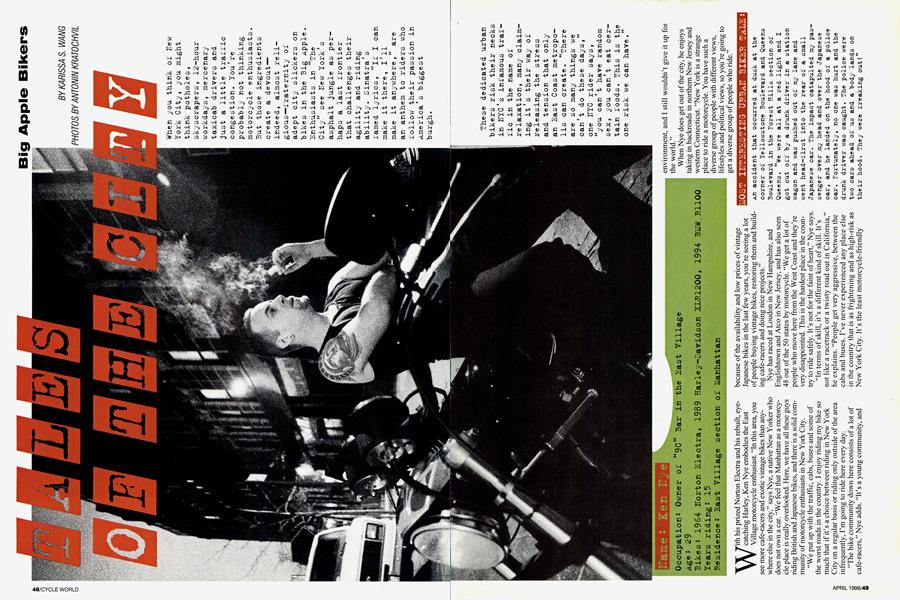

TALES OF THE CITY

When you think of New York City, you might think potholes, skyscrapers, 12-hour workdays, mercenary taxicab drivers and just a little traffic congestion. You're probably not thinking motorcycle enthusiasts. But those ingredients create a devoutindeed, almost religious-fraternity of adept city slickers on bikes in the Big Apple. Enthusiasts in "The City" see New York's asphalt jungle as perhaps a last frontier that challenges their agility and riding ability. Sinatra's famed lyrics, "If I can make it there, I'll make it anywhere," are an anthem to riders who follow their passion in America's biggest burgh.

When you think of New York City, you might think potholes, skyscrapers, 12-hour workdays, mercenary taxicab drivers and just a little traffic congestion. You're probably not thinking motorcycle enthusiasts. But those ingredients create a devoutindeed, almost religious~lraternity of adept city slickers on bikes in the Big Apple. Enthusiasts in "The City" see New York's asphalt jungle as per haps a last frontier that challenges their agility and riding ability. Sinatra's lamed lyrics, "If I can make it there, I'll make it anywhere," are an anthem to riders who follow their passion in America's biggest burgh.

Big Apple Bikers

KARISSA S. WANG

These dedicated urban bikers risk their necks in NYC's in±~amous traCfic in the name of relaxation, many claim ing it's their way of releasing the stress and tension that only an East Coast metropo lis can create. "There are so many things we can't do these days," one NYC rider says, "you can't have random sex, you can't eat cer tain foods. This is the one risk we can have."

These dedicated urban bikers risk their necks in NYC's in±~amous traCfic in the name of relaxation, many claim ing it's their way of releasing the stress and tension that only an East Coast metropo lis can create. "There are so many things we can't do these days," one NYC rider says, "you can't have random sex, you can't eat cer tain foods. This is the one risk we can have."

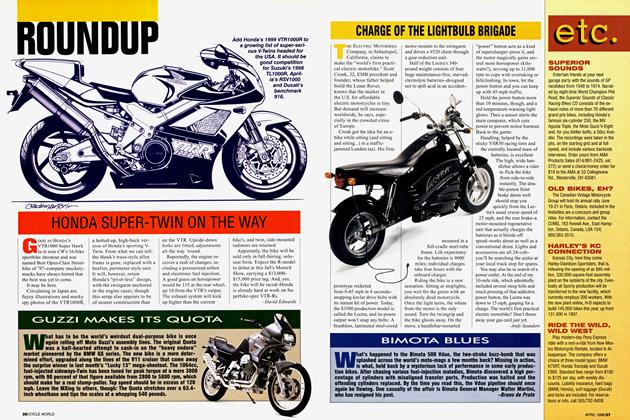

Occupation: Owner o1~ "9C" Bar in the East Village Age 29 Bikes 1964 Norton Electra, 1989 Harley~Davidson XLR1200, 1994 BL1W RllOO Years riding: 15 Residence East Village section o1~ Lianhattan

environment, and I still wouldn't give it up for the world." When Nye does get out of the city, he enjoys taking in backroads in northern New Jersey and western Connecticut. "New York is a strange place to ride a motorcycle. You have such a diverse group of people with different views, lifestyles and political views, so you're going to get a diverse group of people who ride."

