F4 engine designer Andrea Goggi-himself a Cagiva 500cc GP team alumnus-insists that the traditional layout was essential in achieving the necessary rigidity for employing the engine as a stressed member of the frame.

Looking closer revealed a few departures from the norm. For one, where the heat exchanger and oil filter on many liquid-cooled engines are mounted one atop the other, the MV’s are positioned side by side. In conjunction with a curved radiator and a flow exchanger that routes heated air down toward the ground, this allows the engine to be positioned as far forward as possible for optimal weight distribution (52 percent front/48 percent rear) without fear of engine/tire contact. Similar measures were taken to reduce engine width; the starter motor and alternator reside next to one another atop the shrink-wrapped crankcases.

Standing beside U.S. importer Larry Ferracci, I noted the elongated bosses where the cylinder head joins the frame. Why all the extra metal? Ferracci looked both ways, then hushedly intimated that this will allow

greater flexibility for future models. Rumor holds that the company is developing a bored-and-stroked, 900cc variant for use in the projected Brutale naked bike.

More puzzling was the camchain tensioner’s location on the front of the cylinder block. Why there instead of in its traditional spot at the rear? The following day at the racetrack, Goggi explained why this was so. Grabbing a reporter’s notebook, he quickly sketched the engine’s cam-drive layout, which appeared quite ordinary-with one exception: A reduction gear driven off the crankshaft lets the cams spin at the required half crank speed without resorting to oversized cam sprockets, effectively reducing the size of the cambox. A sideeffect is that the cams spin backwards, thus the unorthodox location of the tensioner.

But the engine’s most notable technical feature remains its use of radial-valve combustion chambers, as trumpeted by the Valvole Radiali decals adorning the bike’s flanks. While radial valves are nothing new (Honda Singles have had them for years), the F4 marks the first time the system has been used on a production Multi, or for that matter with direct valve actuation instead of rocker arms. With a 22-degree included valve angle, and each valve further angled 2 degrees radially, the compact combustion chamber is in effect tent-shaped. But according to Goggi, the main advantage isn’t the shape, but the simple fact that when a valve opens, there is more space between its head and the adjoining cylinder wall, and more space means greater flow. To work with the radial valves, each cam lobe is ground at a 2-degree angle; so slight is the bevel that you’d never detect it unless you knew it was there.

Goggi also took time to dispel myths surrounding Ferrari’s involvement in the F4 project. Yes, he admitted, Ferrari did the original design work on the engine in 1990, but very few of those contributions remain. Early on, there was talk of an ultra-narrow V-angle, as pioneered on Lancia automobiles in the 1920s and currently employed on Volkswagen’s VR6, but this ultimately was rejected. Goggi agrees that such a layout would allow closer bore centers, but given the F4’s small cylinders (73.8 x 43.8mm), he doesn’t feel the gain would be worth the added complexity in the manufacturing process. As it is, the F4’s inline engine is said to be 2 inches narrower than that of a Suzuki GSX-R750.

Watching photographers swarm over the two F4s parked on Monza’s pit straight, it was impossible not to be captivated by the bikes’ forms. From the stacked polyellipsoidal headlights to the quad exhaust tucked, 916-like, under the seat, the F4’s styling is a breath of fresh air. Everywhere you look, there are trick details. As on a 916, the F4’s steering-head angle is adjustable, though you first have to purchase parts from the forthcoming race kit. And even better than a 916, the F4’s swingarm-pivot location is adjustable, again with race-kit parts. Hinged “bracelet” clamps on the clip-on handlebars and the front brake and clutch master cylinders expedite fork servicing or crash repairs, while drop-away axle clamps on the fork and a solitary axle nut on the single-sided swingarm speed tire changes. The Showa fork, Sachs shock and crossways Öhlins steering damper are fully adjustable, a variable-length linkage rod allows easy ride-height adjustments, and an alternate pivot point on the shock rocker changes the leverage ratio. Even the footpegs and foot controls are tunable, their locations changeable via eccentrics. And let’s not forget the cassette-style six-speed transmission, designed to ease internal gear-ratio changes at the racetrack; the MV is the first production fourstroke to be so equipped.

With rain having bumped the preceding day’s journalists to “our” day, time on the bikes was brief; I got just two halfhour sessions, or about 20 laps total. And Monza is not an easy track to learn. Built in a forested park that once served as a nobleman’s private hunting grounds, the 3.5-mile circuit is overhung by trees and surrounded by guardrails, so the turns are all blind. Runoff is nil, but it’s better since the installation of three chicanes, or variantes, designed to slow speeds through the faster-and thus more dangerous-comers. When Ago & Co. raced here, it was flat-out. And lethal:

One infamous accident in the 1973 Italian GP claimed the lives of both Jamo Saarinen and Renzo Pasolini, two top racers of the day.

Straddling the F4 in the Monza pits, I tried to put the danger out of my mind and focus on more pertinent matters-such as how small the bike feels. The close-coupled riding position is very much like that of a Yamaha YZF-R1, purposeful and tight, yet not at all cramped. And it’s extremely slim-. 8-inch narrower than a 916 at its widest point, if you believe the hype. Not bad for an inline-Four...

