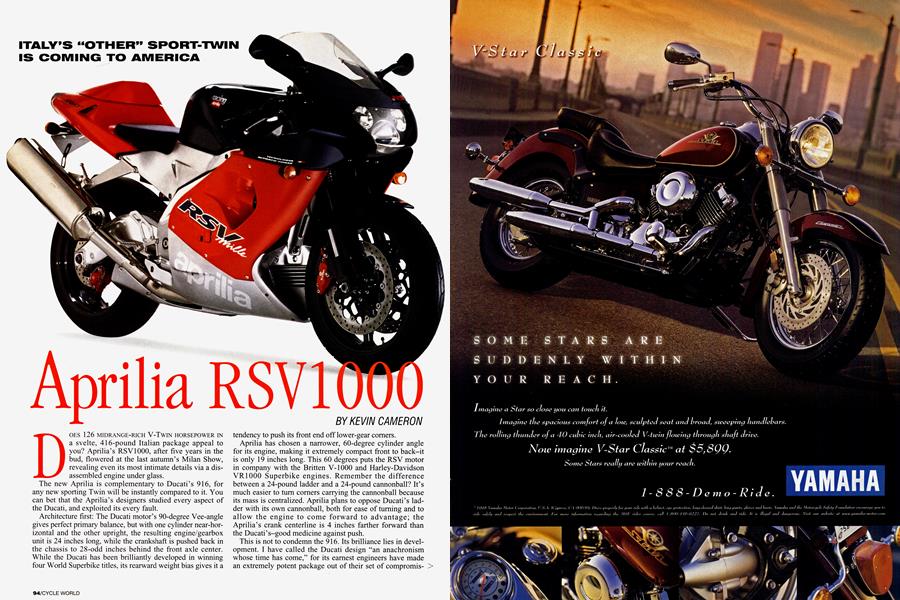

Aprilia RSV1000

ITALY’S “OTHER” SPORT-TWIN IS COMING TO AMERICA

KEVIN CAMERON

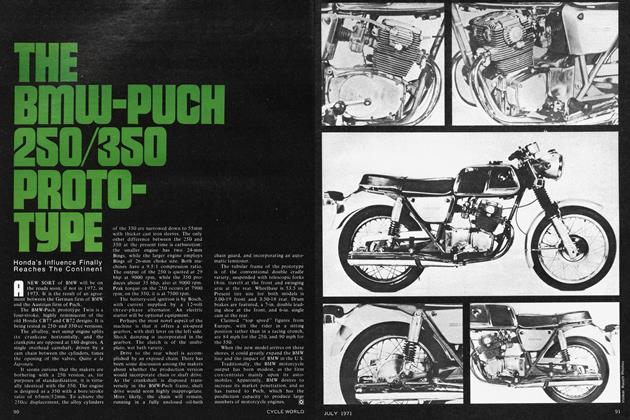

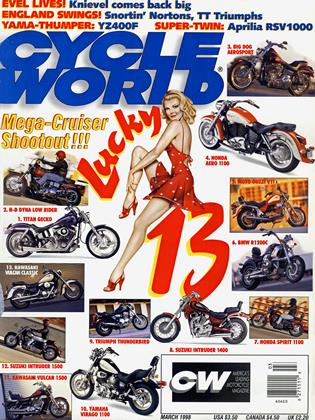

DOES 126 MIDRANGE-RICH V-TWIN HORSEPOWER IN a svelte, 416-pound Italian package appeal to you? Aprilia’s RSV1000, after five years in the bud, flowered at the last autumn’s Milan Show, revealing even its most intimate details via a disassembled engine under glass.

The new Aprilia is complementary to Ducati’s 916, for any new sporting Twin will be instantly compared to it. You can bet that the Aprilia’s designers studied every aspect of the Ducati, and exploited its every fault.

Architecture first: The Ducati motor’s 90-degree Vee-angle gives perfect primary balance, but with one cylinder near-horizontal and the other upright, the resulting engine/gearbox unit is 24 inches long, while the crankshaft is pushed back in the chassis to 28-odd inches behind the front axle center. While the Ducati has been brilliantly developed in winning four World Superbike titles, its rearward weight bias gives it a

tendency to push its front end off lower-gear comers.