With his prized Norton Electra and his rebuilt, eye catching Harley, Ken Nye embodies the East Village motorcycle enthusiast. "In this area, you

see more cafe-racers and exotic vintage bikes than any where else in the city," says Nye, a native New Yorker wh does not own a car. "We feel that Manhattan as a motorcy• cle place is really overlooked. Here, we have all these guy~ riding British and Japanese bikes, and there is a solid corn munity of motorcycle enthusiasts in New York City. "We put up with the traffic, cabs, buses and some of the worst roads in the country. I enjoy riding my bike so much that if it's a choice between riding in New York City on a regular basis or riding only outside of the area infrequently, I'm going to ride here every day.

"The bike community down here consists of a lot of cafe-racers," Nye adds. "It's a young community, and because of the availability and low prices of vintage Japanese bikes in the last few years, you're seeing a lot of people buying vintage bikes, restoring them and build ing cafe-racers and doing nice projects."

Nye has raced at Loudon in New Hampshire, and Englishtown and Atco in New Jersey, and has also seen 48 out of the 50 states by motorcycle. "We get a lot of people who move here from the West Coast and they're very disappointed. This is the hardest place in the coun try to ride safely. It's not for the faint of heart," Nye says.

"In terms of skill, it's a different kind of skill. It's not like a racetrack or a twisty road out in California," he explains. "People get very aggressive, between the cabs and buses. I've never experienced any place else in the country that is as frightening and as high-risk as New York City. It's the least motorcycle-friendly

LiO~T flTTEP~ESTING URBAN BIKER TALE:

n accident that occurred at dusk at the corner o±~ Yellowstone Boulevard and Queens Boulevard in the Forest Hills section o~ Queens. "We were all at a red light and I got cut off b~' a drunk driver in a station wagon and was pushed out of my lane and went head-first into the rear of a small Japanese car. The impact catapulted my pas senger over my head and over the Japanese car, and he landed on the hood of a police car. Fortunately, no one was hurt and the drunk driver was caught. The police were two cars ahead of us and a body lands on their hood. They were freaking out!"

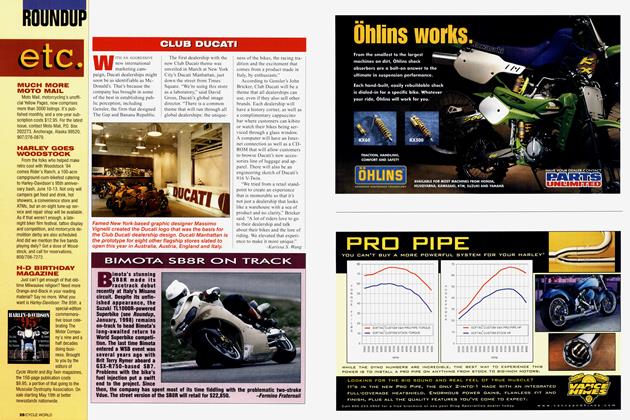

Cheryl Stewart is nicknamed New York City's "battery bolt fairy," and for good reason. Most bikers stuck on the side of the road are dumb founded when she rides up and assists them, not only with her knowledge of fixing bikes, but because she always car ries battery bolts in the pocket of her leather jacket. "People's battery bolts aren't tight enough and the bolts can walk out so the battery discharges," tipped over by a van outside her apart ment. With several witnesses, she is try ing to locate the culprit.

For her work as a sculptor/moldmaker for Broadway and opera pro ductions, Stewart relies on her bike to get to scene shops in places the sub way doesn't go, and her love of motorcycles extends to her loft and art studio. Visitors are greeted with her vintage bike calendar and at least 50 toy motorcycles, and a gyroscope sits handily on a shelf to demonstrate to guests the principal on which motor cycles operate.

"I'm not sure why I decided to learn to ride, but it was the best thing I ever did in my life," said the native New Yorker, who learned to ride in the Bay Area and then rode cross-country.

Although her trials in the city have netted her road rash, a broken wrist and a messed-up knee, she walked away from a fall that would give most urban riders nightmares. During a heavy rain storm, Stewart hydroplaned on the Brooklyn-Queens Expressway and went down, sliding behind the bike. "This car ran me over. I watched the car run over my right leg and I saw the bone flex. (It didn't break) so I walked away. I have angels watching over me. That was five bikes ago."

Stewart makes sure she regularly takes the Motorcycle Safety Foundation refresher course and, whether or not she can afford it, this summer she plans to take her fourth CLASS school at Loudon.

