Speaking Softly

Yamaha's big sticks

DURING MOST OF THE 1970S, IT APPEARED that Honda was switching to the car market and de-emphasizing motorcycles. First the Civic and then the Accord autos achieved major success. On the motorcycle side, the models were unexciting if reliable. Could Honda be giving up its two-wheeled business in favor of four? Yamaha planners saw an invitation to reach for the top spot.

We know what happened next. Honda responded in force, did its homework, threw back the challenge with a flood of new engineering. In the end, Honda retained its lead and then reinforced it.

Yamaha long had a strong position in Grand Prix and U.S. roadracing. TZs and YZRs were the gold standard, making Honda look like an inexperienced outsider-until Honda bore down hard in the 1980s, becoming dominant in GP racing after 1992.

Here in the West, we must remind ourselves of how little we understand Japanese culture, and how little our models of behavior may apply to it. Here, if Ford sells more cars than GM, then it is number one and GM becomes number two. In Japan, corporate status may have more than a dollars-and-cents basis. Here, we see a company-to-company duel as being like a prize fight-let the better man win. In Japan, all companies are tightly interrelated through banking and trading houses. Durable relationships are established. Why has Suzuki put up with so many winless years in Superbike racing-especially when they have fielded strong designs? Maybe because, to at least some degree, each Japanese company makes an effort in sales, in racing, in design, that is appropriate to its position in the established pecking order. I don’t know if this is accurate, but it could explain a lot.

In this view, Yamaha’s late-1970s attempt to take over the top position from Honda was not just aggressive business strategy-it was antisocial, somehow improper.

Now, things are happening again. The Japanese economy gambled big on real estate values through the 1980s. And lost big. Now the country is paying the price with a nogrowth economy and an unheard of 4-5 percent unemployment rate. This is considered healthy by business-oriented experts here, but in Japan, unemployment like this hasn’t happened since the war. After Japan’s high-riding ascent to the number-two position among world economies, this setback has hit hard.

Worldwide, there is too much automotive production capacity for existing markets to support. The result is mergers like the Daimler-Chrysler deal or buy-ins like Renault’s taking a 37 percent share in teetering Nissan. Japan’s stalled economy makes this problem especially acute over there-including the motorcycle business. One economic analyst has said that if the Japanese economy were actually to fail rather than just sputter as it is now doing, only one of the motorcycle makers would be sure to survive: Honda. This is not an agreeable prospect for planners at the Other Three.

There is no fanfare about going for Number One this timejust solid engineering and sales success

They don’t need Sun Tzu to tell them that attack is the best defense. When Japan’s current economic problems hit, Yamaha was aiming its biggest guns at the cruiser market. Yes, this was the company that had brought us the countless RDs, RZs and FZs-all part of a great sporting tradition. “Trash that file!” Yamaha seemed to be saying. “Shazam! We’ve become your cruiser company. Doncha love this bitchin’ Royal Star?” After betting the store on this strategy, Yamaha planners were surely dismayed by the V-Four’s limited success. Things looked bad. What next?

For me, the first sign of Yamaha’s return to mental health was the appearance of Mr. Iio (competition manager) at Daytona with a big roadrace team in 1997. His presence indicated that the company had decided to return to its long-established business and customer base: sports motorcycling. Insiders were saying Yamaha had turned into a 9-to-5 operation. Maybe, but now they were awake, beginning to burn the midnight oil as they had in the 1960s.

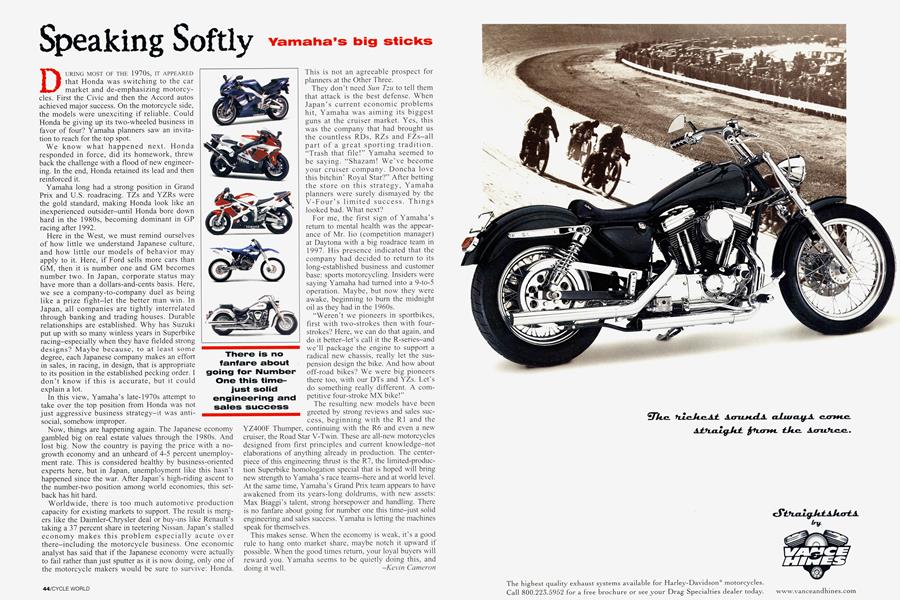

“Weren’t we pioneers in sportbikes, first with two-strokes then with fourstrokes? Here, we can do that again, and do it better-let’s call it the R-series-and we’ll package the engine to support a radical new chassis, really let the suspension design the bike. And how about off-road bikes? We were big pioneers there too, with our DTs and YZs. Let’s do something really different. A competitive four-stroke MX bike!”

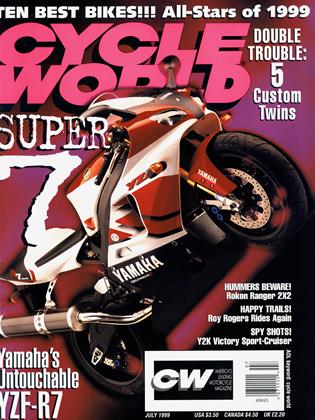

The resulting new models have been greeted by strong reviews and sales success, beginning with the R1 and the YZ400F Thumper, continuing with the R6 and even a new cruiser, the Road Star V-Twin. These are all-new motorcycles designed from first principles and current knowledge-not elaborations of anything already in production. The centerpiece of this engineering thrust is the R7, the limited-production Superbike homologation special that is hoped will bring new strength to Yamaha’s race teams-here and at world level. At the same time, Yamaha’s Grand Prix team appears to have awakened from its years-long doldrums, with new assets: Max Biaggi’s talent, strong horsepower and handling. There is no fanfare about going for number one this time-just solid engineering and sales success. Yamaha is letting the machines speak for themselves.

This makes sense. When the economy is weak, it’s a good rule to hang onto market share, maybe notch it upward if possible. When the good times return, your loyal buyers will reward you. Yamaha seems to be quietly doing this, and doing it well.

Kevin Cameron

View Full Issue

View Full Issue