Aprilia has chosen a narrower, 60-degree cylinder angle for its engine, making it extremely compact front to back-it is only 19 inches long. This 60 degrees puts the RSV motor in company with the Britten V-1000 and Harley-Davidson VR1000 Superbike engines. Remember the difference between a 24-pound ladder and a 24-pound cannonball? It’s much easier to turn comers carrying the cannonball because its mass is centralized. Aprilia plans to oppose Ducati’s ladder with its own cannonball, both for ease of turning and to allow the engine to come forward to advantage; the Aprilia’s crank centerline is 4 inches farther forward than the Ducati’s-good medicine against push.

This is not to condemn the 916. Its brilliance lies in development. I have called the Ducati design “an anachronism whose time has come,” for its earnest engineers have made an extremely potent package out of their set of compromis> es. Aprilia’s engineers, by starting without these particular compromises, mean to do better. It's a case of cashing in where your credit is good. The Japanese Fours do make their power through rpm, but are less good at delivering it off the bottom, in the all-important offcorner acceleration mode. Street riders most enjoy wide-range, torque-everywhere engines, and tend to reject shrieking revvers that feel gutless down low. Both are good reasons to build a V-Twin with a strong midrange, whether for street or racing. The bike with the best off-the-corner jump puts all other machines at a disadvantage. If there is a long straight, a bike with superior top-end power may overtake, but most World Superbike tracks don't make this easy to do. Engines with extreme bore/stroke ratios are weak in midrange, and here is why. If you pack on enough compres sion to make midrange, the resulting combustion chamber tends to be too tight to burn well at high revs. Or, if you reduce compression to give more room for good high-rpm combustion, away goes your bottom end. But as the stroke is made longer and the bore smaller, combustion-chamber shape improves, becoming taller and less wide, better able to retain enough turbulence to provide fast burning, even at a high compression ratio. As an historical example, in 1980 American Honda built three 1025cc four-cylinder test engines, each with a different bore/stroke ratio. The smaller the bore, the less spark lead was necessary, indicating quicker combustion in the taller, smaller-diameter combustion chambers. Thus, Twin builders have opted for unfashionably long strokes. The intake system begins with a “dynamic” airbox, meaning a resonant pressure-boosting system. It occupies the front half of the fuel tank, where twin vertical intake stacks lead air to 51mm fuel-injection throttle bodies (probably Hitachi) with butterfly throttles. Engine lubrication is dry sump, diverging from the long Italian tradition of deep, underengine, finned wet sumps. Compactness is the guiding principle. Oil is carried in an external tank, and is circulated by two pumps, one scavenge, one pressure. A single large-vol> ume silencer is used, the stated reason being that weight per silencer volume is less for a single large canister than for a separate pair. Cooling is handled by a large curved radiator, with an oilcooler in the chin position.

Another useful difference is in swingarm length. The shorter the swingarm, the greater the leverage that enginegenerated chain-tension forces have over suspension, potentially creating problems in suspension set-up. Ducati’s swingarm, thanks to its long engine, is just over 18 inches long. Aprilia’s is 21. Note that today’s massively powerful 500cc GP bikes have swingarms whose lengths approach half their wheelbase. Ducati cannot, with the existing engine, achieve Aprilia’s chassis figures.

Some will ask, “Does the world need another Twin?” But that is like asking, after the F4 Phantom, why the world needed another twin-engined jet fighter. The F4 was a classic

design, but awareness of its faults has been an essential key to subse-

quent designs such as the F-14. Sport-Twins are hot now, with Suzuki's redone TL1000R just appearing, and Honda's VTR1000 going into its second year-both use 90-degree engines. Some consider the Ducati definitive, and it is a beautiful and accomplished classic in its own time. But Aprilia's new bike represents five years of alternatives explored.