As a year-round motorcyclist, Stewart has ridden in the snow and slushy streets. "The coldest I've ridden is 8 Stewart said. "The roads here are so bumpy you have to think really differ ently about maintaining a motorcycle."

Stewart, who has gone through seven

bikes, is proud of her Honda Interceptor, on which she has amassed 50,000 miles. Another common prob lem riders face in NYC is bike damage while parked. After recently being painted periwinkle blue, her bike was degrees. The fishmongers who work here at the fish market helped me light fires under my locks to unfreeze them."

L1OST INTERESTflTG URBAI'~T BIKER TALE:

"There was a big Nor'easter about ±ive years ago. The water ate up South Street ax~d the West Side Highway. I lost my Tighthawk 700S arid Horida 0B650 .n the flood.

Name:cheryl stwart

o±~ Sirens T~Iotor or and 1982 Y~ Street Seaport

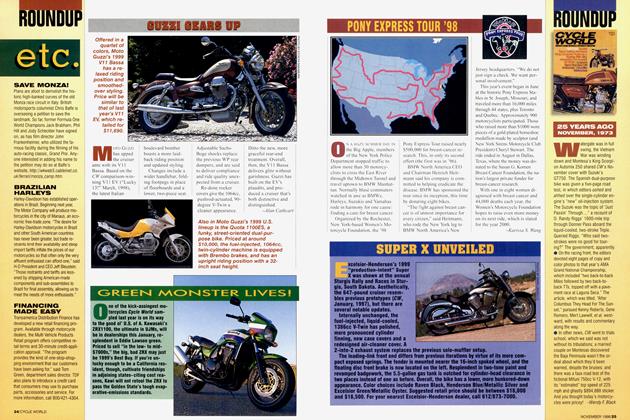

Born and raised in Brooklyn, Kevin Tobin commutes to his job at VH1 studios in the Hell's Kitchen section of Manhattan, where he oversees the technical aspects of television shows such as "The RuPaul Show," "Storytellers" and "Crossroads."

"We work in a dark studio, which sometimes is worse than working in a skyscraper," Tobin explains. "You have those days when you just need to clear your mind."

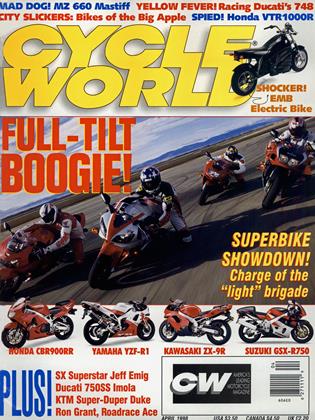

Drivers commuting to Manhattan through the congested Lincoln Tunnel can't help but notice Tobin's Coca-Cola red Ducati. "It's very dangerous in the city," Tobin admits. "Anything having to do with the morning rush hour anywhere in New York is dangerous. But it's worth it, just the freedom that you have."

As a motorcyclist commuting with thousands of cars, Tobin gets a close-up look at New York traf fic. "Before you get into New York, you have people reading the Wall Street Journal or New York Times in the car, or putting on makeup or talking on cellular phones.

"I'm finding new ways to be seen in traffic. Instead of an allblack jacket, I have one that is white with a red stripe. Only the shoulders are black. On my helmet I have red stripes and reflectors."

Besides trying to be seen, Tobin constantly confronts one of New York's most-infamous obstacles: potholes. "Manhattan is notorious for

Name:Kevin Tobin

Occupation' Ohiel Engineer at VHI Studios Age 29 Bike: 1996 Ducati 90055 C Years riding. 6 Residence. Bloomlield, r. hidden potholes," Tobin explains. "You can stand next to a pothole and swear that the ground is flat and the pothole is actual ly 6 inches deep. It's one of those things you have to deal with." ______

When the weather is warm, Tobin gets out on his bike

every weekend, even if it's only a short trip up the Hudson River. Along the way, he often hears compliments from bike-savvy New Yorkers. "Most of the time at stoplights, people admire the bike and ask me to rev it up so they can hear that Ducati sound."

L1OST flTTERESTII~TG URBi~1T BIKER TALE:

I~ the Lincoln Tunnel: "I ot stuck behind a commuter bus that had broken down. I had. to inhale exhaust ±umes until Port Authority police started re-directing trallie. ianhattan's air isn't reireshin~, but once you make a trip through the tunnel, it's the sweetest. You could swear `ou're smelling daisies compared to the air in the tunnel."

when moving to New York from Los Angeles to start his medical residency, Hossien Joukar was warned by friends not to bring his last bike, a Yamaha XT350. "I sold my bike cheap to my friend because everybody told me there was no parking here," Joukar says. A year

ring to the ER. "I guess we're adrenaline junkies. With the motorcycle, we don't know what's coming around the corner."

