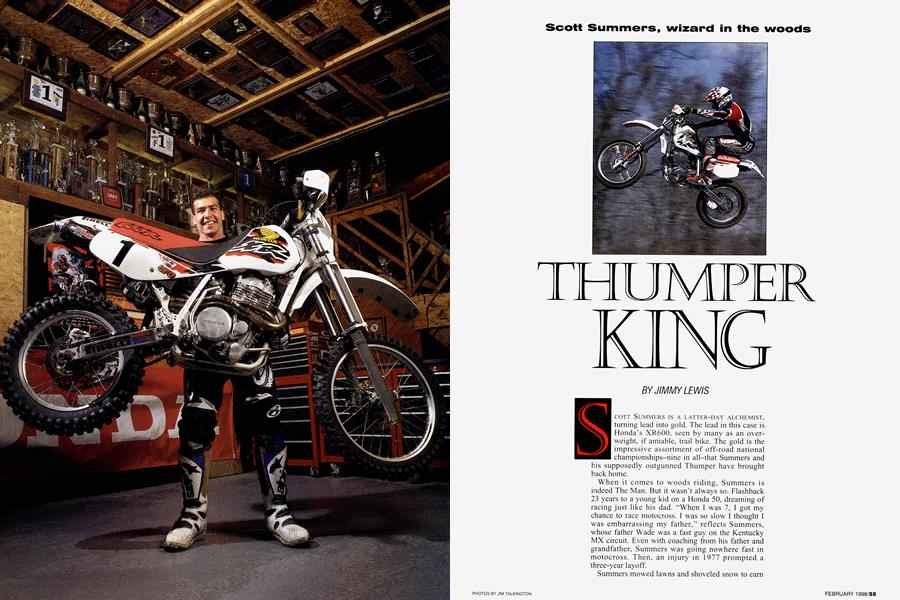

THUMPER KING

Scott Summers, wizard in the woods

JIMMY LEWIS

SCOTT SUMMERS IS A LATTER-DAY ALCHEMIST, turning lead into gold. The lead in this case is Honda’s XR600, seen by many as an overweight, if amiable, trail bike. The gold is the impressive assortment of off-road national championships—nine in all—that Summers and his supposedly outgunned Thumper have brought back home.

When it comes to woods riding, Summers is indeed The Man. But it wasn’t always so. Flashback 23 years to a young kid on a Honda 50, dreaming of racing just like his dad. “When I was 7, I got my chance to race motocross. I was so slow 1 thought I was embarrassing my father,” reflects Summers, whose father Wade was a fast guy on the Kentucky MX circuit. Even with coaching from his father and grandfather, Summers was going nowhere fast in motocross. Then, an injury in 1977 prompted a three-year layoff.

Summers mowed lawns and shoveled snow to earn enough money to buy a dilapidated Yamaha YZ100 that ended up costing more money than it was worth to keep running. “My parents saw how much I wanted to ride and they helped me out with an XR200,” he remembers. Moving to a 100-acre ranch in northern Kentucky gave Summers a place to ride. Hare scrambles racing was the next stepping stone. Local events gave way to regional races and soon after to nationals. The XR200 lasted a couple of years, and after flirtations with converted CR500 and CR250 motocrossers, Summers saddled up on the bike that would make him famous.

“I did a test with all of my bikes and found that when I rode an XR600, I used the least amount of energy and my lap times were faster, even though I felt slow,” he says.

In 1985, Summers and the big XR placed a respectable 11th overall in the National Hare Scrambles Series, running against the good ol’ boys club of HS regulars like Ed Lojak, Mark Hyde, John Martin and Kevin Brown. Summers kept plugging away, lowering his number and picking up sponsors each year. By 1989, friend Fred Bramblett, who owned a local Honda dealership, started helping with the wrenching chores. All the hard work paid off: Clinching the Number One plate in the ’89 Hare Scrambles Series put Summers on the map-and led to lots of questions from the established off-road community. How could some guy on an XR600 be winning races through the trees?