The RSV engine is Rotax-designed and manufactured, as other Aprilia engines have been, and has an oversquare 97 x 67.5mm bore and stroke. This may seem odd, since the clear trend in Japanese four-cylinder Superbike design is toward ever-shorter strokes as a means to make power at super-high rpm. Likewise, in Formula One auto engines, bore/stroke ratios have become extreme, close to 3:1 in recent designs, in the interest of reaching 16-17,000 rpm. A 1000cc Twin designed this way would measure an astonishing 124mm bore by 41mm stroke, and would peak at 15,000 revolutions. Motorcycle V-Twins haven't taken this direction; Ducati, starting with a 64mm stroke, went to 66, and the Harley VR, the Suzuki TL and Honda's VTR all have it as well. Now comes the Aprilia with its even longer 67.5mm. Why? Doesn't a longer stroke limit rpm, a prime path to high power?

Ducati’s racebike actually overdid midrange torque in the ’97 season. Its engine, built to the class’ displacement limit, delivered so much punch in the 7000-8000-rpm range that it was necessary to kill some torque by rpm-specific ignition retard and, perhaps, the use of additional flywheel weight. These big engines with reasonable bore/stroke ratios can really deliver the off-corner acceleration, and with its even longer stroke, Aprilia means to have its share.

Closing the throttle on a revving big four-stroke can hop or drag the back tire-something that was part of MV Agusta’s downfall in 500cc GP racing in the early 1970s. Aprilia’s innovative response to this is a vacuum-operated declutcher that reduces clutchspring pressure when intake vacuum appears. This, by allowing the clutch to slip, softens engine braking’s interference with handling during deceleration. As soon as you crack the throttle, full clutch torque capacity returns.

A 90-degree V-Twin like Ducati’s has zero primary vibration, but retains some fore-and-aft secondary (twice crank speed) shaking. But a 60degree Twin like Aprilia’s has substantial primary imbalance, equal to that of a Single. Conversely, it self-cancels secondary vibes. Harley reduces the primary shaking of its 60-degree VR1000 with a single first-order balance shaft, but Aprilia employs a pair of them, one below and ahead of the crank, one located between the cams atop the rear cylinder head. This is called AVDC, for “Anti-Vibration Double Countershaft.”

Power is stated as 128 crankshaft CV at 9250 rpm, with peak torque of 76 foot-pounds at 7000. This translates to 126 of our familiar SAE horsepower. With transmission losses and the assumption that there is no “Mediterranean correction factor,” this might yield 110-115 rear-wheel animals. We haven’t a proper set of third-party dyno curves for this engine yet, but as claimed torque falls only 2-3 percent between the torque and bhp peaks, and because they are widely separated (24 percent of peak rpm), it looks like nice flat torque. Just what the rider ordered.

Four-valve combustion chambers differ from the expected by having two sparkplugs each, similar to the 650 Single that Rotax makes for BMW. Conventional flat-topped, three-ring pistons are used. Camdrive is by chains.

The chassis is a modem twin-beam aluminum structure with bolted-on tailpiece. A 43mm inverted Showa fork carries the front Brembo rim, while a Boge damper controls swingarm motion through Aprilia’s own linkage. Braking is via a pair of the ubiquitous Brembo four-piston calipers at the front, acting on 12.6-inch discs. A single 8.7-inch with a two-piston caliper controls the rear.

Aprilia’s press release makes much of the aerodynamic qualities of the new

machine’s shape. With Italy’s long aeronautical history, there is no shortage of wind tunnels in which to test.

How will the market treat this machine, surrounded by rivals of like architecture? Exotic is our word for Italian machines. Their magnetic “otherness” generates intense interest even among non-motorcyclists.

Imagine that, for many Americans, this new Aprilia is love at first sight. It will then be up to Aprilia, ich has no dealer network here, to see that the pleasure of ownership-this love-lasts. Ducati neglected this aspect too long, and it is only now being corrected. As in marriage, exotic beauty is not enough. America is a 1-800 world; people want warranties cheerfully honored, all troubles handled and spare parts to be plentiful. It’s a tall order to create from nothing, but it must be done. Business analysts like to say that small corporations encounter a critical growth step at the $100-million-a-year level; below that, the creative enthusiasts who started the business can still cope; above it, big-corporation management techniques are increasingly imposed by sheer size and the expectations of capital markets. Aprilia is in this transition now, and I wish them luck.