The one thing about Manhattan that Joukar is not used to is having his bike, which he parks on the street, tipped over. "People hit it and drop it. They try to park their car and they hit my bike, and every time that happens it costs me $150 to fix it," Joukar laments.

Joukar knows he is one of only a handful of ER residents in this city who are avid bikers. "You're sort of a family in emergency medicine. Once in a while we realize the other person rides, too, and we'll just sit and talk for hours."

Despite being fairly new to this city as a motorcyclist, Joukar wouldn't trade it for anything else. "The people here, cabs especially, drive like maniacs. In Los Angeles, they drive by rules-they sig nal, they drive in lanes. I like riding here."

ago, Joukar bought his fifth bike, a bright yellow Honda Hawk GT650. A motorcyclist going into emergen cy medicine might seem like a para dox, but Joukar thinks it makes sense. "It's exciting. You really don't know what's coming through the door, and that makes it fun," Joukar says, refer-

MOST INTERESTING URBAN BIKER TALE:

"About a year ago, I dealt with a serious motorcycle accident in the ER. A 25-year-old rider came into the trauma slot. He had a broken leg-exposed bone called an open

tib-±ib ±~racture. Two days later, I saw him and his leg had pins in it. Re said that when he got better, he d ride again. It showed me that nothing can stop us from rid ing, because I would do the same.

Name:Hossien Joukar

Occupation: Emergency medicine resident at Bellevue Hospital Center/New York University Liedical Center Sage: 33 Bike 1989 Honda Hawk GT650 Years riding: 21 Residence: Liurra~~ Hill section o~ Manhattan

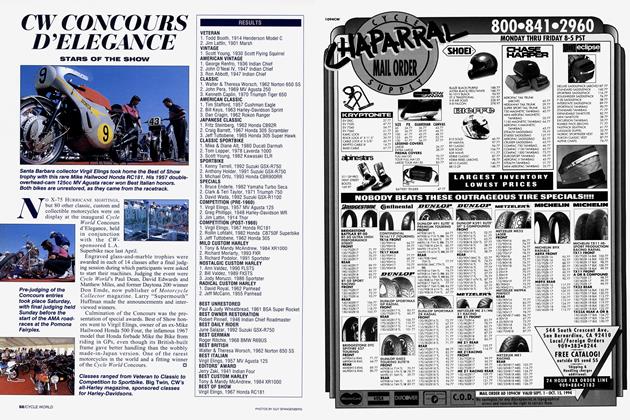

regg Pasquarelli swears by his -vintage BMW, and as an archi tect who appreciates fine design, he even evangelizes the company, "The design on these machines is incredible." Despite owning a car, Pasquarelli relies on his bike to quickly commute to work sites in the five boroughs of New York City. "It cuts my commute time in half It's cheap, I get 70 miles to the gallon, and I can park it anywhere," he said. "It's quick and carefree, and I only use Windex to keep it up."

A native New Yorker, Pasquarelli said he's noticed more motorcyclists on the streets in recent years. "In Italy and France, you see professionals in Armani suits riding all the time," he said. "In Italy, there are 30 bikes at a stoplight. New York is the European city in America, and it's finally coming to fruition here. In the dense urban envi ronment, the car is too much baggage and the motorcycle rules."

Urban riding has also infused an appreciation of the city, its skyscrapers and the streets that are lined in a grid pattern for commuters. "You get a com pletely different perspective of the buildings and the spaces of the city," Pasquarelli says. "Your understanding of New York changes from a grid to one of complete fluidity because of the way you move through when you're unencumbered by a car.

"Driving in New York is not about lanes, it's all about position and flow," he continued. "It's much closer to the fast break in basketball than it is to driv ing in other cities because it's not about being in a lane and having signs tell you when to exit, it's all about sprinting to the front of the line and boxing out the other person. You just have to think of it

as a video game and it's so enjoyable. And you know who your enemies are-they're painted yellow," he said, referring to cabs.

MOST INTERETING URBAN TALE:

A few years a~o when Pasquarelli wanted to sell his early 1970s Honda CB400, he didn't want anyone ca11in~ his apartment. Instead, he posted signs all over the East Village, reading, "Buy a burnt-out tenement motorcy cle, minimum price $250. Bring cash to the corner 0± Prince and Liott Streets on Friday at 7 p.m." - -

About 20 people showed up, Pasquarelli said, "And I had an auction. It took 3-and-ahail minutes and the bike sold for $700 to a very sexy German woman. Everyone used to make fun of that bike when I drove it, and this fall I read in New York magazine that the new bikes people are going alter are the old Japanese ones. They fill a void between the old beefy machines and a Vespa."

Name:Gregg Pasquarelli

Occupation Arc~ Age 31 Bike 1976 BL1W R60/6 Years ridin~ 8 Residence SoHo secti

View Full Issue

View Full Issue