Turning the ignition key brings the electronic instmment panel to life, the needle on the yellow-faced tach swinging up to the 17,000-rpm limit before returning to zero. As on current Ducatis, the MV’s tach has no redline per se; there is, however, a shift light programmed to illuminate at 12,500 rpm, though the rev limiter doesn’t cut in until 13,300.

Hunting for the choke lever, I found it in an unconventional location adjacent to the twistgrip. And again, it was anything but ordinary, a dial perhaps an inch across with a tiny crank arm like that of an organ grinder. Choke activated, I pushed the starter button and the engine fired immediately, settling into a typical four-cylinder idle. Listening to the F4s speeding down the pit straight earlier in the day, I’d been disappointed by the GSX-R-like sound. But sitting in the saddle, the engine seemed much more menacing, multitudinous mechanical noises reverberating up from the carbon-fiber fairing lowers to fill my helmet.

Squeezing the clutch lever provided another visceral surprise, as the pull is very light-the absolute antithesis of Ducati’s bane. The range of engagement is quite narrow, however, so you need to take care in letting out the lever or risk stalling the engine. But otherwise, there’s never any fear of bogging, as the ram-air-fed engine makes good, usable power from just above idle to the 12,200-rpm peak. Power delivery is linear and ultra-smooth, thanks both to the precise mapping of the Magnetti Marelli fuel-injection system and the relatively heavy crank.

That heavy crank contributes to the engine’s slightly slow-revving nature, and this undoubtedly played a role in my original suspicion that perhaps the F4 wasn’t that fast. And while the 276 kph (166 mph) indicated by the digital speedo on Monza’s long front straight hinted otherwise, it wasn’t until I rode the F4 on the street the next day that I was convinced: This thing is a missile!

Better yet, it’s a self-guided missile. Suspension and handling are impeccable, better than anything Eve sampled this side of a race-prepped Superbike. More so even than a 916, the F4 manages that rare combination of rock-solid stability and steering ease. I appreciated the former while railing through the Armco-lined, fifth-gear Curvone, and the latter while tossing the bike back and forth through the three chi-

canes. The only time I experienced any headshake was when I got on the gas too hard while transitioning through the Variante Della Roggia, and the front Pirelli Dragon Evo tire got light and did a little dance as it skimmed the tarmac. Oh well, that's what the outside curbs are for!

I also had a few “moments” while braking for the aforementioned variante, as a bump hidden in the shadow of a bridge bottomed the fork and encouraged the rear end to pass the front on a number of occasions. But while the fork springs might be a tad too soft, there’s absolutely nothing wrong with the brakes. Up front, the twin Nissin six-piston calipers acting on 310mm floating steel rotors are powerful without being grabby, while out back, the single four-piston caliper mated to a 210mm disc is barely strong enough to

skid the tire-or in other words, perfect for a sportbike.

Climbing off the MV at the end of the day, the only aspects of the bike that I could fault were the typically pathetic mirrors and self-retracting kickstand, and the gearbox action, which is notchier than that of the MV’s Japanese contemporaries. But even so,

I never missed a shift-well, except for the shift to neutral, which proved frustrating at a standstill.

Better to click down from second while you’re still rolling.

That

evening, we drove to

Varese, home of Cagiva’s two factories, which we had been invited to tour the next day.

There, we stayed in the Palace Hotel, where Carl Fogarty’s 916 and Eddie Lawson’s Cagiva 500 are displayed in the lobby, and the complimentary shampoo bottles bear the Cagiva Group’s logo. We dined at Claudio Castiglioni’s home, discussing such important topics as the state of the U.S. motorcycle market, MV’s place in history and Cagiva’s future Predictably, talk turned to racing, specifically the proposed switch to four-strokes in GPs and how this might affect MV’s future racing plans.

Castiglioni is, of course, chomping at the bit to go racing; Í'ÍHMI remember, this is the man ff who dared to take on the Æ Japanese in the Æ 500cc GPs and L Jm World Superbike S** «7 won. /J ¿fj Í. I t ArSHBfsk.

But his company’s recent financial woes have tempered his enthusiasm, and he has sworn off competition until the 2001 season.

For the moment at least, he realizes that commercial considerations must come before racing frivolities. Still, it was impossible not to see the gleam in his eye as he confirmed that, ultimately, he would like to compete not in World Superbike, but the GPs. where the MV Agusta name is legendary.

Hmmm...the last four-stroke to win a GP, and the first to win again? Now that áíll) would tk make for a m storybook m . ; ^ ending! JL

-..W There’s just ÉÊÊÊStËr one problem: As Castiglioni said. “We . must win our first time LU^^PF out.” * “Why’s that?” I wondered aloud. Castiglioni smiled knowingly and replied, Because MV never loses.” I

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

Up FrontGo Show

August 1999 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsMotorcyclist's Calendar

August 1999 By Peter Egan -

TDC

TDCBackmen

August 1999 By Kevin Cameron -

Departments

DepartmentsHotshots

August 1999 -

Roundup

RoundupCagiva's Monster Musclebike

August 1999 By Matthew Miles -

Roundup

RoundupBuell's Total Recall

August 1999 By David Edwards