Pretty convincingly, is how. In 1990, Summers backed-up his performance with double championships in both the HS Series and the emerging Grand National Cross Country Series. Approached by most of the major dirtbike-makers, Summers could have gone “shopping” for a ride. But he was happiest on his hulking XR Thumper. Bramblett came on full-time, and Summers Racing was now a professional operation with a long list of sponsors. Summers and the XR continued thumping the competition: 1991, double championships again; 1992, GNCC champ; 1993, HS champ.

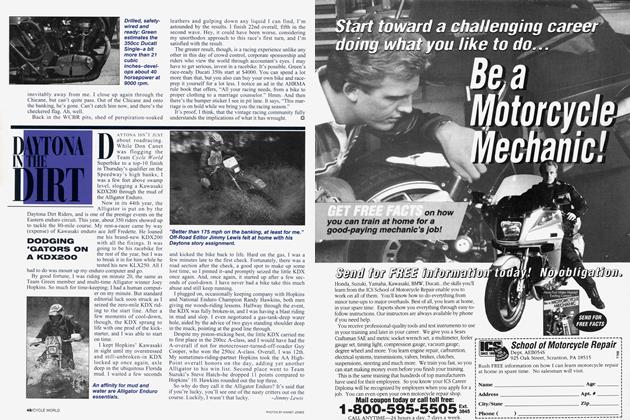

Slowly, other riders were taking notice; in fact, several defectors from motocross-Fred Andrews, Rodney Smith, Ty Davis and Guy Cooper-plus enduro champions Randy Hawkins and Steve Hatch, were soon chasing Summers through the woods. GNCCs, grueling three-hour races made up of tight trails, motocross courses, grass tracks and some two-track roads, became a prestige series; manufacturers started putting lots of effort into their cross-country teams. Summers bagged one more HS title in ’95, then GNCC titles in 1996 and ’97. Just how prestigious has the latter series become? Today, it isn’t uncommon to see factory box vans from KTM, Suzuki, Kawasaki, Honda and Yamaha along pit row. Moreover, reigning World Enduro Champion Paul Edmonson gave up defending his 1996 title overseas to add his name to a growing list of competitors on the GNCC circuit.

But still baffling is how Summers has taken an ordinary XR600, largely unchanged since its introduction in 1985, and put it to guys on lightweight two-stroke 250s. Summers just shrugs it off: “At first, people would laugh at me, but not anymore. I could take my old ’85 and still win a national,” he claims. “Most people have a misconception about horsepower and speed for this type of racing. You don’t look, feel or sound like you’re going fast (on a four-stroke), but you are.”

With respect to the nearly 300 pounds that makes up a raceready XR, Summers maintains, “The weight is an advantage. It hooks up and goes when everyone else is spinning.” Of course, you also have to take into account Summers’ extraordinary strength (witness his XR “clean and jerk” trick) and the huge amount of training he does. Then there’s Summers’ unorthodox riding style: handlebar cut down to just 28 inches to squeeze through the trees, arms tucked in and elbows down, sitting on the back of the seat even in turns. It’s a style that breaks every rule of proper dirtbike riding. And it’s a style that does not change when Summers pops out of the woods, a time when other riders flip back into motocross mode. Awkward looking, yes, but lethally effective.

What does the future hold for Summers? Right now, he and Bramblett are elbow-deep in SRC, Summers Racing Components, an aftermarket company started “as a result of a DNF,” says Summers. “It’s anti-DNF stuff (case savers, lever protectors, etc.) that I developed for the bike. People started asking me where they could get it.” Summers sees racing into his mid-30s, or as long as he is motivated to win.

Nine national championships don’t lie, putting Summers among an elite group of riders. “GNCCs and hare scrambles were thought of as second-rate motorcycle races ’til all these MX and enduro guys came over and didn’t instantly win,” notes Summers, obviously relishing the notion of beating the world’s best off-road riders on some plump playbike. “We’re doing three-hour motos through the trees, sometimes passing over 1000 guys and lapping up through 15th place. You have to be in excellent shape, as well as being able to ride real fast,” he says.

Scott Summers, quite possibly the world’s best XR600 salesman, has those bases covered.

View Full Issue

View Full Issue