An essential element in Italian Superbike appeal is racing success; it and commercial success are locked in endless symbiosis, neither able to exist without the other. Ducati’s faithful have delighted in Carl Fogarty’s triumphs over Japanese technology, as if yearning and intensity and deep red were magically superior to measurement and calculation. Aprilia management understands this and plans to race the RSV. How similar the racer will be to the Milan Show bike remains to be seen. To get competitive horsepower will require that every aspect of this design immediately march to the edge of the possible-and live there.

That may happen, but it won’t be cheap or quick. When Ducati began its racing crusade, World Superbike was much less sophisticated than today, and the 916 design has grown with the series. Aprilia’s race team must jump in at the deep end. Despite that, they have given themselves every advantage in chassis layout, and this will help them while they find the power and reliability required to cross swords with top WSB teams. Don’t forget that Aprilia engineers understand racing. Their small but highly effective team runs with a tough crowd in 250cc grand prix racing, where they have won three world titles against the likes of Yamaha and Honda. □

View Full Issue

View Full Issue

More From This Issue

-

Up Front

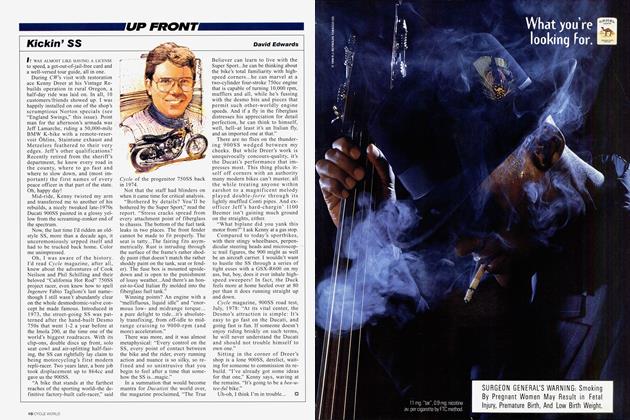

Up FrontKickin' Ss

March 1998 By David Edwards -

Leanings

LeaningsWinter Storage

March 1998 By Peter Egan -

TDC

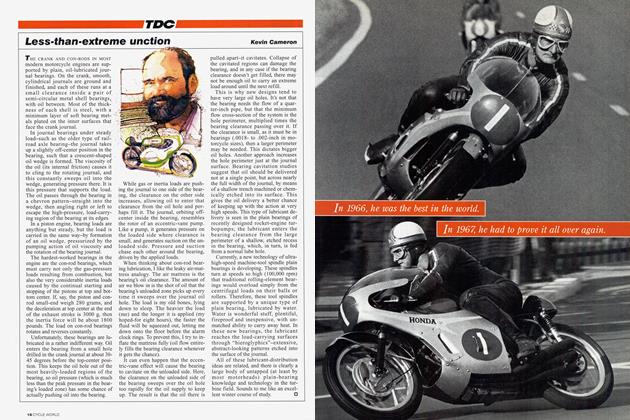

TDCLess-Than-Extreme Unction

March 1998 By Kevin Cameron -

Letters

LettersLetters

March 1998 -

Roundup

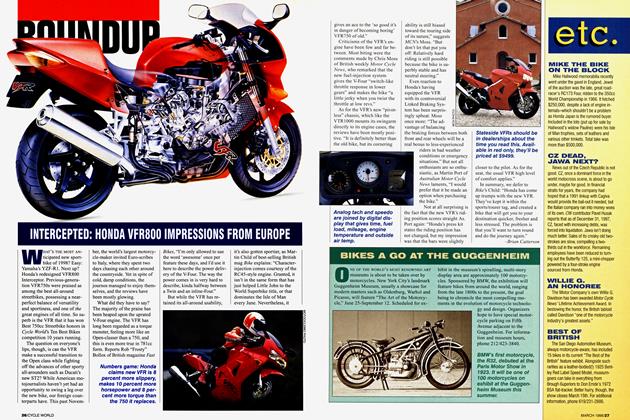

RoundupIntercepted: Honda Vfr800 Impressions From Europe

March 1998 By Brian Catterson -

Roundup

RoundupBikes A Go At the Guggenheim

March 1998